Go concurrency simplified. Part 1: Channels and goroutines

Mykola

Mykola

Christmas season is around the corner, that's why another evening I was standing in a long queue at the post office with some Xmas presents packed inside the box. The line moved pretty slowly, as there was only one postman for the whole crowd of customers. The guy was running back and forth, and I felt really sorry for him. Not sure why, either out of boredom or because of several long evenings I spent working on my open-source library for managing asynchronous pipelines, but my brain turned engineering mode on and tried to optimize the process of handling parcels.

Suppose we imagine the post office as an application. In that case, it becomes clear that we are dealing with the classical "consumer-producer" problem, where customers like me are producers (because we bring boxes, letters, etc.), and the postman is a consumer of all these. And it's pretty easy to see that the system bottleneck is that there is only one consumer for N producers.

So, how can we improve this? Shall we increase the amount of consumers? Or should we open more postal windows? A little bit of both? And how can we map this into the application and code after all? These are good questions, so let's try to answer them in this series of blog posts.

A step aside

Let's take a short break before diving deep into the technical topic and discuss the context for this series of blog posts. As you might have noticed from the post title, the main idea is to examine the concurrency in the Go programming language. And even though I'd love to jump into such powerful concepts like select statements, for loops with channels, WaitGroup, etc., this will be unfair to the readers who are not that familiar with Go but still would like to follow along to explore and learn the power and beauty of it. That's why we'll take it slowly here and start with the basics.

Wait a minute! Why the heck are we talking about Go in the first place? Well, this is a fair question. I promise you that my blog won't be only about any specific language, framework, or tool but rather about software engineering and tech in general. However, to discuss some topics/concepts, I'll need to pick a language or a tool to use, and I believe that this time Go is the right choice. Why? Google designed this language to be both powerful and simple, and while I wouldn't claim it to be the best language out there (I don't believe in the concept of "the best" at all, by the way), it is a good one to have in the toolbox - for instance, it's my language of choice for writing the CLI applications. Also, it has a clear syntax that should be easy to understand if you are familiar with any C-like language.

However, while Go is pretty straightforward, some parts of the language might not "click" from day 1. And concurrency is one of those. Therefore, I'll use real-life examples alongside the code to guide you all the way to the "aha" moment. Let's jump into it!

Back to the post office

Welcome back to the post office! The queue is still here, so the problem hasn't solved itself - surprise-surprise. But you know what - it's time to represent the situation we have with a code. Let's start with the models' definitions:

type Customer struct {

Name string

Item string

}

type Worker struct {

Name string

}

This and other code examples are available in this GitHub repo.

If you are new to Go and don't know what struct is

Struct is a Go way to represent user-defined types in the form of a collection of fields. Thinks of them as Java/Python/Kotlin/C#/many other languages classes. If the field name starts with the uppercase letter, the field is public, while the lowercase ones are private.

Let's add some actions that those actors can perform:

func (c *Customer) GiveAway() string {

item := c.Item

fmt.Printf("%s gives away %s\n", c.Name, item)

c.Item = ""

return item

}

func (w *Worker) Process(item string) {

fmt.Printf("Worker %s received %s\n", w.Name, item)

fmt.Printf("Worker %s started processing %s...\n", w.Name, item)

fmt.Printf("Worker %s processed %s\n", w.Name, item)

}

If you are new to Go and don't know what

(c *Customer)isIt's a Go way to say: "This function belongs to the Customer struct. Use

cto access a current instance of the struct within the function." In this context, think ofcas Java/Kotlin/C#thisor Pythonselfkeywords.

And now, it's time to combine all of this to recreate the post-office situation:

func main() {

bobWorker := Worker{Name: "Bob"}

zlatan := Customer{Name: "Zlatan", Item: "football"}

ben := Customer{Name: "Ben", Item: "box"}

jenny := Customer{Name: "Jenny", Item: "watermelon"}

eric := Customer{Name: "Eric", Item: "teddy bear"}

lisa := Customer{Name: "Lisa", Item: "basketball"}

queue := []Customer{lisa, eric, jenny, ben, zlatan}

for _, customer := range queue {

item := customer.GiveAway()

bobWorker.Process(item)

}

}

If you are new to Go and don't know what

[]CustomerisIt's a Go way to specify a slice of Customers. Thinks of slice as Java/Kotlin/C# ArrayList, Python list, or dynamic arrays in general.

