Learning Note: Getting Familiar with Memory

Raine

RaineThis article is a summary of Chapter 4 of:

Yazawa, H. (2015). 程序是怎么跑起来的[How Program Works] (L. Fengjun, Trans.). People's Posts and Telecommunications Press

The Physical Mechanism of Memory

The computer memory is composed of memory IC, including types like DRAM, SRAM, ROM, etc. RAM (Random Access Memory) can be both read and write, and includes sub-categories of Dynamic RAM (need to constantly refresh to store data) and Static RAM (no need to refresh to store data). ROM (Read Only Memory) can only be read.

Fig. 1

(Yazama, 2015, Fig 4-1, p63)

Fig 1 shows the pins of a memory IC. VCC and GND refer to power cord and ground electrode.

1 D0 to D7 are pins for digital signals representing the data being read/write. 8 pins can represent 8 places (1 byte) of data.

2 A0 to A9 are pins for address signal, which can represent addresses from 0000000000 - 1111111111 (1K) addresses. Thus, this memory IC has 1 KB memory. (Each address can store 1 byte, and there are 1024 addresses in total)

3 RD and WR are pins for control signals, in which RD indicates reading operations and WR indicates writing operations.

Fig. 2

(Yazama, 2015, Fig 4-2, p65)

In a writing operation, the WR signal is first set to 1 (indicating writing). The digital pins are set to the data to write and the address pins are set to the address to store the data. Fig 2 (a) represents writing data 11110000 to address 0101010101.

Similarly, in a reading operation, the RD signal is set to 1 (indicating reading). The address pins are set to the address to read the data. The values in the digital pin would represent the data read from the given address.

Variables and Pointers

The data types in programming languages are used to show the number of consecutive memory addresses needed to store the data. For example, char uses one memory address, short uses two memory address, and long uses 4 bytes (long generally uses 4 bytes on 32-bit systems and 8 bytes on 64-bit systems). The operating system decides the address of variables duing runtime.

Fig 3.

(Yazama, 2015, Fig 4-4, p68)

Pointer is another type of variable that stores a memory address rather than a value. In C, a pointer is defined by adding a * in front of the variable. For example,

char *d = 100 // define a pointer d of type char

short *e = 100 // define a pointer e of type short

long *f = 100 // define a pointer f of type long

In this case, all pointers point to the value at address 100. The pointer's data type specifies the number of consecutive bytes read from the address. Pointer d reads 1 byte (address 100). Pointer e reads 2 bytes (address 100 - 101), and pointer f reads 4 bytes (address 100 - 103)

Fig 3

(Yazama, 2015, Fig 4-5, p70)

Arrays

Array is a data structure consisting of consecutive memory addresses storage the same data type. The data in each address can be accessed through array indexing. As mentioned in Chapter one (https://raineyang.hashnode.dev/learning-notes-what-cpu-means-for-programmers), array indexing is implemented with the base register (storing the starting address) and index register (storing the array index) in CPU.

Stack, Queue, and Circular Buffer

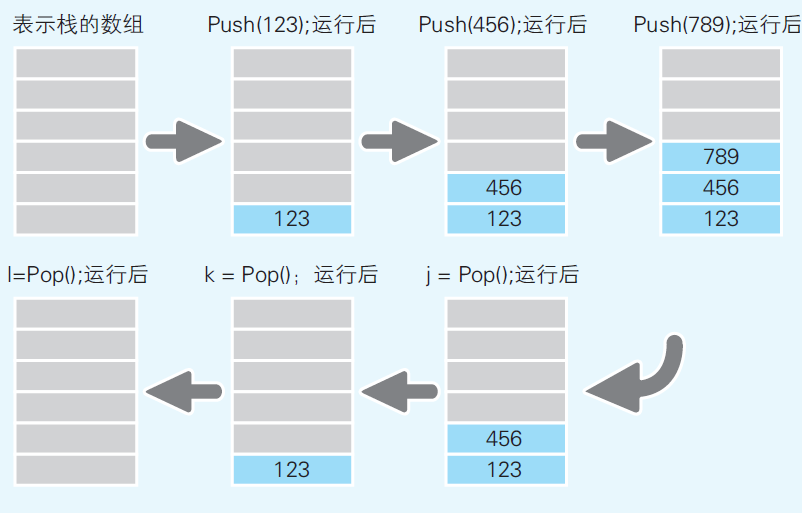

Stack and queue are both data structures that do not involve indexing, which simplifies the indexing problem in some cases. Stack reads and writes data in a last input first output order (LIFO) (Fig 4). Stack is convenient for cases when we want to store the data elsewhere and retrieve the data back in the same order.

