Hoisting in JavaScript

Dana Ciocan

Dana Ciocan

I am endlessly fascinated by the fact that JavaScript has become the language of the web. When I first learned about it as a teenager, it was almost exclusively used for animations that CSS couldn't do yet - button rollovers and the like.

I recently picked up an old book from a charity shop called JavaScript: the Good Parts by Douglas Crockford - it is hilariously thin, which tickled me, so of course I bought it. I never read it at the time (in 2008 that is), but reading it in 2024 it got me thinking about how for a while there, JavaScript was a language that required us to use a lot of workarounds, mostly due to the fact that it had been created in just ten days and was never intended for such big purposes. Even though I hadn't read the book at the time, I had definitely encountered a lot of the issues the book describes and as it mentioned tricks like var this = that; I got all nostalgic and thought a series about some of these concepts and issues and some of the JavaScript history could be interesting.

It's true that ES6 has added syntactic sugaring and new layers on top of the original language to make it feel like more official and less hacky, but all of these old concepts are still there if you pop the hood. While it's not essential to understand these concepts to use JavaScript, I think it helps certain things click into place that might not have before. And, let's face it, who wouldn't want to learn about the Temporal Dead Zone??

Hoisting with var

Here's a question for you: what would you expect the following code to do?

console.log(platypus);

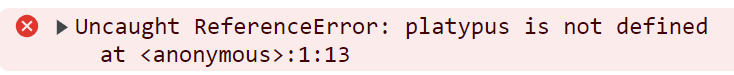

If you said error, you're right! It will throw a ReferenceError as follows:

The reason for this is fairly self-explanatory - the platypus variable does not exist, so how is JavaScript supposed to know what to do?

So what about this code?

console.log(platypus);

var platypus = 'Perry';

Would you have guessed that it prints out undefined? Don't worry, you're not the only one! This behaviour occurs due to a process called hoisting - the word "hoisting" is defined as:

To raise or haul up, often with the help of a mechanical apparatus

And this gives a pretty good clue as to why the above code works. It turns out that JavaScript will move variable declarations (but not the assignments) to the top of the program scope and it does this before it runs any other lines of code.

So you can think of the above code as:

var platypus; // Platypus is defined but has no value

console.log(platypus); // Outputs `undefined`

platypus = 'Perry'; // Now the value of `platypus` is set to 'Perry'

To make things even more confusing, declarations using let and const work differently. Let's look at how and why.

Hoisting with let and const

If you try and run the same code above but using let or const instead of var, you will get a different result:

console.log(platypus); // Throws a ReferenceError

const platypus = 'Perry';

console.log(sister); // Throws a ReferenceError

const sister = 'Candace';

This is not because these variables aren't hoisted - they are - they are just treated slightly differently than variables declared using the var keyword.

They are put in the "temporal dead zone" - is anyone else hearing the Twilight Zone theme music in their heads right now??

Temporal Dead Zone (TDZ)

This has got to be the coolest name for a programming concept, right? It sounds like it's straight from a science fiction novel. Sorry, having a small geekout moment here, let's focus!

So whereas variables declared with the var keyword are available in the scope immediately once they have been hoisted, variables declared with let and/or const get put in what's called the "temporal dead zone" - the analogy that is coming into my head right now is from a boardgame called Arkham Horror where players can get "lost in time and space" and they're put in a little holding area to the side of the board, where, once they have spent the requisite number of turns recovering, they can come back onto the main board. The main board is your program and "lost in time and space" is the temporal deadzone. I guess it only works if you've played that game but hopefully it makes some kind of sense either way!

Once the interpreter hits the line where the variable is actually assigned a value, the variable is retrieved from the temporal dead zone and available for use. To illustrate:

// Any line before this, `platypus` is in the TDZ and...

// any statements that reference `platypus` will result in an error

const platypus = 'Perry'; // `platypus` is retrieved from the TDZ

// `platypus` is available to be used

console.log(platypus); // Will output 'Perry'

Why does hoisting even happen?!

I don't know about you, but I like knowing why something weird is happening, rather than just how it happens. It seems that hoisting is a side effect of the way the JavaScript interpreter works.

Basically, JavaScript code is interpreted in two phases:

First phase: variable and function declarations are processed and memory is set aside for them

Second phase: the interpreter processes the statements and the code is executed

Brendan Eich, the creator of JavaScript, has himself admitted that hoisting was an unintended consequence of how JavaScript was written and the fact that it was written in such a short amount of time (ten days allegedly!):

Why is hoisting in ES6 different?

Hoisting with var is super confusing and definitely not how you would expect a programming language to work. JavaScript appears to be the only language that has this mechanism too - some other languages have similar concepts, but they're still not quite like this.

The let and const keywords from ES6 were designed to help mitigate the confusion a lot of developers experienced using variables before they had been declared and putting variables in the temporal dead zone before they're used (as cool as it is!) is merely the workaround required to make JavaScript function like other languages.

I think the key takeaway here is that hoisting is why usage of var has pretty much disappeared from modern JavaScript, even though it is still around and nothing really stops you from doing so. Well, apart from maybe your linter!

Subscribe to my newsletter

Read articles from Dana Ciocan directly inside your inbox. Subscribe to the newsletter, and don't miss out.

Written by

Dana Ciocan

Dana Ciocan

I'm a Senior Engineer working at Octopus Energy. I love diving deep into big problems and surfacing with a workable solution. I also love making my own garments, cooking, crafting and gardening.