Why we need techno-realism

Eric Torreborre

Eric Torreborre

Marc Andreessen recently wrote a "Techno-optimist manifesto". I promptly reacted that I was a techno-pessimist, that I was not believing in technology to be the solution. Even worse, I am tempted to say that more technology will be our demise.

The manifesto still made me think. We are faced with inextricable issues, and being pessimistic is not helping. What kind of message am I conveying, especially to my children, "Well, good luck because we're all doomed"? That's not fair to them or to anyone else. Why not be optimistic instead? After all, technology has already brought so many improvements in our lives, from low infant mortality to food in large quantities. There are incredible technological breakthroughs still to be conquered. For example, could there be new sources of carbon-free energy that we can exploit at a minimal cost for the environment? There are so many things we still don't know in the very fabric of our Universe, like how to unify Quantum Mechanics and the Theory of General Relativity. Let's discover them and rock our world!

Delusion of grandeur

Optimism is a much better position to solve problems because you start to postulate that solutions exist. On the other hand, what I don't want is to be delusional. That doesn't help. I cannot bet my future on the idea that anti-gravity devices will, one day, exist. The Techno-optimist Manifesto not only has a "can-do" attitude but also a "want-to" attitude. As if there was no reason for the Universe to not eventually grant all our wishes.

For example, we are very, very lucky, that on this planet, gravity is just low enough that loading a rocket with the best fuels we know of will allow it to go into orbit. Were the gravity slightly more important and the weight of the fuel itself would be too much for the rocket get to escape velocity! Maybe we are not meant to get much farther than our solar system. The closest star after the Sun is already very far away. Maybe we won't ever be able to visit it. There is no reason why we couldn't but there is also no reason why we could.

If we look at the history of science we can see many things that we cannot do:

There are limits to what we can prove with formal systems (Gödel's theorem)

There's no engine with perpetual motion (Laws of thermodynamics)

We cannot know the speed and position of a particle with equal precision (The Uncertainty Principle)

Nothing can travel faster than the speed of light

Those are some limits for how far we can go. This could still be a long way! Yet we first need to apply a critical eye to where we are now. This is where the word delusion comes to mind.

The Techno-optimist Manifesto makes a huge mistake, it forgets the materiality of technology. It sees technology as a final product, as a pure gain, devoid of any costs.

Smartphone, really?

The object representing the biggest technological prowess of our times is probably the Smartphone. It is indeed a smart combination of materials research, hardware design, and manufacturing processes.

I remember sincerely dreaming about such a product as a kid. Something that I could use to call my friends, read, listen to music, watch videos, all in one object.

But let's come back to the physical object. What is it made of? What did it take to produce this marvel of technology? Short answer:

Making this object was incredibly destructive to our planet and some fellow humans

It is most likely destined to go to landfill and be wasted forever

Some resources it consumed can never be reclaimed

We need to enjoy those phones now because there's no guarantee that our successors will be able to do the same. Not very smart.

Minerals and metals

In this post, I want to highlight how much our technology relies on some very concrete reality. Reality is messy. Messy and worrying since we are planning on increasing technology in our lives.

Let's just focus on minerals and metals. Without metals, there is no technology. We cannot make our beloved smartphones or computers to run ChatGPT. We cannot even produce the energy to power those devices!

What about metals then? Where do they come from? Let's enter the wonderful world of mines.

Note: for what goes below I am relying on the various presentations and sources given by Aurore Stéphant, a French mining engineer and geologist.

What's in a mine?

The gold needle in the haystack

The first thing to understand is that there is nothing like a gold bar, or even nowadays a gold nugget, in the wild. If we want to collect gold, an amazing electrical conductor, we need to dig an enormous amount of land. There is only one gram of gold per 1 ton of ore. And when we go after that gram of gold we dig out many other metals:

Iron (30 to 66%)

Aluminium (25 to 30%)

Zinc (4 to 20%)

Uranium (1 to 3%)

Indium (100 g / t)

and many more

Some of those metals are harmful to our health. They end up disseminated in the environment when we mine for gold.

We don't have a gold bar yet, mining is just the first step.

