Architecting for "X"

Connor Avery

Connor Avery

Background

In recent years, I've worked across many varying architectures on AWS in a consulting capacity.

These architectures and the applications which ran on them were built to do different things. All of them come with fundamental trade-offs towards what they were building for. Some organisations might want to be cost-effective, whereas others desire to be highly performant and accept a higher cost.

What you are building for is your "X" and architecting for that will inevitably come with trade-offs. Without knowing your "X", your architecture won't satisfy your requirements. Allow me to take you through the understanding of building good architecture for your "X".

What I'd like you to keep in mind when continuing to read this blog is that there is unfortunately no hard or fast set of rules you can apply to your architectural design: everything you decide has a cost in some regard and it's not always monetary.

This blog is inspired by a series of talks I've recently given at AWS Events in the UK. In these talks, I revisited concepts that, while familiar to some, are crucial for all engineers—whether they're just starting out, mid-career, or highly experienced. My aim is to encourage learning, provide a grounding in fundamentals, and offer deeper insights into the field.

Use this post to encourage discussion with this blog - Share it with your fellow engineers & be ready to have productive conversations around your understanding of architecture and even how your current architecture is built.

Architecture, who?

When I'm talking about Architecture, I mean your system's underpinning structure. Architecture covers a wide range of aspects, from how your services are hosted, where your data is stored, how you access data, who has access and your network topology.

Think of a skyscraper in your nearest city, without a good foundation, you can't build anything. Without an initial understanding of what you require upon that foundation, you'll struggle to build the next Burj Khalifa with severe issues and potential risks.

Why you should care

Your architecture governs quite a lot without you realising, from simple things like your developer experience to more important aspects such as testability and security.

Whether you are starting from scratch, looking to implement new features or re-evaluating current architecture to better fit your "X", these three elements should cement (excuse the pun) the reason your architecture is important to you.

Defines the 'work' ahead - Whether building from scratch or refactoring, any changes to architecture require work to achieve them.

Defines your domain boundaries - Not everyone cares about or needs access to every part of your system. Equally, neither does any one particular part of your system.

Defines the balance of your "X" - Whether that be performance, cost, success (fault tolerance) or other.

Architecture 🤝 Software

There is an interconnected nature between architecture and software. Think about a hypothetical application for a moment: the application has been programmed to read and write data from a MySQL database.

The decision as to how that data will be stored has largely been determined already, that is, it needs to be MySQL schema compliant or any changes will have a cost associated with changing it. Refactoring the software to work with another type of database and 'moving' the data to its new location.

In a parallel universe, that piece of software has yet to be written and the questions are just being asked of how and where it stores data, evaluating the use cases ahead of time.

How the data is stored, its access patterns and availability requirements may warrant a NoSQL database as the 'better' choice.

Other examples of this interconnected nature include:

Highly available application - Data must be ephemeral in case of failure. Web 2.0 websites relied on local server storage a lot of the time and therefore weren't compatible with horizontal scaling: where the same data wasn't present on the server of other servers behind the loadbalancer.

Fault-tolerant application - Any individual part of the architecture could fail and the system still functions or "fails gracefully" as retry functionality, dead letter queues or other failure scenarios are handled by the architecture and software.

Whether actions are synchronous or asynchronous - You wouldn't want an API call (service A) waiting on an application that only runs on a schedule (service B). In this example, you might want to architect service B to not run on a schedule and in fact, be available 24/7. Or better yet, question why service A is synchronous - does it need to be?

