Rust Learning Note: Ownership and Borrowing

Raine

RaineThis blog is a summay of Chapter 5.1 and 5.2 of Rust Course (https://course.rs/)

A notable feature of Rust language is the ensurance of both memory security and runtime efficiency. Rust does not require programmers to manually allocate and release memory like C++, which may lead to memory security and leakage issue, but it also has no CG systems like Java and Python that impair efficiency. This feature of Rust is achieved by the ownership and borrowing mechanism.

Stack and Heap

Before we learn about the ownership mechanism, we need to first know how data are stored in memory.

Stack is a last-input, first-output (LIFO) data structure. The size of each stack element must be the same, so (in general) stack cannot store large data like objects, or mutable data. Stack operations (push and pop) are both highly efficient.

Heap is used to store data with unknown size and mutable data. When such data need to be stored, the operating system would allocate a memory space for storage, and store the address of the data in stack. Since heap operations require searching the storage location, they are generally slower in data.

In general, primitive data types and pointers are stored in stack, and reference data types (objects) are stored in heap.

Ownership Principle

To summarize the ownership principle in rust:

1. Every value can only be directly referred to by one variable.

2. When the variable leaves the scope, the value it refers to is also dropped.

Ownership Principle in Reference Data Type:

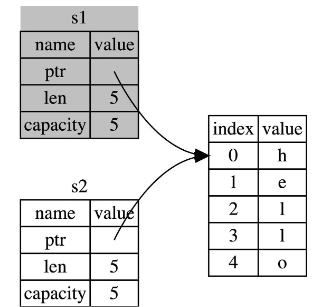

For a reference data type stored in heap like String, when a variable s2 is referred to variable s1, the ownership of the String object previously owned by s1 would be transferred to s2. After that, s1 will no longer be a valid reference (since we require every object only has one reference), and printing s1 would throw an error.

let s1 = String::from("hello");

let s2 = s1;

println!("{}, world!", s1);

Unlike many other languages (like Java and Python) that s1 and s2 can both refer to the same object, in Rust the referrence in moved from s1 to s2.

Fig 1. s1 is discarded when the ownership transfers (Image reproduced from Rust Course)

Ownership Principle in Primitive Data Type and Pointers:

For primitive data type and pointers that are stored in stack, the situation is different. In the example below, x is assigned to a pointer of "hello world". When y is assigned to x, the ownership of value does not transfer from x to y. Instead, y is assigned to a copy of the value in x.

fn main() {

let x: &str = "hello world";

let y = x;

println!("{}, {}", x, y);

}

The same happens when x refers to a primitive data type like int. In this case, x and y will both be 5, without affecting each other. The following data types can all be directly copied:

integer and float

bool

char

tuple (if the elements in the tuple are all able to be copied)

immutable reference &T (but not mutable reference &mut T)

let x = 5;

let y = x;

println!("x = {}, y = {}", x, y);

For reference data type, clone method allows the creation of a copy of object. However, the copying of a whole object is inefficient and should not be frequently used.

let s1 = String::from("hello");

let s2 = s1.clone();

println!("s1 = {}, s2 = {}", s1, s2);

Ownership Transfer in Function Calls

Similar to assignment statements, the transfer of ownership also happens when objects are passed as function parameters or return values.

fn main() {

let s = String::from("hello");

takes_ownership(s);

let x = 5;

makes_copy(x);

}

fn takes_ownership(some_string: String) {

println!("{}", some_string);

}

fn makes_copy(some_integer: i32) {

println!("{}", some_integer);

}

In the case above, when s is passed into function takes_ownership as the parameter some_string, the ownship of String object also transfers from s to local variable some_string. As a result, after the execution of takes_ownership, the String object is dropped along with local variable some_string, and s is no longer valid.

However, in the case of makes_copy, a copy of the value of x (5), as passed as the parameter of some_integer, so variable s is not affected.

fn main() {

let s1 = gives_ownership();

let s2 = String::from("hello");

let s3 = takes_and_gives_back(s2);

}

fn gives_ownership() -> String {

let some_string = String::from("hello");

some_string

}

fn takes_and_gives_back(a_string: String) -> String {

a_string

}

In this case, the gives_ownership method assigns the ownship of the String object to s1 (s1 replaces the local variable some_string as the owner of the object). For s2 and s3, the ownship of string s2 is transferred to s3 through the takes_and_gives_back. As a result, s3 now refers to the String object and s2 is no longer defined

Reference

Rust also supports references by pointers, called borrowing, in addition to direct transfer of ownership.

fn main() {

let x = 5;

ley y = &x;

assert_eq!(5, x);

assert_eq!(5, *y);

}

In the code above, y = &x assigns y to a pointer to the value of x. *y is used to retrieve the value indicated by the pointer, which is 5. Thus, the two assertion statements are all true. However, if we use assert_eq!(5, y), an exception would be thrown since y represents a pointer, not an integer.