Steps to purity

Three more steps are necessary, depicted here for copper:

concentration, mostly a physical operation to make a thin powder

extraction, a chemical or pyrometallurgy operation

refinement, via fire and electrolysis

All these operations require large amounts of energy, chemical products, and water.

This explains why the footprint necessary for mining operations is very large. We need to move heaven and earth to get reasonable amounts of purity! Let's have a look at some consequences.

The dirty secrets of mining

Mining sites are human disasters

In many places in the World, mining sites have been created and have expanded, to the detriment of the local population. In Romania, a large copper has used a small nearby valley as its dumping site. See, that was a village there in the 80's:

(photo taken in 2015, we can't almost see anything nowadays with 14000 tons dumped every year)

300 families have been moved out of the zone, with no compensation. Sadly, the mining and oil industries are responsible for the most number of murders, human violations and social/environmental conflicts in the World.

A mining site is irreversibly damaged

Even when there are attempts to "rehabilitate" a mining site, soil and water sources stay polluted for years. Worse, in some cases like uranium mines in France, the site has been made "invisible", so that everyone forgets there was a mine but the source of pollution stays.

The UK Environment Agency writes (in 2023):

Mining played a major part in Britain’s rich industrial history, but this also left thousands of abandoned mines scattered across our landscape. Almost all these mines had closed by the early 1900s but they are still releasing harmful metals including lead, cadmium and copper. This is one of the top 10 issues for water quality in England as it harms fish and river insects. […]. The worst river pollution by metals is caused by water flowing out of tunnels dug by miners. Rainfall also washes metals out of the millions of tonnes of highly contaminated wastes the miners left at the surface.

Not only those mines do not provide any more value today, but they are actively, and for a long time, harmful.

A mining site is dangerous

When a mine is active, all the residue goes to a "tailing dam":

In the last 10 years, there were from 3 to 7 tailing dam failures per year. The two largest ones were:

The Mariana Dam disaster, in 2015. It has been recognized as "the worst environmental disaster in Brazil's history". Entire fish populations were killed almost instantly, and the contamination went through the Rio Doce up to the Atlantic Ocean

The Brumadihno Dam disaster, 3 years later. It killed 270 persons, with a mud wave going at 120 km/h. Twelve million metric cubes of tailings were released and cadmium was found up to 302 km downstream of the mine site

It is only getting worse

It is getting worse for 2 reasons:

