TinyGo Channels on the Pico

Charath Ranganathan

Charath Ranganathan

In this tutorial, we look at how goroutines can communicate with one another using what are called "channels".

Objective

One of our earlier tutorials covered GoRoutines, which are one of the most common concurrency primitives in TinyGo (and Go).

Let us create a program which allows two goroutines to communicate. The main goroutine should send a message to another goroutine (we'll call it blinkGreen) with a random number of times to blink an LED. That goroutine blinks that LED that many times, and then returns a random number to the main goroutine, which proceeds to flash another LED that many times.

It is a very simple program that illustrates how messages can be easily passed between two goroutines.

Circuit

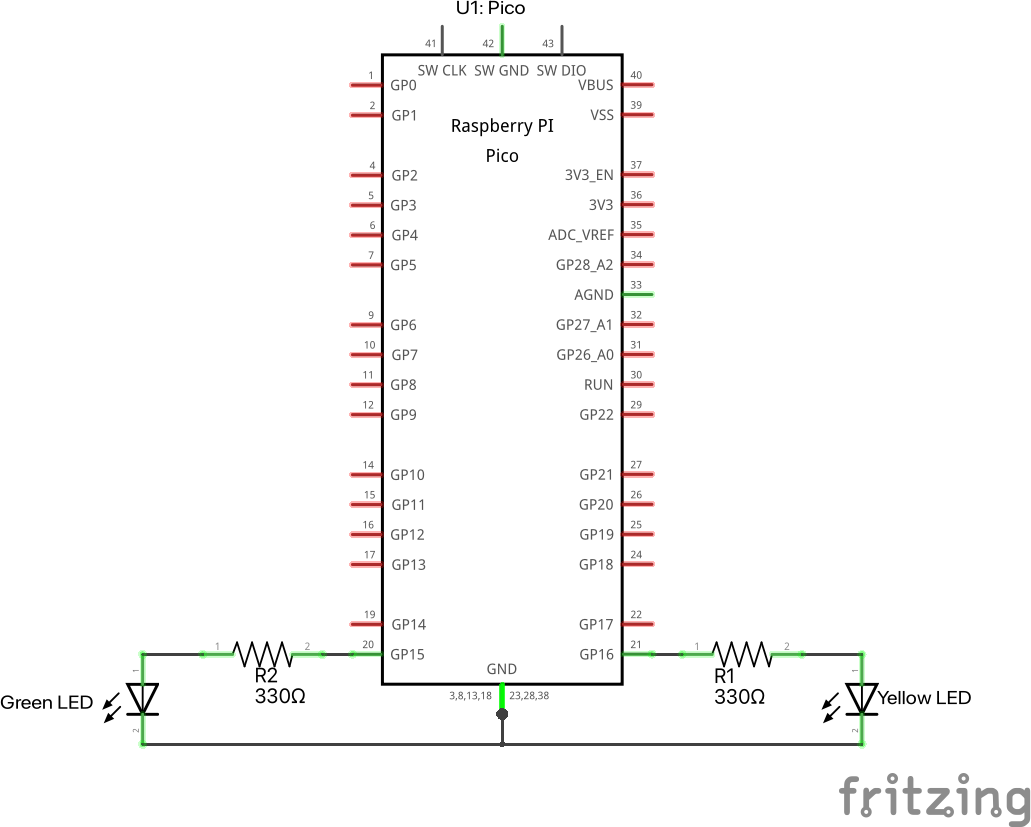

The circuit diagram below shows the necessary connections. A more detailed explanation of the circuit diagram appears below the image.

For this circuit, we connect one LED between GPIO16 and GND through a current-limiting 330 ohm resistor. The other LED is connected between GPIO15 and GND with another 330 ohm resistor.

The Program

The goal of our program is to allow two goroutines to communicate with each other through a shared channel. The message that is passed between the goroutines is a randomly-generated int which instructs the goroutine on how many times to blink the LED associated with that goroutine.

A more detailed explanation of the key parts of the program appears below the code listing.