If you are new to Go and don't know what

_isIt's a Go way to ignore the result of the function. Go compiler is pretty strict and throws a compilation error if there are unused variables within the codebase.

rangereturns two results: the current index and the current element of the slice. In this context, we don't need an index. That's why we use_to make the compiler happy.

If, after looking at this code, you find it silly - it is silly indeed. However, it is done this way to simplify it and focus on the post's main topic.

Once we run it, the result will be like this:

Lisa gives away basketball

Worker Bob received basketball

Worker Bob started processing basketball...

Worker Bob processed basketball

Eric gives away teddy bear

Worker Bob received teddy bear

Worker Bob started processing teddy bear...

Worker Bob processed teddy bear

Jenny gives away watermelon

Worker Bob received watermelon

Worker Bob started processing watermelon...

Worker Bob processed watermelon

Ben gives away box

Worker Bob received box

Worker Bob started processing box...

Worker Bob processed box

Zlatan gives away football

Worker Bob received football

Worker Bob started processing football...

Worker Bob processed football

If you followed along and ran this program, you might have noticed that the execution was done in no time. So, no problem then, right? Well, not really. I bet you have visited the post office in your life. And the chances are that you stayed in the queue, and maybe even in a quite long one. Then you know that the real-life processing of the parcels the customer would like to send or receive is way more complicated than this piece of code:

func (w *Worker) Process(item string) {

fmt.Printf("Worker %s received %s\n", w.Name, item)

fmt.Printf("Worker %s started processing %s...\n", w.Name, item)

fmt.Printf("Worker %s processed %s\n", w.Name, item)

}

Depending on the digitalization level of the post offices in the country of your residence, once you pass the parcel to the worker there, the following might happen:

they might request your ID

they might need to type your and the parcel's info into their system

they might scan the QR code attached to the parcel

they might need to "parse" your handwriting on a parcel and type it into the system

if you brought the item without the package, they might need to put it into a box or an envelope

you might need to sign some documents

you might need to pay for their service

you might have some questions for them

and so on and so forth

I'm trying to say here that the processing of one customer might take a while, so if we want to be 100% precise in the code, it will be fair to add some waiting time between the "started processing" and "processed" stages. Let's assume that the average processing time is 1 minute, then the code would look like this:

func (w *Worker) Process(item string) {

fmt.Printf("Worker %s received %s\n", w.Name, item)

fmt.Printf("Worker %s started processing %s...\n", w.Name, item)

// to simulate long processing

time.Sleep(1 * time.Minute)

fmt.Printf("Worker %s processed %s\n\n", w.Name, item)

}

As you can see, the only change we made was adding a time.Sleep(1 * time.Minute) part, which suspends the function execution for 1 minute. Obviously, if we run our code once again, it will take around 5 minutes for it to complete. And it is despite the fact that 1 minute is quite a generous estimate, as we could have easily picked up 5 minutes, and that would still be fair - the total execution would be around 25 minutes. That's far too long!

I hope the challenge we have is crystal clear as of now. How can we solve it?

Possible solutions

In an ideal world, the solution will be super simple: to have 1 worker per 1 customer. Then, in our scenario, if the average processing time is 1 minute, it will take exactly 1 minute to handle the entire queue. Impressive, right?

Well, it's pretty doable with 5 customers, like in our example, but what if the queue is 10 people long? What about 50? 100? It's obvious that in the real world, there are limits: money, time, space, etc., that's why the post office (or any other business, for that matter) won't hire that many employees to have a 1-1 ratio with the customers. What are the alternatives?

If we are limited by the number of workers, let's consider improving the quality of work. What if we try to reduce the amount of work the worker needs to do with the customer by doing the rest of the work later or by delegating to colleagues? Let's imagine that all the worker has to do is scan the QR code on the parcel, compare the photo from the system with the person standing in front, and pass the parcel to the other colleague - the customer can leave right away, as the rest of the activities will be done without their presence. Cool!

