A neat way to write algebraic data types in TypeScript using Proxies

Tom X Nguyen

Tom X Nguyen

If you have ever worked with reducers in React in the past, you may have noticed that best practices come with a lot of boilerplate. This article looks into why we use these practices, as well as introduces an ergonomic way to implement data types for any use case.

A quick look at Elm

A lot of the reducer patterns we take for granted today touches a lot on union/sum types in functional programming. If you look back at the prior art of Redux, you will notice that it is mostly inspired by Flux, but also from immutable and reactive libraries such as Immutable.js and RxJS respectively. One notable inspiration it mentions is from the Elm architecture, which takes some of Haskell's features of functional programming and applies it to their model, view, and update architecture.

In one of Elm's examples, quotes, you can see that it is a list of union/sum types with basic pattern matching:

type Model

= Failure

| Loading

| Success Quote

...

update : Msg -> Model -> (Model, Cmd Msg)

update msg model =

case msg of

MorePlease ->

(Loading, getRandomQuote)

GotQuote result ->

case result of

Ok quote ->

(Success quote, Cmd.none)

Err _ ->

(Failure, Cmd.none)

Modeling with algebraic data types

We often do something similar with React reducers. Take a look at the example code below.

const initialState = {

count: 0,

};

const reducer = (state, action) => {

switch (action.type) {

case 'INCREMENT':

return { count: state.count + 1 };

case 'DECREMENT':

return { count: state.count - 1 };

default:

return state;

}

};

// action creators

const increment = () => ({ type: "INCREMENT" });

const decrement = () => ({ type: "DECREMENT" });

console.log(increment()) // { type: "INCREMENT" }

console.log(decrement()) // { type: "DECREMENT" }

In this example, we've essentially created a data type for a counter, it being a union or sum type that takes in a type of INCREMENT and DECREMENT.

type CounterType =

| { type: "INCREMENT" }

| { type: "DECREMENT" };

We can't avoid the boilerplate that comes with creating these datatypes, but how it's structured makes it difficult for us to make it type-safe without explicitly labeling our action parameter.

Using proxies to achieve better ergonomics

What if we could write the counter type like this:

type CounterType =

| { type: "INCREMENT" }

| { type: "DECREMENT" };

const {

INCREMENT: increment,

DECREMENT: decrement,

} = createDataType<CounterType>();

Such that we can compose any arbitrary data type, given that we have label the generic with a strict union type from TypeScript. Surprisingly, you can do this with proxies.

Below is a data type constructor createDataType that uses proxies with TypeScript that takes in a string as a method name to return a constructor:

type DistributiveOmit<T, K extends keyof any> = T extends any ? Omit<T, K> : never;

type DataType<T> = T extends { type: keyof any } ? T['type'] : keyof any

function createDataType<T>(): {

[P in DataType<T>]: unknown extends T

? <D>(data?: D) => { type: keyof any } & D

: { type: DataType<T> } extends Required<T>

? () => T

: {} extends DistributiveOmit<T, 'type'>

? (data?: DistributiveOmit<T, 'type'>) => T

: (data: DistributiveOmit<T, 'type'>) => T

}

function createDataType(Shared?: new () => any) {

return new Proxy<any>(

(type: string) => (data = {}) => Object.assign(data, { type }),

{ get: (target, prop) => target(prop) },

);

}

We can then use this type constructor like this:

type CounterType =

| { type: "INCREMENT" }

| { type: "DECREMENT" };

const {

INCREMENT: increment,

DECREMENT: decrement,

} = createDataType<CounterType>();

console.log(increment()) // { type: "INCREMENT" }

console.log(decrement()) // { type: "DECREMENT" }

With this approach, we've removed the need to create action creators by composing the object directly as a function. Even if we do create action creators or value constructors, we don't need to compose the whole object from scratch or use constants to maintain data types.

But how does this work?