There is less

We want more

There is less

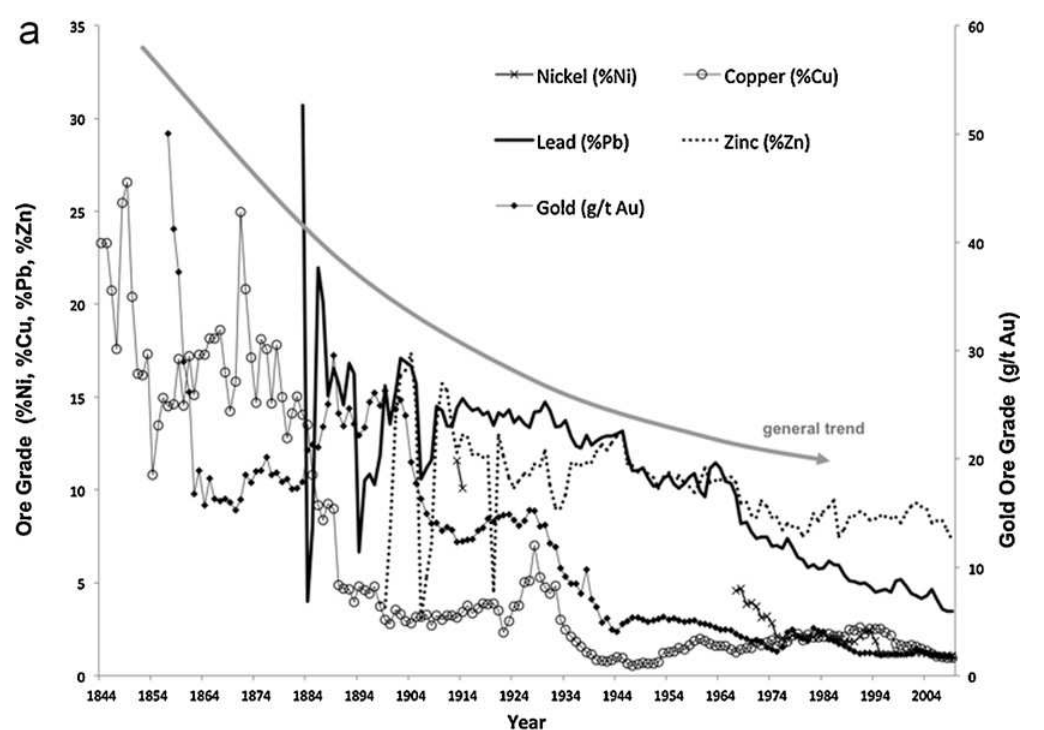

The good old mining days are over. The concentrations of all minerals are noticeably going down:

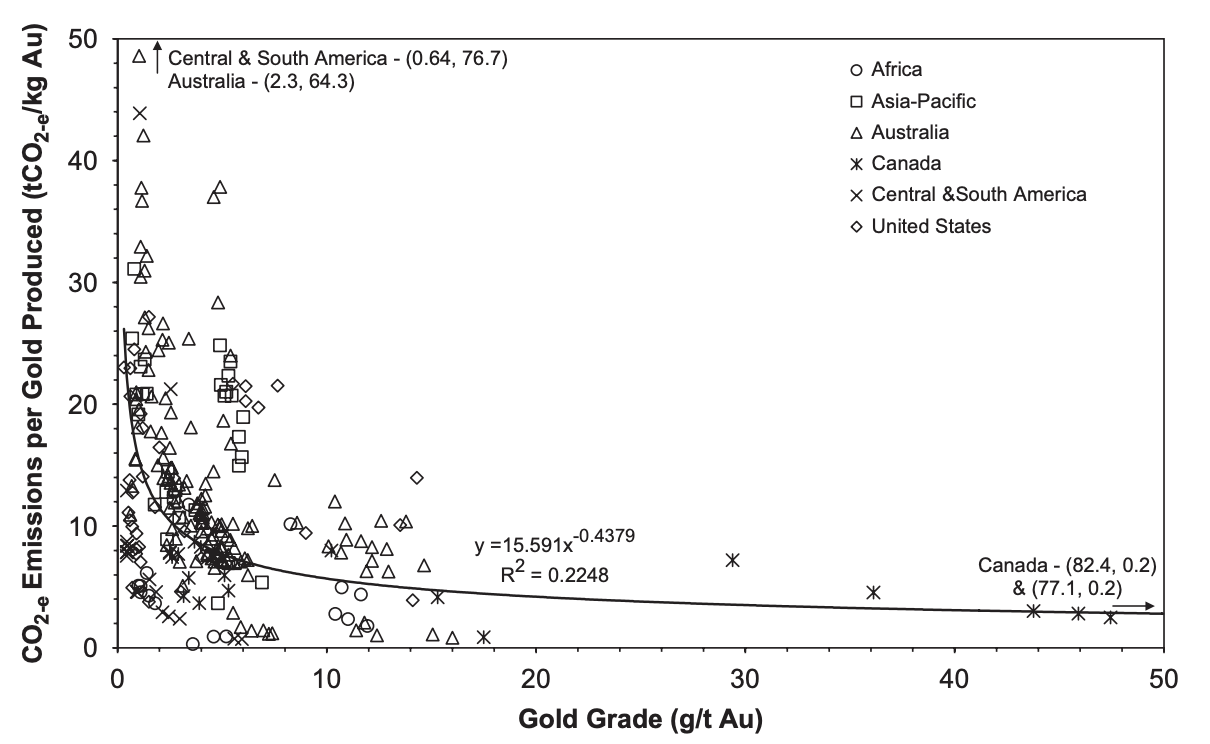

This means that, if we want to dig up the same quantities we need to move out a lot more soil, with a lot more energy, and environmental damage. This graph shows the correlation between the emitted CO2 and gold concentration for various mining sites around the world:

We have similar graphs for energy, water and cubic meters of moved land.