If you have an experience in programming, I bet you have already recognized this pattern - asynchronous execution. The beauty of such an approach is that the resources (the customer in our case) can be released fast, as the processing happens in a background fashion.

Concurrency vs Parallelism

If you want to dive deeper into this topic, there is no way that I can present it better than Rob Pike (one of the Go creators) did: https://go.dev/blog/waza-talkWe now clearly understand how to solve the challenge we faced, but before jumping into the code, we need to discuss Go concepts for asynchronous/concurrent programming. As the post title suggests, we'll explore goroutines and channels today.

Goroutines

A Tour of Go defines goroutines as

a lightweight thread managed by the Go runtime

The word "thread" suggests that if some part of the code is wrapped into the goroutines, the execution won't be sequential.

If this doesn't make sense - fear not; let's try to see that via the simple code example. Here is a printNTimes function that does what the name suggests: prints a string the number of requested times:

func printNTimes(s string, n int) {

for i := 0; i < n; i++ {

fmt.Println(s)

}

}

And let's call it from the main function to see how it works:

func main() {

printNTimes("Hello there.", 5)

printNTimes("General Kenobi. You are a bold one.", 5)

}

If we run this code, the output is as expected:

Hello there.

Hello there.

Hello there.

Hello there.

Hello there.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

This is the sequential order of execution we discussed above, meaning that there is a defined order:

printNTimes("Hello there.", 5)runs and finishes its executionprintNTimes("General Kenobi. You are a bold one.", 5)runs and finishes its executionthe application finishes the execution

Let's try to run one of the printNTimes as a goroutine to see a difference. But wait a minute, how can we do that? Luckily, it's super-duper simple in Go - the only thing we have to do is to add a go keyword before the function call:

func main() {

go printNTimes("Hello there.", 5)

printNTimes("General Kenobi. You are a bold one.", 5)

}

If you try to run this code, you might get different results. For instance, my first 5 attempts to run got this output:

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

I tried to rerun it and got this:

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

Hello there.

And even this:

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

Hello there.

Hello there.

Hello there.

Hello there.

Hello there.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

What's going on here? Why is the code wrapped into a goroutine so unpredictable and sometimes even not executed? These are good questions, and if you are familiar with concurrency/parallelism/multithreading from any other programming languages, you know the answer already, so feel free to scroll down ahead. For the rest, let's dive into this.

We discussed above that the goroutines are the lightweight threads managed by the Go runtime, and we need to use the go keyword to start a new one. However, there is one edge case that we didn't mention: if you run the Go application (or rather the main function, to be more specific), the Go runtime creates 1 goroutine and runs the app within it - it is called a main goroutine. Then, if we do go printNTimes("Hello there.", 5), the Go runtime creates a new goroutine which is a child (or a branch) from the main one. And here is the catch:

if the child goroutine is done before the main one - it's OK, the app execution goes on

if the main goroutine is done, the app doesn't wait for the child ones to be completed, but exits the execution

If this sounds too complex, let me use a simple example from real life. I'm a happy owner of the PlayStation game console and a remote controller for it. When I turn my console on (like running a main function and a main goroutine), PS starts. Then I have to explicitly turn my remote controller on and connect it to the console (like running a child goroutine). If I turn my remote controller off in the middle of the game (or it gets disconnected/runs out of power), the console will keep running as before (see the 1st statement above). But if I turn my PS off, my remote controller will stop working properly immediately (see the 2nd statement).

And this is precisely what happens in our code:

when we run the app, the main goroutine starts

go printNTimes("Hello there.", 5)starts a new goroutine - please, note it takes some time to start itwhile the Go runtime creates, initiates, and runs a new goroutine, the execution goes on, and the

printNTimes("General Kenobi. You are a bold one.", 5)the rest depends on many OS and hardware factors, but the possible outcomes are the following:

the

printNTimes("General Kenobi. You are a bold one.", 5)(and the app itself) finishes before the new goroutine starts - then there is no "Hello there" printed to the consolethe

printNTimes("General Kenobi. You are a bold one.", 5)(and the app itself) finishes in the middle of the child goroutine execution - then there are less than 5 "Hello there" messages printed to the console.the

printNTimes("General Kenobi. You are a bold one.", 5)(and the app itself) finishes after the child goroutine has finished its execution - then all the "Hello there" messages are printed to the console.