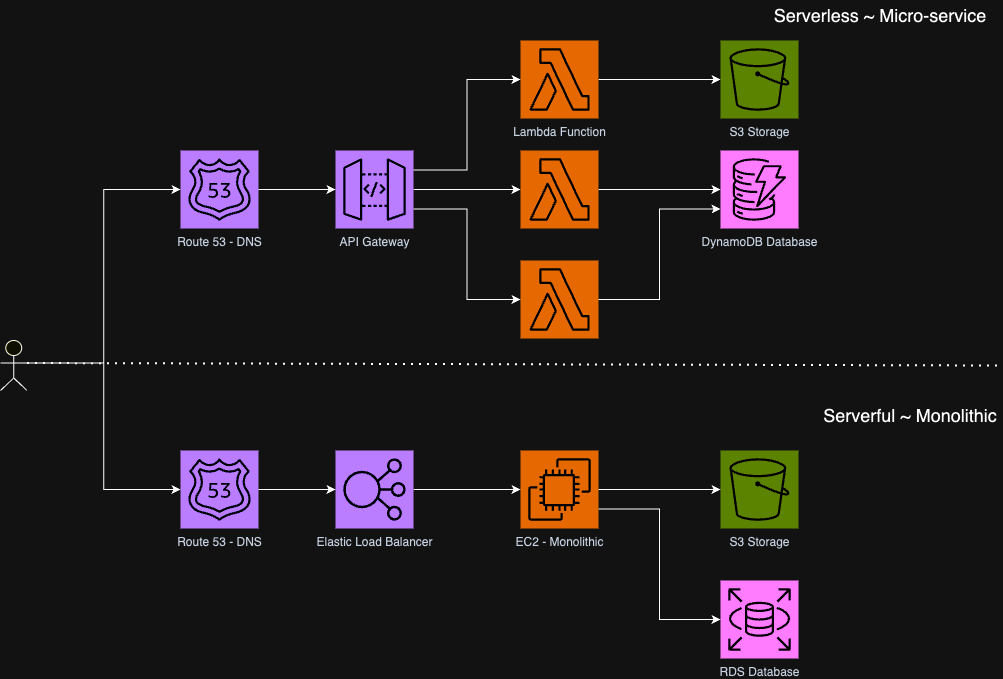

I won't touch into too much detail here, but the architecture & the software that resides upon it, both influence each other when deciding many aspects, such as Server vs. Serverless or Monolith vs Micro-service. Your "X" plays a part in this decision.

I've written a blog on exactly those trade-offs recently, take a read (later of course) of Monoliths in the 21st Century: Nostalgia or Necessity.