Immutable Reference

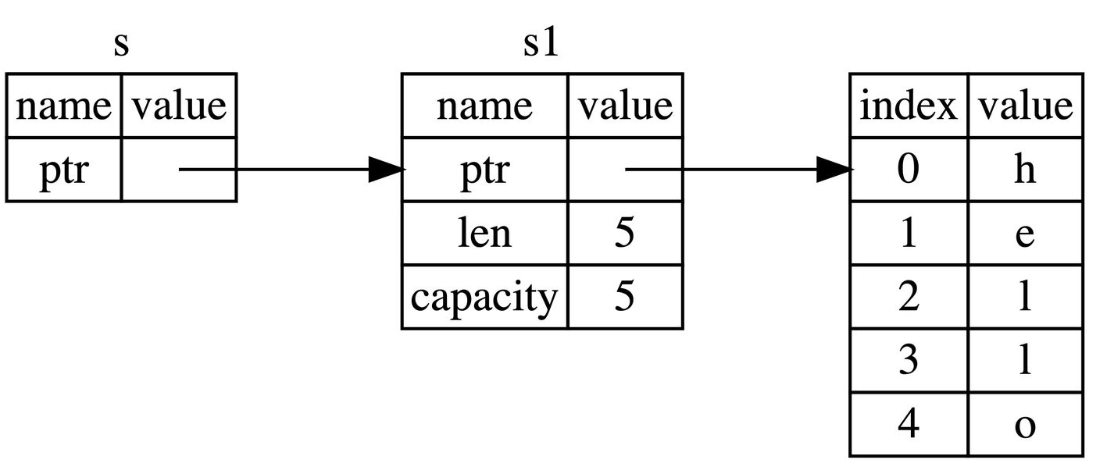

An immutable reference allows a variable to access an object without owning it. In the code below, a pointer to s1 (&s1) is passed into calculate_length, and s1 still owns the String object. However, an immutable reference does not allow the pointer len to modify the String object.

fn main() {

let s1 = String::from("hello");

let len = calculate_length(&s1);

println!("The length of '{}' is {}.", s1, len);

}

fn calculate_length(s: &String) -> usize {

s.len()

}

Fig 2. pointer s referring to s1, which owns the actual object in heap (Image reproduced from Rust Course)

Mutable Reference

Creating a mutable reference includes the following steps: 1 making the variable to be referred to mutable. 2 Adding keyword mut after the & in the reference.

fn main() {

let mut s = String::from("hello");

change(&mut, s);

}

fn change(some_string: &mut String) {

some_string.push_str(", world");

}

However, there are certain restrictions on the use of mutable references.

Firstly, only one mutable reference can exist in a scope. This restriction is to prevent data competing: two or more pointers accessing and mutuaing the same data. For example, the code below would throw an exception since two pointers coexist in the same scope.

let mut s = String::from("hello");

let r1 = &mut s;

let r2 = &mut s;

println!("{} {}", r1, r2);

Secondly, also as an attemptin to prevent data competing, mutable references and immutable references cannot coexist, as in the code below

let mut s = String::from("hello");

let r1 = &s;

let r2 = &s;

let r3 = &mut s;

println!("{}, {}, and {}", r1, r2, r3);

Non-Lexical Lifetimes (NLL)

NLL is an optimazation made in the compiler to reduce the trouble caused by the restrictions of mutable references. NLL makes the end of a reference's scope to the place where it is last used instead of the whole scope of the variable. For instance, the code below would not cause errors since r3 is defined after the last use of r1 and r2.

fn main() {

let mut s = String::from("hello");

let r1 = &s;

let r2 = &s;

println!("{} and {}", r1, r2);

let r3 = &mut s;

println!("{}", r3);

}

Dangling References

Dangling reference is a situation when the value referred to by a pointer is released, and the pointer is pointing to a void or meaningless value in the memory. Dangling references are forbidden in Rust, and all references must be clear before dropping a value.

fn main() {

let reference_to_nothing = dangle();

}

fn dangle() -> &String {

let s = String::from("hello");

&s

}

In this code, the String object is dropped after the function dangle returns. However, reference_to_nothing is assigned to a pointer to the dropped object. This code would not pass the Rust compiler. To fix it, we should return s directly instead of &s

Subscribe to my newsletter

Read articles from Raine directly inside your inbox. Subscribe to the newsletter, and don't miss out.

Written by