I believe it should make good sense now.

How can we fix that, though? We need to make the main goroutine wait a bit for the child to finish. There are elegant ways to achieve that, which we'll discuss in future posts. But we'll start with the simple one by forcing the main goroutine to wait for a dedicated amount of time (for example, 1 second) before exiting.

func main() {

go printNTimes("Hello there.", 5)

printNTimes("General Kenobi. You are a bold one.", 5)

// to prevent the program from exiting before goroutine finishes

time.Sleep(1 * time.Second)

}

time.Sleep(1 * time.Second) is the code that will do nothing (sleep) for 1 second.

If we run this code, we should see that all the 10 messages are printed:

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

Hello there.

Hello there.

Hello there.

Hello there.

Hello there.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

The chances are that you might get a different order of messages printed on your machine. And if you rerun the app again, the order might or might not change. This is the nature of the concurrent execution when the order is not guaranteed but decided by the Go runtime.

It is possible to compare it with real life: imagine you got a task to write "Hello there" 5 times (starting each from a new line) in a Google Doc / Microsoft Word document. And your colleague got a similar task, but with the "General Kenobi. You are a bold one." message. Both of you will have to use the same document to do that. Most likely, the result won't be like that if you both start writing at the same time:

Hello there.

Hello there.

Hello there.

Hello there.

Hello there.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

But rather this:

Hello there.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

Hello there.

Hello there.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

Hello there.

Hello there.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

General Kenobi. You are a bold one.

Or any other non-sequential combination depends on many factors like typing speed, copy-paste skills, internet connection speed/stability, etc. The same applies to the concurrent code.

Now we have learned the very basics about the goroutines, and we can create them. It is a good time to jump to another important Go concept - channels.

Channels

Why do we need a new concept alongside the goroutines? The thing is, while goroutines are pretty powerful, they have some limits. And one of them is that it is impossible to return any value from the goroutine. This means that the code like this won't compile:

func main() {

result := go add(1, 2)

fmt.Println(result)

}

func add(a int, b int) int {

return a + b

}

The error is:

./main.go:6:12: syntax error: unexpected go, expected expression

This limit makes sense if we think about it for a moment: the code inside the goroutine is executed asynchronously, meaning that the main program continues its execution. In that case, when the go add(1, 2) code runs, there is no result right away - it will be but some time in the future. And there is nothing to assign to the variable result := and nothing to print in the following line.

Different languages come up with various workaround for that: JVM ones (Java, Scala) introduced a concept of Future-s, while JavaScript/TypeScript operates with Promise-s and C# has Task-s. The idea behind these approaches is the following:

the asynchronous code returns an instance of

Futurewith the desired type within (intin our case)the

Futuredoesn't contain the value right away, but it will once the async execution is completedit is possible to request the value from the future by calling its

get()method - this will stop the program execution and wait until the result is ready

Our example in Java will look like this:

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) throws ExecutionException, InterruptedException {

Future<Integer> future = CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(

() -> add(1, 2)

);

System.out.println(future.get());

}

private static int add(int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}

}

And 3 is printed to the console.

Go creators decided to choose another path by introducing a concept of channels, as a place to put the value once the async execution is completed.

If we reference A Tour of Go once again, it says that channels are

a typed conduit through which you can send and receive values with the channel operator,

<-.

and the following example is provided:

ch <- v // Send v to channel ch.

v := <-ch // Receive from ch, and assign value to v.

The only missing part is how to create channels. Luckily, it's pretty straightforward:

ch := make(chan int)

where:

chanthe built-in channel data typeintthe data type of the elements that will be put into the channel

If we rewrite our code, it will look like this:

func main() {

ch := make(chan int)

defer close(ch)

go add(ch, 1, 2)

result := <-ch

fmt.Println(result)

}

func add(ch chan int, a int, b int) {

ch <- a + b

}

As expected, 3 is printed into the console.

