PyPy,Python and performance benchmarking

Pavel Durov

Pavel Durov

In this article, I will cover my experience with the PyPy that I was only recently exposed to. This article complements the Writing an Interpreter with PyPy tutorial from 2011 [1]. When I first tried to follow the steps of this blog post, I encountered many issues, such as out-of-date documentation, out-of-date code references, python version incompatibility etc. I will try to cover the gotchas and my learning experience here.

Writing an Interpreter with PyPy is about creating a BF [2] interpreter and the translation process of it with the PyPy toolchain. When I followed along, the main issues for me were related to the toolchain itself. Hence I decided to centre my attention on it here. We will not cover the BF interpreter here since it's all explained in the original blog post, but I will go through the PyPy toolchain and some basic benchmarking concepts essential for understanding the topic.

What exactly is PyPy 🤔

If you tried Python before, you were probably running CPython [3]. CPython is the most common implementation of Python VM (Virtual Machine). PyPy [4] is an alternative to CPython. With PyPy, we write our programs in RPython [5], and apply the RPython translation toolchain that generates binary executable. One major advantage of PyPy over CPython is speed which will be demonstrated later in this article using the basic benchmarking tool.

Jargon summary:

CPython — The most common Python implementation

PyPy — CPython alternative

RPython — restricted version of Python

Benchmark — the act of assessing program relative performance (time in our case)

Getting hands-on with RPython 👐

First, we need to write a simple RPython program, call it python_prime.py:

import os

import sys

def prime(n):

primes = []

for num in range(0, n):

if num > 1:

for i in range(2, num):

if (num % i) == 0:

break

else:

primes.append(num)

return primes

def write(s):

os.write(1, bytes(s))

def entry_point(argv):

num = int(argv[1])

primes = prime(num)

write('calculated primes: \n')

for p in primes:

write(str(p) + ' ')

return 0

def target(*args):

"""

"target" returns the entry point.

The translation process imports your module and looks for that name,

calls it, and the function object returned is where it starts the translation.

"""

return entry_point, None

if __name__ == '__main__':

entry_point(sys.argv)

It definitely resembles Python 👀. That’s cause RPython is Restricted Python. We had to choose some kind of computational problem, so we went with a prime number sequence generator. The actual compute work is not the point here 🙂.

Our RPython program also has some PyPy hooks — a function called target (the comment should be self-explanatory).

Running the program 🏃

We will use the Python 2.7.18 version since I found incompatibility issues with higher versions. If you don’t have the 2.7 Python version installed, you can use of the tools such as pyenv [6] or conda [7].

Run our program:

$ python ./python_prime.py 10

We should get similar output to this:

Benchmarking 🏋️

Now when we have our program in our hands, we can do some benchmarking to understand its runtime performance. We will use a tool called hyperfine [8] for that.

Mac installation:

$ brew install hyperfine

Linux Debian Installation:

$ wget https://github.com/sharkdp/hyperfine/releases/download/v1.15.0/hyperfine_1.15.0_amd64.deb

$ sudo dpkg -i hyperfine_1.15.0_amd64.deb

Similarly to how we run our RPython program, we can run it through the hyperfine utility:

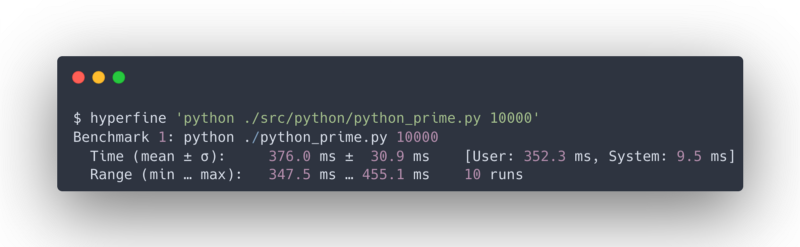

$ hyperfine 'python ./python_prime.py 10000'

Hyperfine runs our program ten times by default and gives us stats such as minimum and maximum execution times. We're not going to cover hyperfine in detail here; the important thing is to get a feel for it and a high-level understanding when comparing runtimes.

