Building a Lottery Game Smart Contract On the Juno Blockchain

Gelotto

Gelotto

My friend and I recently decided to build our first CosmWasm (CW) smart contract on Juno. It's a lottery game, called Gelotto — like the Italian word for ice cream. Ge-lotto.

The basic idea is simple: Create lotteries for a variety of IBC-enabled assets—JUNO, OSMO, ATOM, STARZ, etc.—running on different time frames. Some run hourly while others run daily. At the end of each game, the contract randomly selects a X% of players to win, where each player's odds are directly proportional to the number of tickets they have.

Objective

The goal of this article is to share how we've implemented our proof-of-concept smart contract so far, looking for feedback from the community. We're interested in finding partners and collaborators who are passionate and self-motivated, so please contact us on reddit or the #juno-lotto discord channel if you're interested.

Choosing Winners

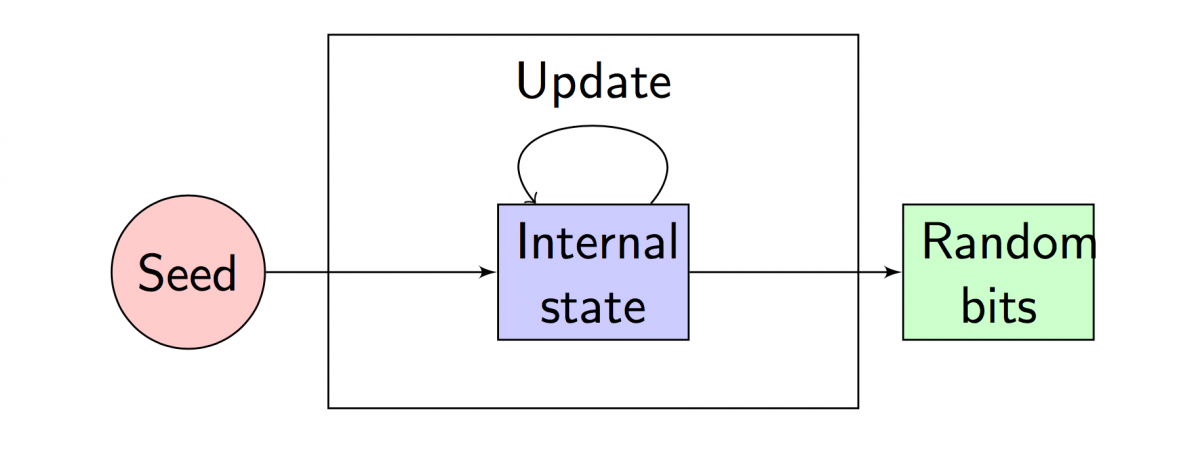

When a game ends, the contract needs to select winners in a way that is unpredictable yet deterministic. At the time of writing, neither blockhash nor block creation time are reliable sources of entropy in CW smart contracts. Those who need randomness must rely on oracles or other trusted parties. In the case of our prototype smart contract, we're attempting to use neither. Instead, our approach involves what I might describe as the accumulation of entropy over time. In particular, whenever a player places an order for tickets, the contract updates a "seed" value that it stores in state. At the end of the game, the contract feeds this seed into a random number generator—specifically, a PCG—which produces a deterministic sequence of random numbers that ultimately map to a set of winning players.

A generic pseudorandom number generator ⤴

Accumulating Entropy Over Time

When a contract is instantiated, it initializes the seed using a hash of various elements of game state combined with block metadata. Each time a player buys more tickets, the existing seed is combined and rehashed with new data to form a new seed, which replaces the old. This chain of hashing continues until someone executes an "end game" method in the contract that closes the game to new entries, updates the seed one last time, and sends it to the random number generator for selecting the winners.

Below is a sketch of the code that computes the initial, intermediate, and final iterations of the seed.

Seed Initialization

When the contract is instantiated...

use base64ct::{Base64, Encoding};

use cosmwasm_std::Addr;

use sha2::{Digest, Sha256};

pub fn init(

game_id: &String,

block_height: u64,

) -> String {

let mut sha256 = Sha256::new();

sha256.update(game_id.as_bytes());

sha256.update(block_height.to_le_bytes());

let hash = sha256.finalize();

Base64::encode_string(&hash)

}

Seed Update

When a player buys tickets...

pub fn update(

game: &Game,

player: &Addr,

ticket_count: u32,

block_height: u64,

) -> String {

let mut sha256 = Sha256::new();

sha256.update(game.seed.as_bytes());

sha256.update(player.as_bytes());

sha256.update(ticket_count.to_le_bytes());

sha256.update(block_height.to_le_bytes());

let hash = sha256.finalize();

Base64::encode_string(&hash)

}

Seed Finalization

When someone ends the game...

pub fn finalize(

game: &Game,

sender: &Addr,

block_height: u64,

) -> String {

let mut sha256 = Sha256::new();

sha256.update(game.seed.as_bytes());

sha256.update(sender.as_bytes());

sha256.update(block_height.to_le_bytes());

let hash = sha256.finalize();