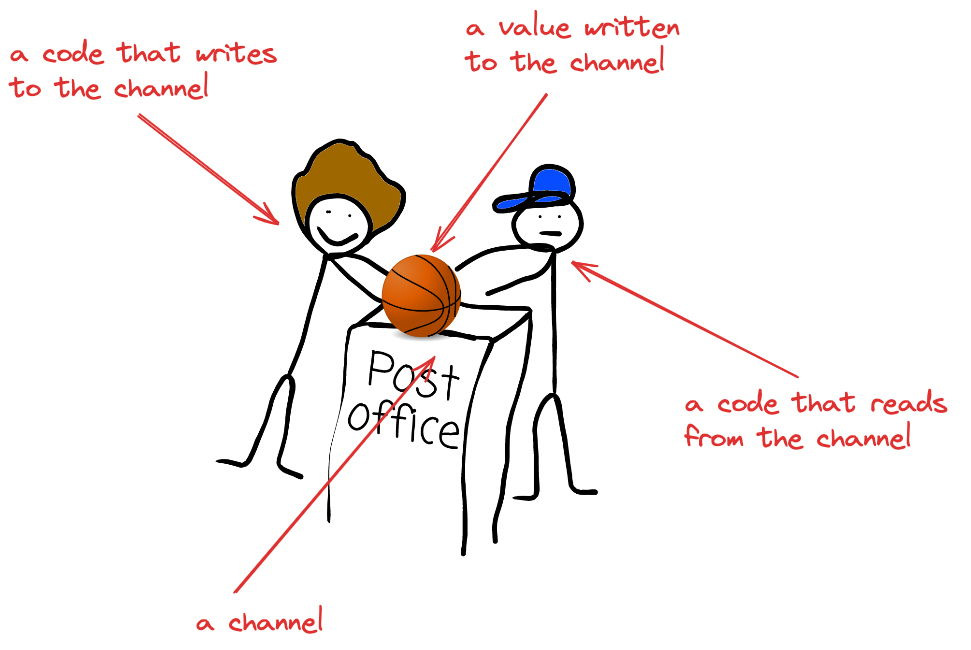

But how does this code work? To answer this question, let me take a step aside for the moment and go back to the post-office example to explain this. I hope you remember my drawing (or should I say a masterpiece) from there:

Such a beauty! But let me get back to business: we are interested now in the rightmost side of it, where the customer puts a basketball onto the post office desk, and the post worker takes it from there. This is a good representation of the channels, and here is the same part of the picture but close with the arrows and some text descriptions:

While this is a straightforward transaction, there are some important concepts behind it:

if there is nothing on the post office desk, the postman has nothing to take from it, so they just wait

there is a room for only 1 basketball on the post office desk

if there is something on the post office desk, the customer can't put their stuff there, so they just wait

once the customer puts the basketball on the desk, the postman picks it up reasonably fast - but it's not guaranteed that this will happen right away

if the post office desk is closed, it is not possible to put new items onto it, but the postman can get the item from the desk if there is something left

The same rules apply to the Go channels:

if the channel is empty and the code tries to read from it, the execution is blocked, and the program waits until there is an item in the channel

make(chan int)creates a channel that has room for only 1 item of typeint(we'll discuss further how to create channels with larger capacity)if the channel has an item within, the code that tries to put a new value into it is blocked until the channel is empty again

once the item is in the channel, the code that reads from it will pick it up soon

if the channel is closed, it is impossible to write into it (

panic: send on closed channel), but the reader can get the existing value from the channel. If the reader keeps reading from the channel, it will receive the default values (e.g.0forint)

I hope this part is clear, so now we are ready to take a look at the code from the above again:

func main() {

ch := make(chan int)

defer close(ch)

go add(ch, 1, 2)

result := <-ch

fmt.Println(result)

}

func add(ch chan int, a int, b int) {

ch <- a + b

}

Let's go through it step-by-step to see what happens here:

ch := make(chan int)creates a new channel of the typeintwith the default capacity of1defer close(ch)tells the program to close the channel once themainfunction is completed - that's a bit outside of the scope of this post, but TLDR: even though not necessary, it is a good practice to close the channels after they are not needed anymore.go add(ch, 1, 2)wraps a call to theaddfunction into a new goroutine and passes the channel from the previous step into the functioninside the

addfunction, the result ofa + bis written to the channel via thech <-piece of coderesult := <-chcode blocks the execution until thego add(ch, 1, 2)is completed and the result is passed to the channel; once the channel has the result from theaddfunction, theresult := <-chpiece of code reads it and assigns to theresultvariablefmt.Println(result)prints the result to the console.

