Learning Note: Learning the Implementation of Programs with Assembly Language

Raine

RaineThis article is a summary of Chapter 10 of:

Yazawa, H. (2015). 程序是怎么跑起来的[How Program Works] (L. Fengjun, Trans.). People's Posts and Telecommunications Press

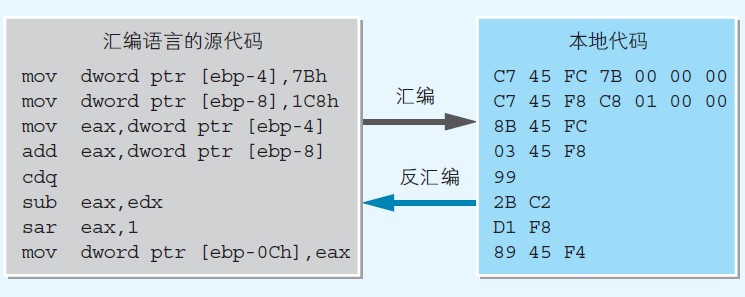

Correspondance between Assembly Language and Native Code

CPU can only execute native code, and code written in advanced languages need to be compilered to be executed. Assembly language is a low-level language that uses mnomeics, keywords that have one-to-one correspondence with native code. Code written in assembly language need to be assembled with assembler to native code, and native code can be easily disassembled to assembly language.

Fig 1. One-to-one correspondence between assembly and native code. Image reproduced from (Yazama, 2015)

Generating Assembly Code with Compiler

In the following example, we will write a simple program in C, and use the compiler to generate the corresponding assembly code to see how advanced language is connected with assembly language.

int AddNum(int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}

void MyFunc() {

int c = AddNum(123, 456);

}

In Borland C++ compiler, -c means only compile without linkage, and -S means generating assembly code

bcc32 -c -S Sample.c

The resulting file Sample.asm, contains assembly code generated by the compiler:

_TEXT segment dword public use32 'CODE'

_TEXT ends

_DATA segment dword public use32 'DATA'

_DATA ends

_BSS segment dword public use32 'BSS'

_BSS ends

DGROUP group _BSS,_DATA

_TEXT segment dword public use32 'CODE'

_AddNum proc near

;

; int AddNum(int a, int b)

;

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

;

; {

; return a + b;

;

mov eax, dword ptr [ebp+8]

add eax, dword ptr [ebp+12]

;

; }

;

pop ebp

ret,

_AddNum endp

_MyFunc proc near

;

; void MyFunc()

;

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

;

; {

; int c = AddNum(123, 456);

;

push 456

push 123

call _AddNum

add esp, 8

;

; }

;

pop ebp

ret

_MyFunc endp

_TEXT ends

end

Here are a few points to note about before reading the assembly code:

1 Directives that are not converted to native code:

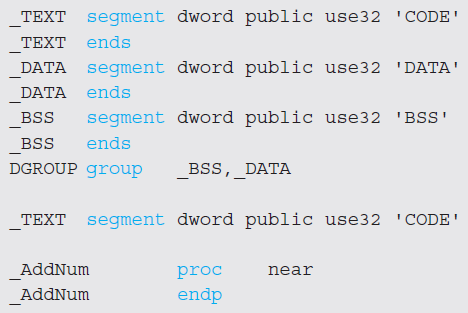

In assembly, there are a set of codes, called directives, that are used to set assembly options and program structure. They do not have corresponding native code. The highlighted keywords are directives in the code.

Fig2. Directives in assembly code. Image reproduced from (Yazama, 2015)

Code between segment and ends are called segment, which is used to define a consecutive memory space. The code above defines three segments: TEXT for storing instructions, DATA for storing initialized data, and BSS to store uninitialized data. The TEXT segment and TEXT ends surrounding AddNmum and MyFunc indicate that the two functions are both inside TEXT segment. This is to ensure that the compiled code are grouped together even if the source code is mixed with other data. The directive group combines segments BSS and DATA to a single gorup called DGROUP.