Generally, benchmarking results might be affected by different factors, such as the machine you run on, other processes that run simultaneously as you run benchmarking, hot vs cold starts, caching, etc. But, for our purpose, this benchmarking process we have here is good enough.

Translating our program using PyPy 🤓

The first step would be to get the PyPy source code:

$ wget https://downloads.python.org/pypy/pypy2.7-v7.3.9-src.tar.bz2

$ tar -xvf pypy2.7-v7.3.9-src.tar.bz2 # extracting

$ tar mv pypy2.7-v7.3.9-src ./pypy

Here we're downloading the source code, extracting it and renaming the extracted directory for later convenience. Once downloaded and extracted, run the PyPy translation toolchain:

$ export PYTHONPATH=${PWD}:${PWD}/pypy/

$ python ./pypy/rpython/translator/goal/translate.py python_prime.py

If you compare the tutorial code to mine, you will notice the difference in the file paths - translate.py was moved from pypy/translator/goal/translate.py to rpython/translator/goal/translate.py.

Also, I set the PYTHONPATH [9] environment variable to the current directory and the path to the PyPy source code. That would make the PyPy modules available for our program to run.

When running it, you should see toolchain logs on your terminal (it takes around 30 seconds on my M1 chip); when the process is complete, we should get the translated binary with the same name as the python file but with "-c" postfix.

$ ls -lah ./python_prime-c

-rwxr-xr-x 1 medium medium 217K 24 Sep 11:34 ./python_plain_class-c

Let's have a look inside 👀

$ file ./python_plain_class.py ./python_plain_class-c

python_plain_class.py: Python script text executable, ASCII text python_plain_class-c: Mach-O 64-bit executable x86_64

In case you don't trust the file command:

$ head ./python_plain_class-c

������ H__PAGEZEROx__TEXT__text__TEXT0/��0/�__stubs__TEXT��>��__stub_helper__TEXT�"��__cstring__TEXT2�q2�__const__TEXT�����__unwind_info__TEXTD��D�__eh_frame__TEXT8��...

Yep, it's indeed a binary file 🙂. Ok, so we translated Python using PyPy to a binary; now what?

Compare benchmarks 🔬

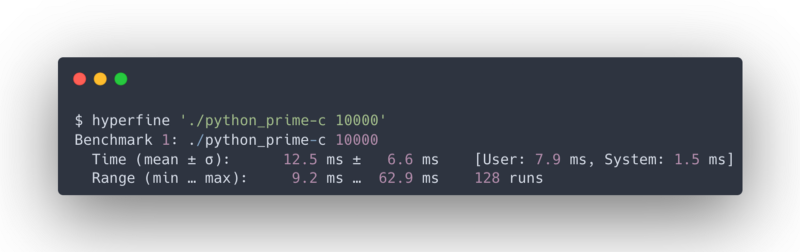

Run hyperfine on our translated program:

$ hyperfine './python_prime-c 10000'

Should get something like this output:

Spot the difference? We can also just run hyperfine to compare both programs:

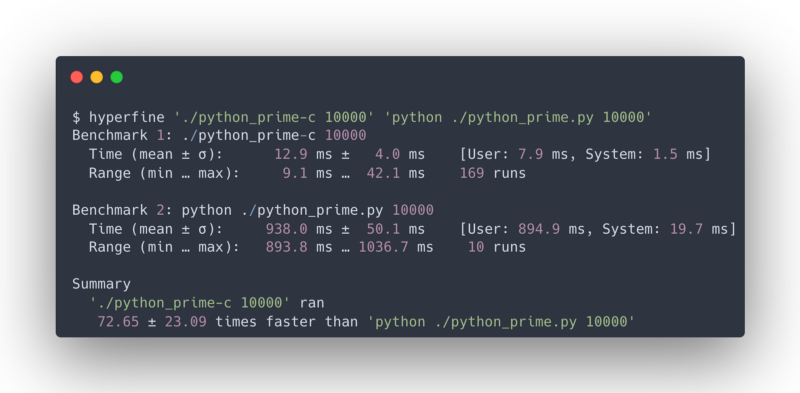

$ hyperfine './python_prime-c 10000' 'python ./python_prime.py 10000'