Destructuring the object like this makes it a bit confusing to read. Let's remove our object destructure and create our exotic proxy object:

type CounterType =

| { type: "INCREMENT" }

| { type: "DECREMENT" };

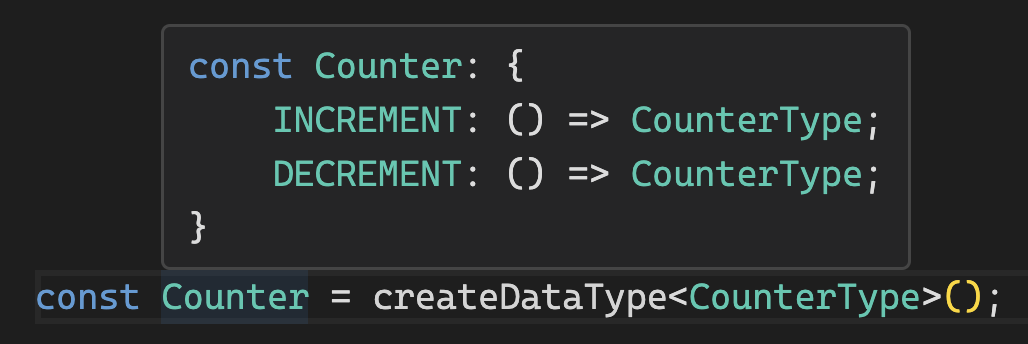

const Counter = createDataType<CounterType>(); // type constructor

This proxy object technically has no methods inside of it. But if we call a method like this:

const increment = () => Counter.INCREMENT();

What Counter.INCREMENT() does is create an object with the property type having a value matching the name of the method. This means the method name from the proxy is arbitrary, meaning you can write Counter.ARBITRARY() and it would be perfectly valid. This is where CounterType helps us in restricting the type names for the proxy:

So what does our Counter proxy object return as a type? It essentially returns a list of methods, matching the names of the strings we made from our CounterType:

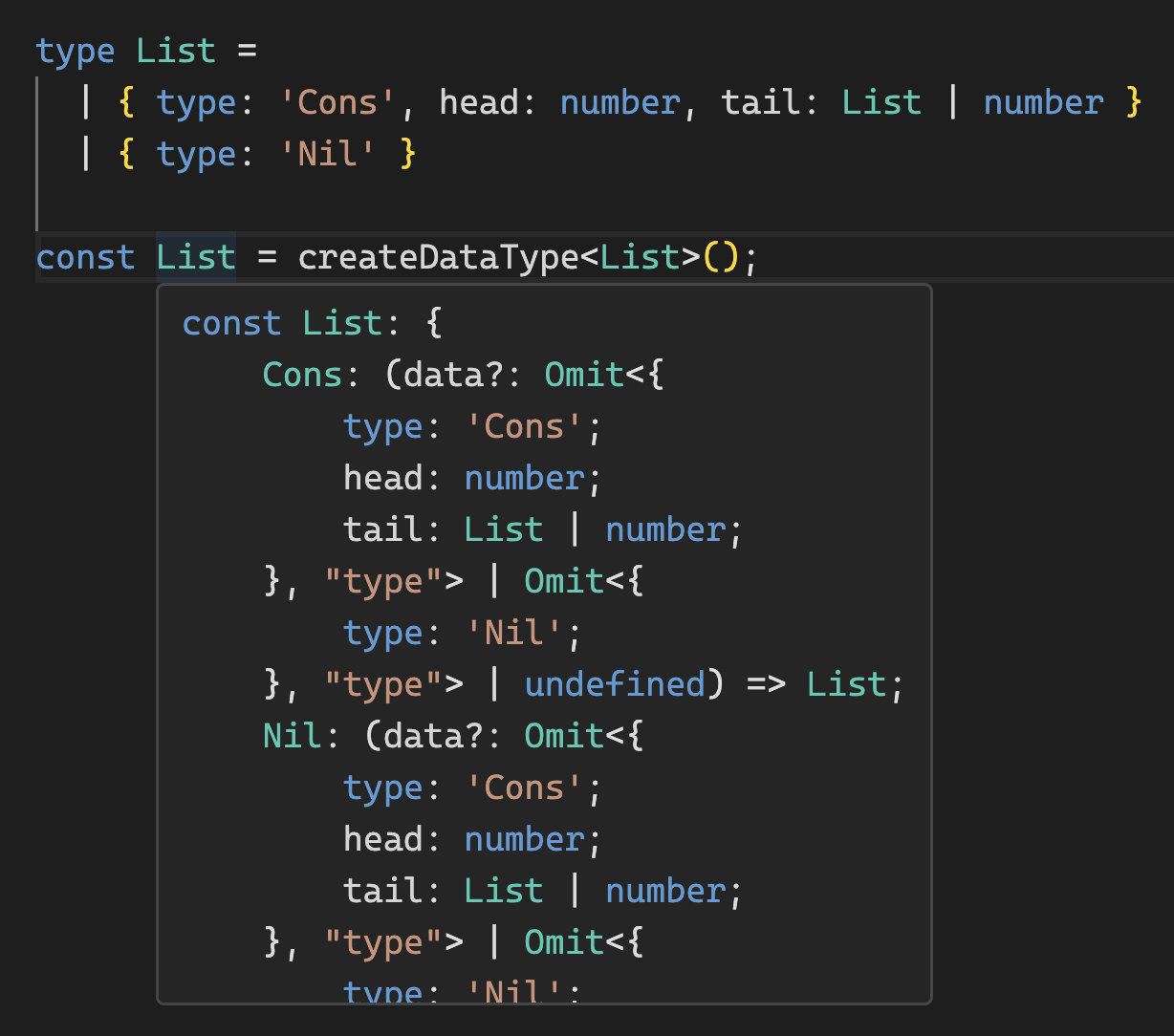

This way, we can easily compose more functional data types in a type-safe way with less boilerplate:

// You can create a singly linked list with less boilerplate

type ListType =

| { type: 'Cons', head: number, tail: List | number }

| { type: 'Nil' }

const List = createDataType<ListType>(); // type constructor

// value constructors

const Cons = (head: number, tail: List) => List.Cons({ head, tail });

const Nil = List.Nil();

const tx = Cons(1, Cons(2, Cons(3, Nil)));

/* {

"head": 1,

"tail": {

"head": 2,

"tail": {

"head": 3,

"tail": {

"type": "Nil"

},

"type": "Cons"

},

"type": "Cons"

},

"type": "Cons"

}

*/

// You can also compose the Option data type

type OptionType =

| { type: "Some", value: any }

| { type: "None" }

const Option = createDataType<OptionType>(); // type constructors

// value constructors

const None = Option.None();

const Some = some => Option(Some, {some});

None; // {Option: true, tag: "None"}

Some(5); // {Option: true, tag: "Some", some: 5}

Things to consider

Although this helps with ensuring general type-safety of data types composed with objects (as well as less boilerplate), it's not completely type-safe.

We can only guarantee that it is part of the union type that we declare in TypeScript, but it is currently not possible to pattern-match property keys to object values within a union type. Thus, it is possible to write something like this:

type List =

| { type: 'Cons', head: number, tail: List | number }

| { type: 'Nil' }

...

const Nil = List.Nil({ tail: 1 });

This is valid in TypeScript, even though we shouldn't expect a value for the type Nil. Maybe this will change when there is a way for TypeScript to do more granular pattern matching.

Conclusion

To conclude, we can use proxies to remove some of the boilerplate that comes with using reducers in React. A lot of these concepts come from Elm with functional programming concepts like union/sum types. Introducing an ergonomic way to implement data types using proxies in TypeScript helps reduces boilerplate and simplifies the creation of functional data types for various use cases.

Subscribe to my newsletter

Read articles from Tom X Nguyen directly inside your inbox. Subscribe to the newsletter, and don't miss out.

Written by

Tom X Nguyen

Tom X Nguyen

Started out this path from working with MIPS assembly at around 12 years old, and for some reason ended working mostly on fullstack.