In assembly, functions are represented as procedures, a procedure always has a "_" at the beginning of its name and is between proc and endp.

2 The "opcode + operand" grammar:

Code in assembly follows the structure opcode + operand, that is, an instruction and its associated data (or only the instruction itself). Here is a table of common instructions:

Table 1, Common instructions (the "and" should be "add"), Image reproduced from (Yazama, 2015)

Translation:

| opcode | operand | result |

| mov | A, B | assign B to A |

| add | A, B | assign A + B to A |

| push | A | push A to stack |

| pop | A | assign the value from stack to A |

| call | A | call function A |

| ret | return function value |

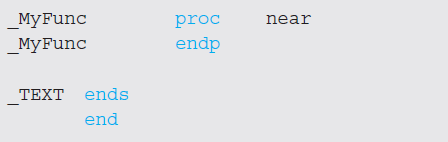

At runtime, the CPU would read the instruction and data and process them in registers. Different registers have different functions:

Table 2. Registers in x86 CPU. Image reproduced from (Yazama, 2015)

3 mov command:

mov opcode has two operands: the location to store the data and the one to read data. mov ebp, esp means assigning the value in ebp (base register) to be the data in esp (stack pointer register).

If the data source is within [ ], it means that value in this location is not interpret as literal values but as memory address. For example, mov eax, dword ptr [ebp+8] means assigning the value in eax (addition register) to be the value at address (ebp + 8). If the value at ebp is 100, data at address 108 will be read, dword ptr (double word pointer) means reading 4 bytes from memory address.

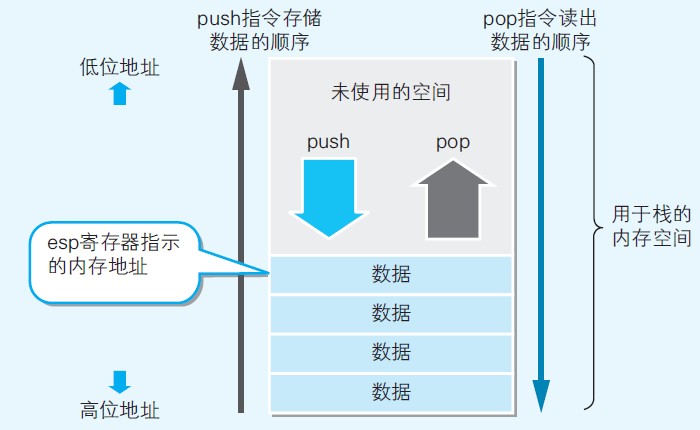

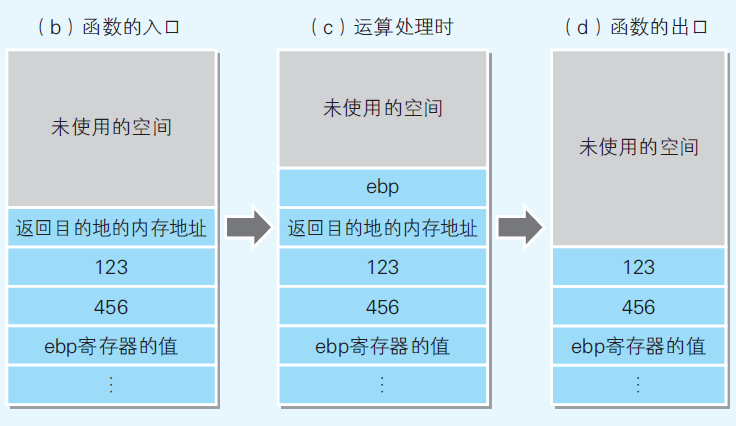

4 push and pop commands for stack:

push and pop operations pushes and pops elements in stack. Each operation can process 4 bytes of data. The esp (stack pointer register) stores the top of the stack, and is automatically updated after each push and pop operation.