We want more

In our quest to fight climate change, we aim to transition to electric cars, electric trucks, electric foundries, and so on.

More quantities

The copper demand is expected to grow from 25 tons/year to 36 tons/year by 2031. We need around 20 kgs of copper in a conventional, and 80 kgs in an electric car. Some of that copper comes from recycling (8.7 million tons/year) but there are limits to what we can recycle:

Many products using copper are still in use

The last point is interesting, we need lots of energy to produce and distribute energy, which itself is needed for mining and recycling. What makes us think that we can eventually get even?

More qualities

Let's take an example where technology is improving things: LED lights. A LED lightbulb consumes 75% less energy than an incandescent lightbulb and lasts up to 5 times longer. That looks like a great technological win. But the downside is in the recycling. LED lightbulbs are more complex than incandescent lightbulbs. They involve more materials:

They are bonded together, often with glues and foams that make separation of them using mechanical processes very difficult. You’ve got all types of materials in there from plastics, glass, ceramics, aluminum, copper. You have PCBs. It’s a complete mixture. We have a problem that’s going to come back and bite us

(Nigel Harvey, CEO of UK Lamp recycler, in ledmagazine.com. Yes, there is a magazine for everything 😄).

At least LED lamps are useful.

Still optimistic, but realism won't hurt

We can still be optimistic. But we have to seriously revise our goals. The direction we are taking is simply not sustainable. Technological problems are multi-dimensional and we have become quite good at improving in some dimensions at the expense of other dimensions: our environment, our resources and our human population.

In many ways, we are acting like a 20-year-old who has inherited a large fortune and is squandering it. In 200 years we have burned a treasury that took millions of years to accumulate, without thinking about tomorrow.

It's a difficult multi-criteria optimization problem

That's why I'm opposed to the Techno-optimist manifesto. It is very one-sided. It implicitly promotes going faster in the same direction without looking at all the problems that technology is creating at the same time.

This way of thinking is reflected in the Manifesto section about markets:

We believe free markets are the most effective way to organize a technological economy. Willing buyer meets willing seller, a price is struck, both sides benefit from the exchange or it doesn’t happen. Profits are the incentive for producing supply that fulfills demand. Prices encode information about supply and demand

As if prices, a one-dimensional quantity, could encode everything there is to know in an exchange. This is very naive and blatantly false. When you buy a TV, a car, or a phone, are you only looking at the price? No, you are generally agonizing over a zillion of other criteria.

As a society, we need to start considering our technology in all its dimensions. Maybe that means not having a flashlight on our phone, but hey water is drinkable!

I still want to play with my toys too

What I am writing is not necessarily very popular amongst my fellow software engineers. I understand that. I love programming. Each year, we are coming up with new programming languages, new models of computations, and new ways to dice and slice data. But maybe it is time to rethink my toys, to rethink our toys. As much as I appreciate my smartphone, I did not have one for the first 10 years of my adult life. I still had a good life.

ChatGPT can summarize a piece of text in seconds. Fantastic. How much is it worth in terms of irreversibly polluted land? We need to start thinking about our technological products from start to finish. How many times did you hear in a conversation between software engineers "Data is cheap"? Or "I can easily spin off 100 machines to do this if I want to"? Are they wondering what that means at the end of the line?

Actual recommendations

What can we do then? Here are some recommendations from experts in the field:

Massively limit the amounts of metals used in products (favor recycled metal) and overall quantity (which means making fewer products).

De-digitalize society. Remove unnecessary screens, stop making gizmos (Alexa etc...), and have an equivalent non-digital usage for every digital usage. Yes, that means that eventually fewer people like me are needed 😔.

Educate people about the resource consumption of our products.

Design for recycling.

Plan and collect the requirements in terms of resources based on human fundamental needs: water, food, heat, health, and education.

This is where we need to be optimistic and innovative as humans. We need to believe that we can create a good life for ourselves, and the future generations, without burning everything to the ground.

Subscribe to my newsletter

Read articles from Eric Torreborre directly inside your inbox. Subscribe to the newsletter, and don't miss out.

Written by

Eric Torreborre

Eric Torreborre

Software engineer at the intersection of functional programming, product development and open-source