Diagrams

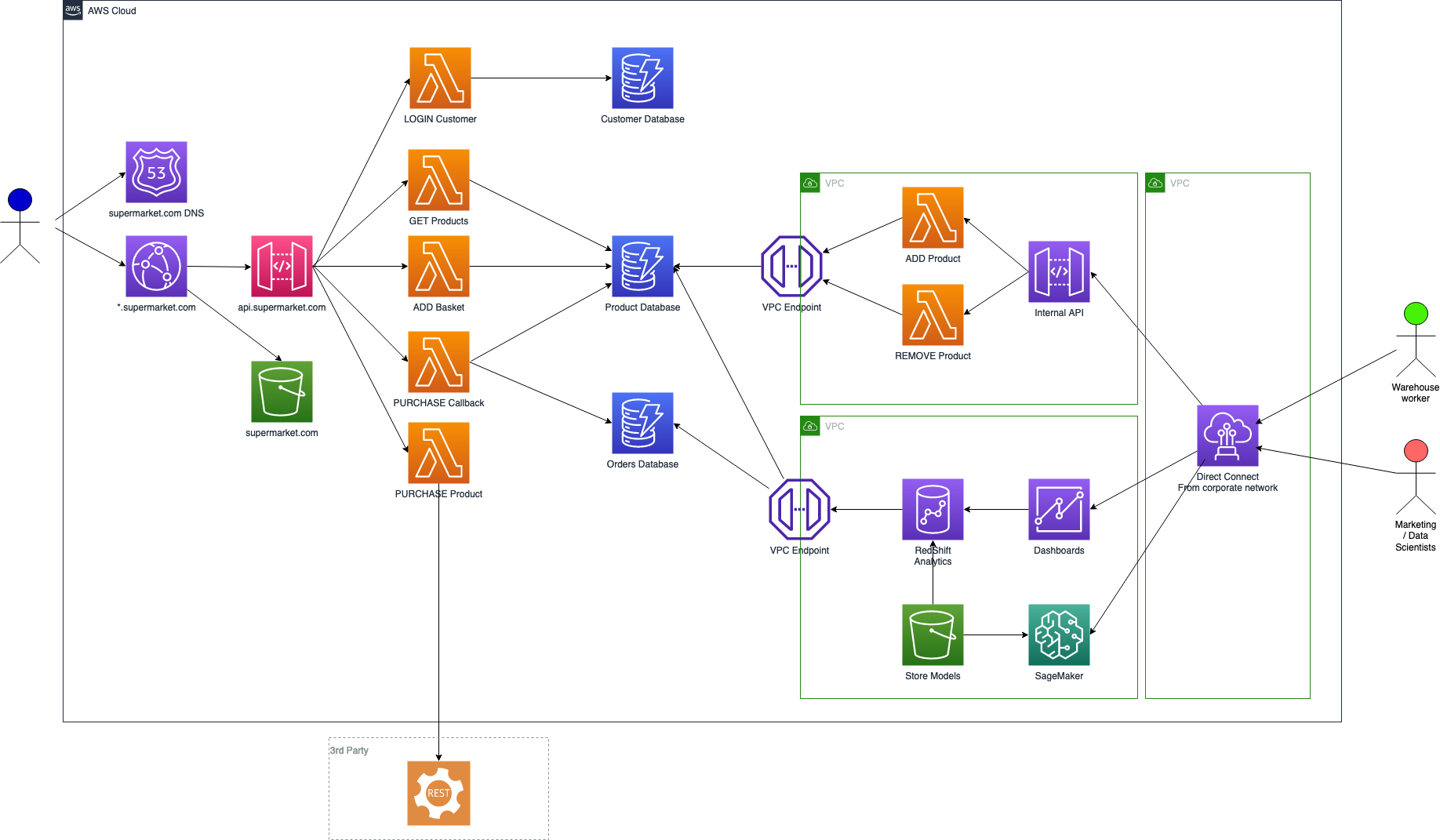

Architecture is often visualised to make it easier to understand and follow the flow of actions through the system as a whole. You'll have likely seen a diagram like the one below before [created on Diagrams.net]:

A lot could be desired from the diagram I've created for a hypothetical e-commerce website, however, the quality of the diagram and what it must include is like linting - everyone has an opinion and nothing will ever satisfy everyone.

What matters is that your architecture, or architectural diagram is understandable for yourself, your team and the people around you. Change it if not!

Architectural Influences

When looking to build your architecture, you must first understand the landscape you find yourself in.

There are elements you control, others you can influence and some you must simply abide by.

Understand your landscape

You might be working within a heavily regulated industry, where considerations such as deanonymisation of data is a legal requirement, or encryption can only be completed by a hardware security module and not by software-defined methods because the utmost security is required. This is the regulatory impact.

Your organisation may wish to impose mandatory requirements and restrictions, for instance, in this blog post I've referenced Amazon Web Services, your organisation may make it mandatory to use Microsoft Azure as the cloud solution of choice. The difference mightn't same great but there are pros and cons to consider on all sides. For instance, in a hypothetical situation, AWS offers more 'free' usage of managed services such as Lambda functions vs. Azure where Azure Functions offer no free invocations (this difference immediately affects your financial cost). This is the business decision impact.

Knowledge, previous experience and skills of yourself, your team and your organisation as a whole will also need to be understood. If you are designing or extending existing architecture, you're also restricted slightly by the existing infrastructure and applications if you can't re-design or refactor OR it mightn't be 'owned' by you and therefore can't be influenced. This is the restriction impact.

What's your X?

With your landscape understanding, you now have an empty canvas, where the borders have been defined and understood. Next is to understand your X, and what are you architecting towards.

Your 'Y' is the application you wish to make available and its infrastructure requirements - Which mightn't be defined yet.

The X comes in many shapes and sizes; but it is balanced between and not exclusive to any individual attribute: Cost, Performance and Success (the ability to handle failure).

You might find similarities between this pyramid of architecture with something else, the CAP theorem. An advantage for any particular side is a disadvantage for one or two of the others.

How you architect your system will continuously bring forward the questioning and reasoning against your X.

For example, a fully serverless application with relatively stable traffic may be the cheapest cost to run monthly, but due to the knowledge and skills required may cost more to develop vs. a conventional server (serverful) design.