Unlike the code from the section where we introduced goroutines, this one doesn't need any tricks like time.Sleep() to get the result before the app is finished. This is the beauty of the <-ch reading from the channel operation that waits for the result.

There is one last thing I'd like to discuss here before I wrap this post up - channels with a capacity larger than 1.

Buffered channels

That's what they called. To create such a channel with, let's say, capacity for 2 items, you have to do this:

ch := make(chan int, 2)

This is how we can use them:

func main() {

ch := make(chan int, 2)

defer close(ch)

ch <- 1

ch <- 2

result1 := <-ch

result2 := <-ch

fmt.Println(result1)

fmt.Println(result2)

}

You should see such results in the terminal:

1

2

As you can see, since the channel has capacity for 2 elements, we could do this:

ch <- 1

ch <- 2

without having anyone to read from there. If we try to do the same with the channel of the default capacity, the code will never finish but will rather wait forever:

func main() {

ch := make(chan int)

defer close(ch)

ch <- 1

ch <- 2

result1 := <-ch

result2 := <-ch

fmt.Println(result1)

fmt.Println(result2)

}

so the Go compiler will throw an error:

fatal error: all goroutines are asleep - deadlock!

goroutine 1 [chan send]:

main.main()

/n0rdy-blog-code-samples/20231204-go-channels-and-goroutines/05-buffered-channels/bufferedchans.go:23 +0x71

By the way, kudos to Go that its compiler detects deadlocks and fails on them rather than silently keeping the code in the blocked state forever.

fatal error: all goroutines are asleep - deadlock! means exactly what we have predicted: ch <- 2 tries to write to the channel that is already full -> the code waits -> the goroutine falls asleep -> since we have only 1 goroutine (main), it means that all the goroutines are asleep -> deadlock

To understand the concept of the buffered channels, let's get back to our post-office example again and take a look at this picture:

As you can see, the post office desk has become larger and has room for 3 items simultaneously. It means 3 customers can put their stuff onto the desk and leave, so the next ones in the queue can proceed. However, there is still only 1 post office worker, so that they will take the items one by one in the first-in-first-out (FIFO) order.

The similar rules apply here as for the channel with the default capacity:

if the channel is empty and the code tries to read from it, the execution is blocked, and the program waits until there is an item in the channel

make(chan int, n)creates a channel that has room for onlynitems of typeintif the channel has

nitems within, the code that tries to put a new value into it is blocked until the channel has a free capacity againonce the item is in the channel, the code that reads from it will pick it up soon in the FIFO order

if the channel is closed, it is impossible to write into it (

panic: send on closed channel), but the reader can get the existing values from the channel. If the reader keeps reading from the channel, it will receive the default values (e.g.0forint)

So, does this mean that the buffered channels are better than the default ones? Well, not really: as usual in software engineering (or in life in general), the answer is "it depends". We'll dive deeper into that later. However, even the add example we used today clearly shows that there is no need to have a buffered channel there since we expect to get only 1 value.

We did a good job today, and there is quite a lot of info to digest. Still, you should have a good understanding of the goroutines and channels (on top of my drawing skills) now, so we'll dive deeper into this topic next time and go through the built-in constructs to operate channels and goroutines, and get closer to the solution of the post-office long queue problem.

In the meantime, thank you for your time (that was quite a journey), and have fun! =)

Subscribe to my newsletter

Read articles from Mykola directly inside your inbox. Subscribe to the newsletter, and don't miss out.

Written by

Mykola

Mykola

...then something Tookish woke up inside him, and he wished to go and see the great mountains, and hear the pine-trees and the waterfalls, and explore the caves, and wear a sword instead of a walking-stick...