Fig 3. Push and pop operations for stack. Image reproduced from (Yazama, 2015)

Function Calls in Assembly

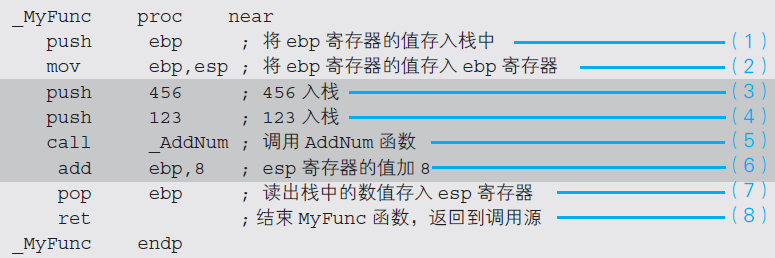

Now let's look at the assembly code for MyFunc:

Fig 4. assembly code for MyFunc. Image reproduced from (Yazama, 2015)

In the code above, we may first focus on line 3 to 6. Line 3, 4 pushes parameters 456 and 123 into stack. The order is reversed from the order of parameters AddNum(123, 456), since when retrieving from stack we will get the same order.

At line 5 we call the function AddNum. The call command would automatically push the address of the next line (line 6) into stack, and when the function returns ret command would pop the address of line 6, so we can continue executing the rest of the program after a function call.

Line 6 clears the two parameters 456 and 123 in stack by adding 8 to esp (one integer takes 4 bytes). Technically, the two integers still remain in memory, but they will no longer be accessed.

Note that there is no corresponding assembly code for assigning the result of AddNum to variable c in the source code. This is because variable c is never used in the following program, so its initialization is omitting during the optimization of compiler.

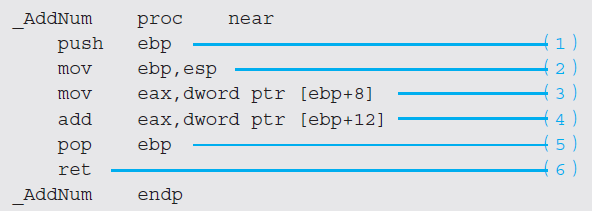

Operations Inside the Function

Fig 5 Assembly code for AddNum. Image reproduced from (Yazama, 2015)

Line 1 and line 5 pushes and pops the value in ebp to and from stack. Since ebp may store values bafore the function call, and we want to use ebp in the function, we need to temporarily store the previous value in ebp in stack, and return the stored value when the function returns.

In line 2, we assigns ebp with the value in esp. Since esp does not support indexing with [ ], we need to move the index to ebp. Line 3 and 4 read the two values 123 and 456 through indexing and add the two value together. With indexing, we can access values in stack wihtout pop operations. The addition is processed in eax register, which supports numerical operations. In C language, the function return value must be returned through eax register. From the whole process above we can see that function parameters are passed through stack, and return values are passed through register.

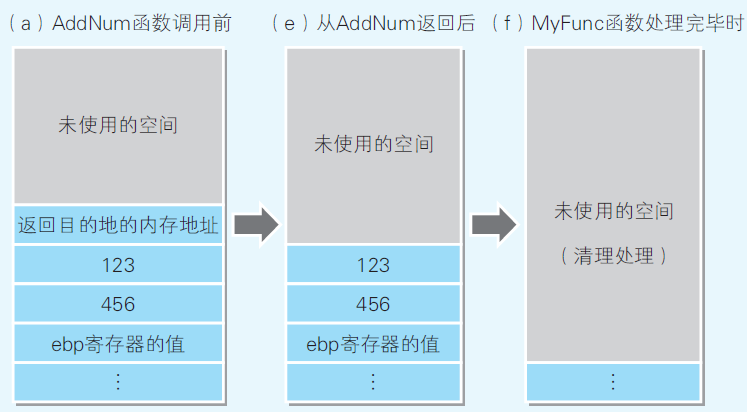

Fig 6, Fig 7 are the stack frames in MyFunc and AddNum, they together show the values in stack during the whole program:

Fig 6. The stack frame of MyFunc. Image reproduced from (Yazama, 2015)