Base64::encode_string(&hash)

}

Fast Roulette Wheel Selection

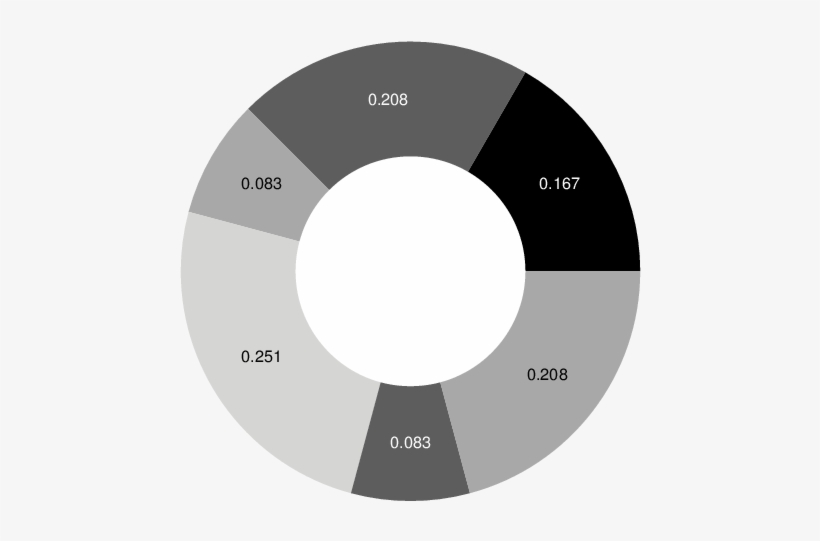

Winners are chosen at random based on their odds, which depend on the number of tickets they have. We use roulette wheel selection to perform this job. The name of the algorithm derives from the fact that selecting a winner is akin to a game of roulette, where a wheel with many segments is spun in one direction while a marble is inserted and circles around in the opposite direction. As the marble looses momentum, it falls into one of the segments of the wheel. In our case, each player's odds corresponds to a segment of the wheel. Likewise, the size of the segment corresponds with the number of tickets they have. The more tickets, the greater the size.

Example of probabilities in the form of a wheel ⤴

Note that a naive implementation of this algorithm is O(N), where N is the number of ticket orders received. Clearly, this is not ideal for a smart contract where gas fees apply, especially when there are potentially many thousands of orders to search through. Fortunately, there is another way, which is O(log N), and this is what we have done.

Data Structures

The contract's state must be structured in a way that is optimized for the sake of performing roulette wheel selection in O(log N) time. To this end, we store each distinct ticket order in the order in which they are received, consisting of the player's address, the the number of tickets ordered, and the cumulative number of tickets ordered so far, including the current. This looks something like:

struct TicketOrder {

owner: Addr, // player's address

count: u16, // number of tickets ordered

cum_count: u64, // cumulative count

}

From the count and cum_count (cumulative count), we can calculate the limits of each order's interval (i.e. their segment of the roulette wheel). Here's an example of a game with three orders from two distinct players:

TicketOrder | owner | count | cum_count |

| 0 | A | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | B | 10 | 11 |

| 2 | A | 4 | 15 |

The intervals for the above three rows would be: [0, 1), [1, 10), and [10, 15), respectively.

The Algorithm

To find each winner, the contract generate a random number between 0 and the total number of tickets sold. Call this number x. It's the "marble" in the game of roulette. In the above example, the total number of tickets sold is 15. Once we have x, the contract performs a binary search to find the TicketOrder that contains it. This process is repeated for each winner.

Here is some Rust code showing how a select_winner function could be implemented:

fn select_winner(

orders: &Vec<TicketOrder>, // full vec of ticket orders

n: usize, // number of winners to find

rng: &mut Pcg64 // random number generator

) -> usize {

let n_tickets_sold = orders[orders.len() - 1].cum_count;

let x = rng.next_u64() % n_tickets_sold;

bisect(&orders[..], orders.len(), x)

}

/// Perform binary search using bisection to determine which

/// TicketOrder's interval contains `x`.

fn bisect(

orders: &[TicketOrder], // slice of TicketOrders to search

n: usize, // length of slice

x: u64 // random value

) -> usize {

let i = n / 2;

let order = &orders[i];

let lower = order.cum_count - order.count as u64;

let upper = order.cum_count;

if x < lower {

// go left

return bisect(&orders[..i], i, x);

} else if x >= upper {

// go right

return bisect(&orders[i..], n - i, x);

}

i // return the index of the TicketOrder

}

Conclusion

Let us know what you think. Are we insane or are we at least headed in a good direction? How can we improve it, make it more secure, less predictable, more random, etc? I hope you found this article interesting (or at least entertaining). Thanks for reading!

-Dan

Subscribe to my newsletter

Read articles from Gelotto directly inside your inbox. Subscribe to the newsletter, and don't miss out.

Written by