// channels.go

package main

import (

"machine"

"math/rand"

"time"

)

const (

yellowLed = machine.GP16

greenLed = machine.GP15

)

func configure() {

yellowLed.Configure(machine.PinConfig{Mode: machine.PinOutput})

greenLed.Configure(machine.PinConfig{Mode: machine.PinOutput})

}

// Blinks an LED twice a second for a specified number of times.

func blink(p machine.Pin, n int) {

for i := 0; i < n; i++ {

p.High()

time.Sleep(250 * time.Millisecond)

p.Low()

time.Sleep(250 * time.Millisecond)

}

}

// This goroutine blinks the green LED `numBlinks` times, where

// numBlinks is specified by the message it receives via the channel.

func blinkGreen(c chan int) {

for {

// block until you receive a value via the channel

numBlinks := <-c

// then, blink the green LED that many times

blink(greenLed, numBlinks)

// return a random value to the `main` goroutine so that it blinks

// the yellow LED as many times as this random value.

numBlinks = rand.Intn(5-1) + 1

c <- numBlinks

}

}

func main() {

// Create an unbuffered channel of ints.

c := make(chan int)

// Initialize the random seed

rand.Seed(time.Now().UnixNano())

// Generate a random number between 1 and 5

n := rand.Intn(5-1) + 1

configure()

// Start the blinkGreen goroutine

go blinkGreen(c)

for {

// First blink the yellow LED `n` times

blink(yellowLed, n)

// then, generate a random number between 1 and 5

n = rand.Intn(5-1) + 1

// send that random number via the channel to `blinkGreen`

// so that it blinks the green LED that many times

c <- n

// wait for `blinkGreen` to return a random number to you

n = <-c

} // and repeat indefinitely

}

In the main function, we first create a channel of type int. Channels can transmit many Go types such as ints, strings, bools, and structs. In this case, we choose an int.

c := make(chan int)

The channel is unbuffered because we don't specify a second argument to the make keyword.

If we had specified a second argument to make, the channel would be a buffered channel with a capacity equal to that second argument. For example,

c := make(chan int, 5)

would create a buffered channel of ints with a capacity of 5.

Creating an unbuffered channel forces any goroutines that receive the values from that channel to block until a value is received via the channel. This is a nice way for us to pause execution of a goroutine until we signal it to start running via a message that we pass to it.

We then start up the blinkGreen goroutine which blinks the green LED. The number of times that it blinks the green LED depends on the value it receives via the channel, c.

The following line in blinkGreen blocks until a message is received via the channel. The syntax <-c indicates that numBlinks is being assigned the value out of the channel. The easiest way to figure out the syntax is to note the direction of the arrow. In this case, the arrow originates in the channel (as evidenced by where its tail starts).

numBlinks := <-c

Once the message is received, the blinkGreen goroutine is unblocked. It, then, blinks the green LED numBlinks times.

blink(greenLed, numBlinks)

Finally, the goroutine generates a random integer between 1 and 5 and sends that back to the main goroutine via the same channel.

numBlinks = rand.Intn(5-1) + 1

c <- numBlinks

Notice how in line 42, the channel receives the value because the arrow originates in numBlinks and terminates in the channel.

While all this has been going on, the main goroutine waits for a message back on the channel.

n = <-c

When it receives the random number from the channel (which was sent from blinkGreen in line 42), the main goroutine is unblocked and blinks the yellow LED n times.

This sequence repeats indefinitely.

Testing the Program

Wire up the circuit as shown in the diagram above. Then, flash the program to your pico:

% tinygo flash -target=pico channels.go

You will notice that the yellow LED blinks a certain number of times, followed by the green LED, and over and over again. The number of times each LED blinks is random.

Summary

In this tutorial we learnt how to use Go channels as a mechanism for communication between goroutines.

Subscribe to my newsletter

Read articles from Charath Ranganathan directly inside your inbox. Subscribe to the newsletter, and don't miss out.

Written by

Charath Ranganathan

Charath Ranganathan

I am an electrical engineer by training, and a software developer and manager by profession. I started coding after middle school (in the late 1980s) on a Sinclair ZX Spectrum home computer. As this is my personal blog, I focus on my hobby interests, i.e. microcontrollers, embedded systems, and electronics.