See full result:

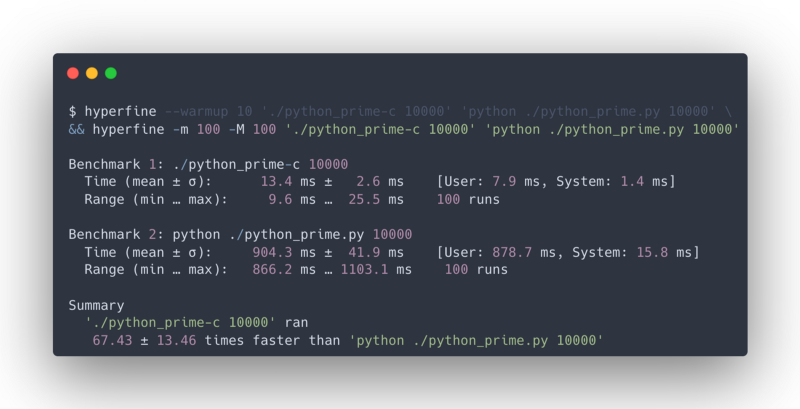

Say What!? 72 times faster 🤯?!

Well yeah, apparently 😶. Hyperfine won't lie to you. You can trust it☝️.

Did you actually expect that ?? Maybe I should have named this post - "Run your python programs X70 faster"? I think that's really cool… Ok, moving along 🙃.

Let's run hyperfine again, this time with worm-up and more runs:

$ hyperfine --warmup 10 './python_prime-c 10000' 'python ./python_prime.py 10000' \

&& hyperfine -m 100 -M 100 './python_prime-c 10000' 'python ./python_prime.py 10000'

We executed ten warmups before running the benchmark, then ran our programs 100 times each and recorded their execution times. The result is not far from the previous one; it's exactly the same metrics since the benchmark might have been skewed a bit as I'm not running it in a lab!

Summary ✏️

So what have we done? We built a simple RPython program, translated it using the PyPy toolchain, and witnessed substantial performance improvement with our eyes when comparing both program execution times side by side using hyperfine.

PyPy seems like a good choice for writing computational-intensive applications, especially if you want to stay in Python land. However, if you try it for a while, you will see that it might be less convenient than working with CPython; you might experience some obscure type annotation errors or unsupported function call exceptions. As with everything in life, it has its advantages and drawbacks.

I know, I know. Who cares about Python 2.7?! At the time of the article, we're already at Python 3.10.7. Why are we bothering with Python 2.7? It also reached the end of support cause you missed it!

The main reason is that I was following the article from 2011, and guess what? There was no Python version 3.10.7 in 2011. By the way, I bet you can use newer versions, as I've seen on the official download page. I just haven't tried them yet. I was excited when I heard about PyPy (almost a decade since I wrote my first Python language). Even if I'm not going to use it in production yet, just knowing that it's practically feasible to perform such optimisation is eye-opening.

What's Next ❓️

Next, we will look at PyPy jit trace logs and perform further optimisations now in our RPython applications.

References

[1] https://morepypy.blogspot.com/2011/04/tutorial-writing-interpreter-with-pypy.html

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brainfuck

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CPython

[4] https://www.pypy.org/

[5] https://doc.pypy.org/en/latest/coding-guide.html#restricted-python

[6] https://github.com/pyenv/pyenv

[7] https://docs.conda.io/projects/conda/en/latest

[8] https://github.com/sharkdp/hyperfine

[9] https://bic-berkeley.github.io/psych-214-fall-2016/using_pythonpath.html

Subscribe to my newsletter

Read articles from Pavel Durov directly inside your inbox. Subscribe to the newsletter, and don't miss out.

Written by

Pavel Durov

Pavel Durov

Human software engineer. My technical interests are Programming Languages, Open Source, Linux, Distributed Systems and Software Architecture. But you will probably find me doing other stuff most of the time.