Fig 7. The stack frame of AddNum. Image reproduced from (Yazama, 2015)

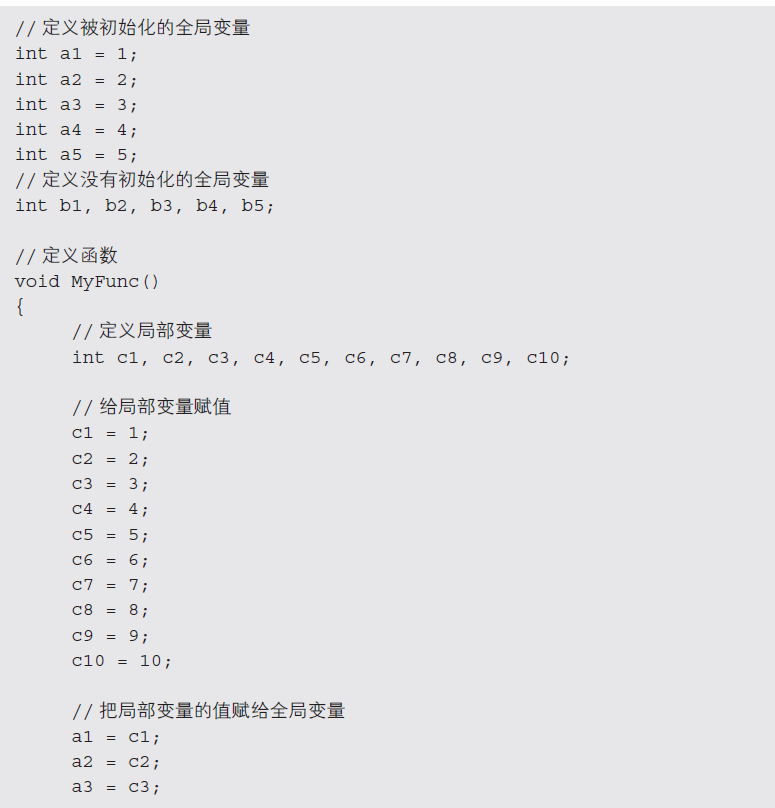

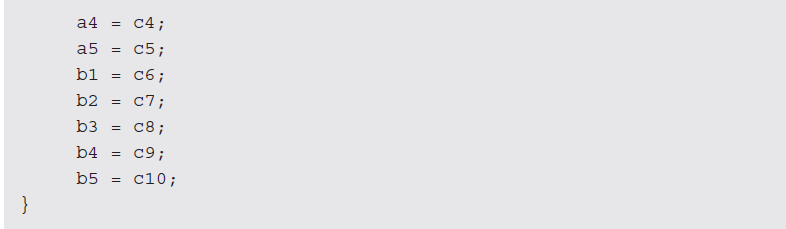

Global Variables and Local Variables

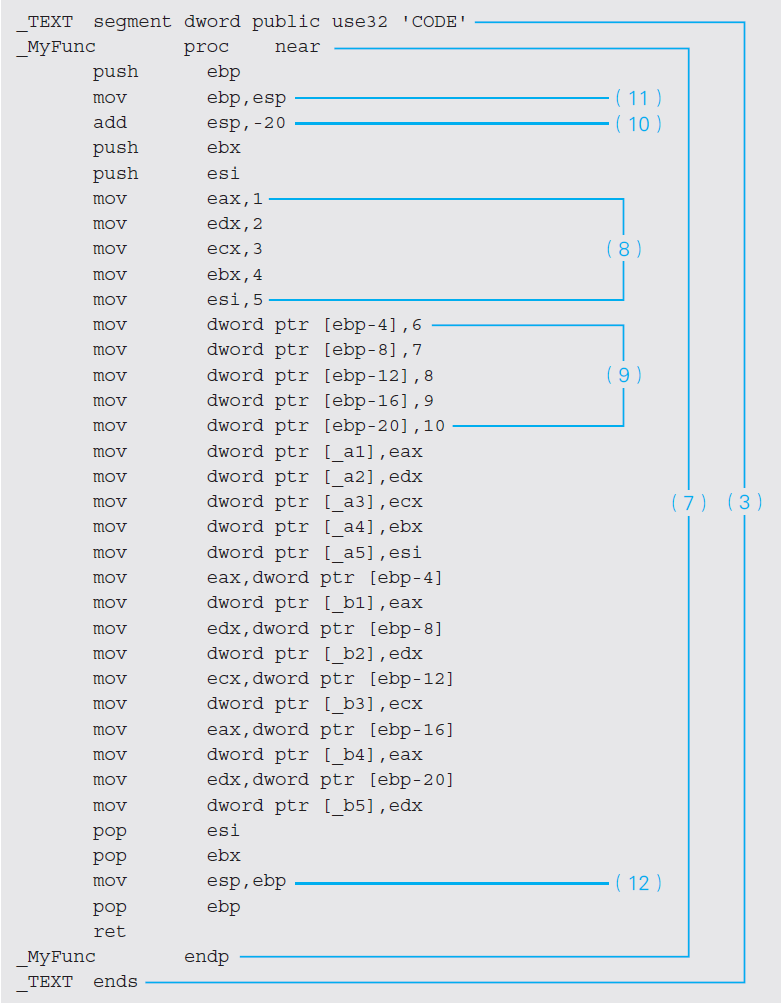

Fig 8. An example code containing global and local variables. Image reproduced from (Yazama, 2015)

Fig 9. The assembly code from code in Fig 8. Image reproduced from (Yazama, 2015)

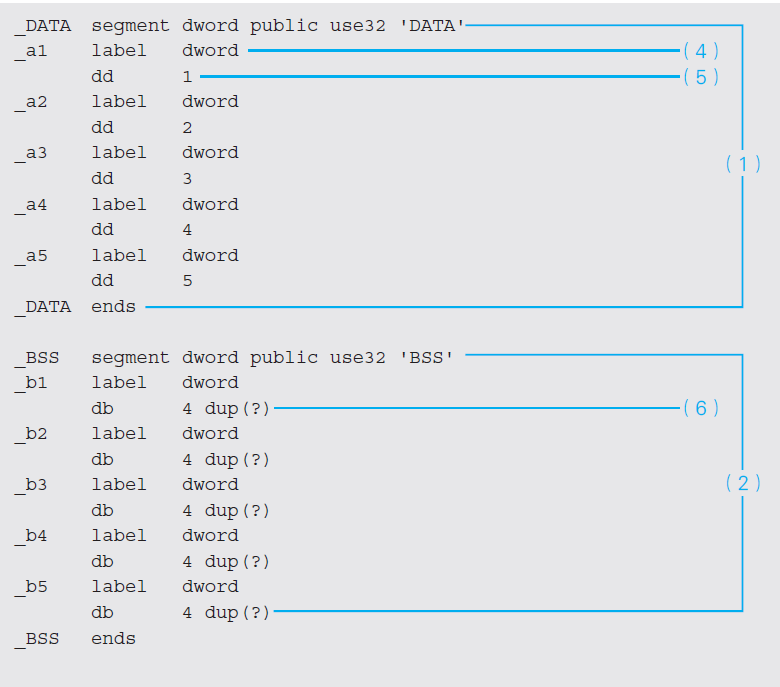

We talked about segmentation on the description of directives. In the program, we can notice that global variables a1 - a5 that are created and initialized are stored in DATA segment, and global variables b1 - b5 that are not initialized the moment of their creation are stored in BSS segment. The code is stored in TEXT segment.

For the assignment statements for a1 to a5, label dword defines the variable label, which is the relative location to the starting address of DATA segment. dd (define double word) creates a memory space of 4 bytes used to store the int value of the variables.

For global variables b1 to b5, db 4 dup(?) means assigning a space with 4 bytes, but the value is indeterminate. Normally, indeterminate values in BSS are pre-initialized to zero.