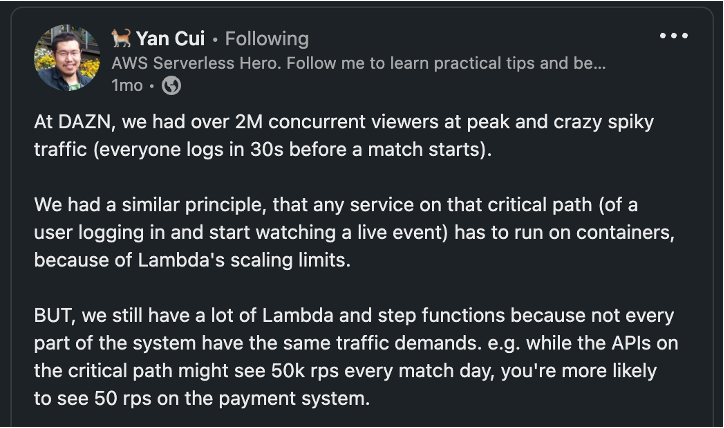

In conjuction you don't need to be fully embedded in any particular 'camp', ie micro-service vs. monolithic, serverless vs. serverful. You can and should use each tool appropriately for how it best serves you and fits your X. Use the right tool for the job.

Credit: Yan Cui on LinkedIn.

The Well-Architected Framework

It'd be remiss of me to not call out Amazon Web Services' very own framework for creating robust and stable architectures for systems and the decisions you need to weigh up.

To not repeat what is already available, please visit the well-architected framework website.

Principles of Great Architecture

The best thing at the time

As has been mentioned, your architecture can and will change depending on various factors not limited to what skills or knowledge you hold at the moment, the imposed SLAs and current requirements on your system.

What you build today may be perfectly suitable for now but the future has a vote and may warrant a change. That doesn't mean you've violated this principle if done correctly. If you've considered all factors possible, you've taken a step forward with the information you have at hand. The reflection principle will offer more information and offer insight to improve.

Don't get stuck in analysis paralysis, real usage will provide enough insight to confirm suspicions.

What skills and knowledge do you have right now?

Do you know your real service level agreements?

What is your backup policy? Do you need one?

Are you repeating yourself?

Explainable and justifiable

"Brain before build" - Designing your system before writing any code is strongly advised!

Having resources such as documentation or diagrams for the design of your architecture and all associated reasonings for the choices you've made, will allow you to collaborate with others, validate assumptions and ensure you are architecting towards your X.

Don't underestimate the wildcard questions when designing architecture, which can be overlooked without thought-provoking questions.

Are you re-inventing something that already exists? It could be that a SaaS product already does as you require.

Is it worth refactoring OR build new?

What could your future use cases be? How are you ensuring you aren't 'trapping' yourself?

Causes reflection

Great architecture design, the aspect of designing and the final product will hopefully cause reflection on existing system processes. You may identify inefficiencies or areas for real improvement in some way because you understand your architectural influences and landscape.

Reflection happens at all stages of the design.

Is what we're building achieving the original requirements?

- Are the requirements fixing the problem or masking it?

Is it maintainable?

Is it testable?

Are you using the correct thing at the correct time?

What's to come?

With everything we've discussed above, it's very likely that in the future we could see AI tooling which could calculate an approximate cost both monetarily and engineering timewise. Tooling such as this could heavily influence decisions of which architecture to choose for your "X".

Something else to consider is the growth of Software-as-a-Service products which will complete a wide range of requirements from applications and architecture and it may become more beneficial to purchase "off the shelf" than to build your own. It's also important when considering SaaS products that it's someone else's problem, you are simply gaining value.

Still confused, where should you start?

As mentioned earlier, it's very difficult to understand how your "X" will define your architecture without having a full context of your situation and the problem you are trying to solve.

Some people reside strongly in opposing thought camps; when starting with your architecture, some believe in going fully Serverless and therefore more likely "micro-service" architecture.

Whereas others believe it's quicker to produce a monolith and work backwards.

In my personal opinion, I don't care for either - I use what I feel fits best, with the available knowledge, tools at hand and my "X". I may be inclined to build a monolith if my "X" is speed to market (an "X" I've not spoken of so far) or be inclined to build a hybrid server-serverless architecture if the system requires it.

Whichever you feel comfortable with right now, start with that. You'll soon reflect and change for new requirements going forward and have a better understanding when you revisit your design. With more information, you'll be able to choose the best thing at that time once more.

Subscribe to my newsletter

Read articles from Connor Avery directly inside your inbox. Subscribe to the newsletter, and don't miss out.

Written by

Connor Avery

Connor Avery

Full Stack Cloud Engineer working primarily on AWS. I'm a Pythonista at heart, but enjoying working with JS/TS and React.