Fig 4

(Yazama, 2015, Fig 4-7, p74)

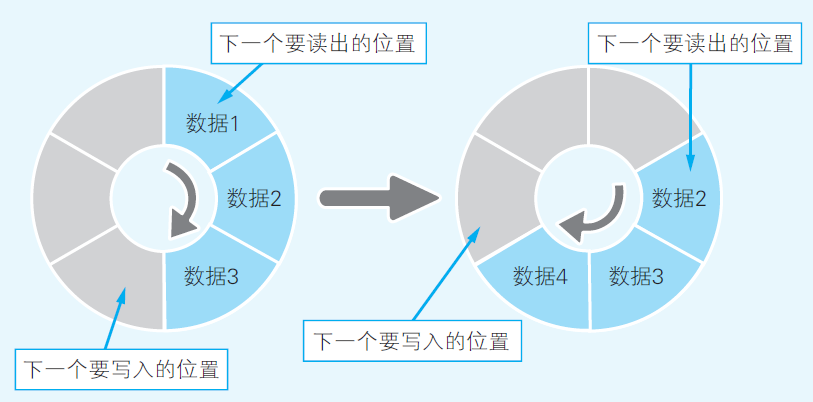

Queue reads and writes data in a first input first output order (FIFO) (Fig 5). Queue is useful in implementing a buffer for asychronized communications or receiving data from multiple programs.

Fig 5

(Yazama, 2015, Fig 4-8, p75)

Queues are usually implemented with circular buffer. A circular buffer contains an array and two pointers (a tail pointer pointing to the location for writing and a head pointer pointing to the location for reading). When a new elemented is enqueued/dequeued, the tail/head pointer increases by one, and wraps around to the begining when reaching the end of array. The circular buffer is considered full if the next position of tail pointer is not empty, and the buffer is empty if the head and tail pointers point to the same address. Circlar buffer allows for effect enqueue/dequeue operations for a queue.

Fig 6

(Yazama, 2015, Fig 4-9, 76)

LinkedList and Binary Search Tree

Linkedlist is a data structure that allows for efficient adding/removing elements. Each element in a linkedlist stores its value and the address of the next element in the linkedlist. The address stored in the last element is indicated by a invalid address such as -1.

Fig 7

(Yazama, 2015, Fig 4-10, p77)

Linkedlist is an efficient data structure for adding/removing elements compared with arrays. For linkedlist in Fig 7, if we want to remove the third element 333, we can simply change the "next address" stored in the previous element p[1] to its next address p[3]. In this way, even though the value in p[2] still exists, there is no pointer pointing to it, so it is "removed" from the linkedlist.

Fig 8

(Yazama, 2015, Fig 4-11, p78)

After the remove operation, if we now want to add a new element 777 to the 5th place in linkedlist. We can overwrite the previous discarded p[2] to be the new element, and make it the "next address" of the 4th element p[4]. Finally, we link its "next element" to p[5].

Fig 9

(Yazama, 2015, Fig 4-12, p78)

The advantage of these operations is that we do not need to shift other elements in the linkedlist. For arrays, since we must make all elements in a consecutive order, we must shift all elements after the one being added/removed. However, linkedlist does not support index searching like array. We have to start from the first elements, and find the next element based on address stored in the previous one to reach the element we are searching for, which takes a O(n) operation.

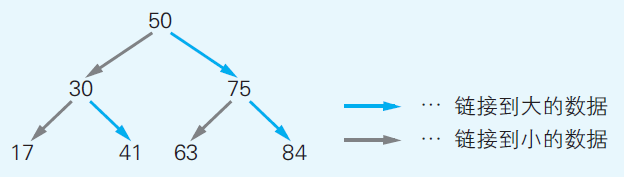

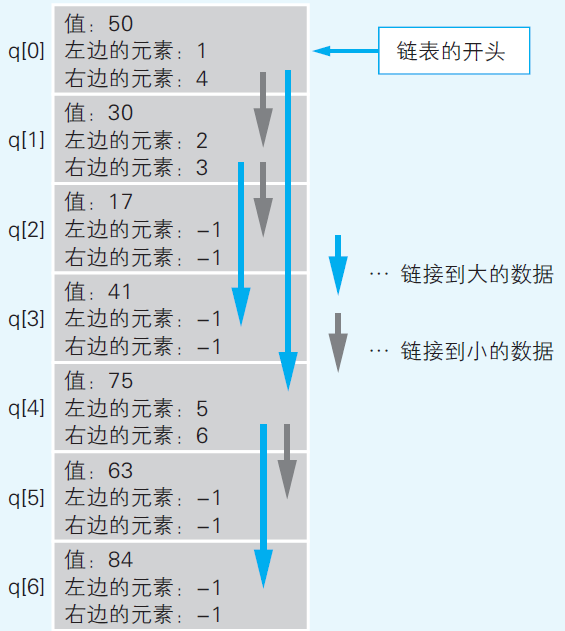

Binary search tree enhances more efficient searching operations. A binary search tree implemented by linkedlist stores addresses in each element, one pointing to a smaller value and the other pointing to a larger value.

Fig 10

(Yazama, 2015, Fig 4-15, p80)

Fig 11

(Yazama, 2015, Fig 4-16, p81)

Subscribe to my newsletter

Read articles from Raine directly inside your inbox. Subscribe to the newsletter, and don't miss out.

Written by