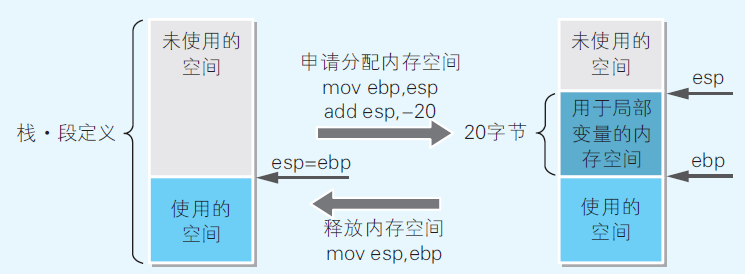

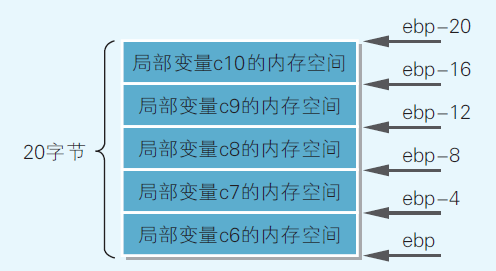

Unlike global variables that are stored in memory, local variables are stored in registers or stack, and will be cleared once the register or stack is cleared. The compiler would first use available registers to store local variables (since operations on the registers are much faster than those on the stack), and then use the stack if all registers are used. In (8), local variables c1 to c5 are stored in 5 registers, and in (9), variables c6 to c10 are allocated on the stack. Note the add esp, -20 operation (11) pre-arranges 20 bytes memory on stack to stored the five integers (Fig 10), and the address of c6 to c10 are from [esp-4] to [esp-20]. (Fig 11)

Fig 10. Allocate 20 bytes on stack for c6 - c10. Image reproduced from (Yazama, 2015)

Fig 11. The storage of c6 - c10 on stack. Image reproduced from (Yazama, 2015)

Representing Loops in Assembly

void MySub() {

}

void MyFunc() {

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

MySub();

}

}

xor ebx, ebx

@4 call _MySub

inc ebx

cmp ebx, 10

jl short @4

The code above represents how a for loop in C is implemented with compare (cmp) and jump (jl) operation in assembly.

Here's a step-by-step breakdown of the code:

xor ebx, ebx: this operation sets the value in ebx to be zero (the same as int i = 0). XOR operation between two values returns 1 if the bits are different and 0 when the bits are the same, so one value having XOR operation with itself is always 0.

call MySub calls the empty function

inc ebx increases the value in ebx by 1, the same as i++

cmp ebx, 10 compares the value in ebx with 10 (the comparision is implemented by substraction and checking of flag register). Whether the result is positive, zero, or negative is stored in flag register.

jl (jump on less than) checks whether the result in flag register is negative, that is whether value in ebx is less than 10. If i is less than 10, short @4 sets the program counter to the index @4, where the program begins to execute another loop.

Representing Conditional Statements in Assembly

Similar to loops, conditional statements are also implemented with jump in assembly. The explanations are shown in code comment.

void MySub1() {}

void MySub2() {}

void MySub3() {}

void MyFunc() {

int a = 123;

if (a > 100) {

MySub1();

} else if (a < 50) {

MySub2();

} else {

MySub3();

}

}

_MyFunc proc near

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

mov eax, 123 ; move 123 to eax

cmp eax, 100 ; compare eax with 100

jle short @8 ; if eax <= 100, jump to @8 (else if)

call _MySub1

jmp short @11 ; complete if branch, jump to @11

@8: cmp eax, 50 ; compare eax with 50

jge short @10 ; if eax >= 50, jump to @10 (else)

call _MySub2

jmp short @11 ; complete else if branch, jump to @11

@10:call _MySub3 ; the else branch

@11:pop ebp

ret

_MyFunc endp

Subscribe to my newsletter

Read articles from Raine directly inside your inbox. Subscribe to the newsletter, and don't miss out.

Written by