Surveys and the "True Score" Mistake

Chris Chapman

Chris Chapman

Increasingly, I think there is a deep and mostly unstated assumption about survey research that drives profound misunderstanding: the belief in a "true score".

Researchers and their audiences expect that there is an underlying real value that we can know — about product questions such as feature preference and willingness to pay, as well as social questions such as policy preference or likelihood to vote for a candidate. We want to find and report that true score with some confidence.

Surveys and polls are considered "good" insofar as they assess such latent values. Analysts use methods and statistics that reflect that fundamental premise. For example, the notion that there is a true value to be assessed through sampling leads to classical statistics tests of inferential hypothesis testing and confidence intervals.

In this post, I explain why I believe the assumption is profoundly mistaken, and how we should think about surveys instead. I won't pretend to have all the answers.

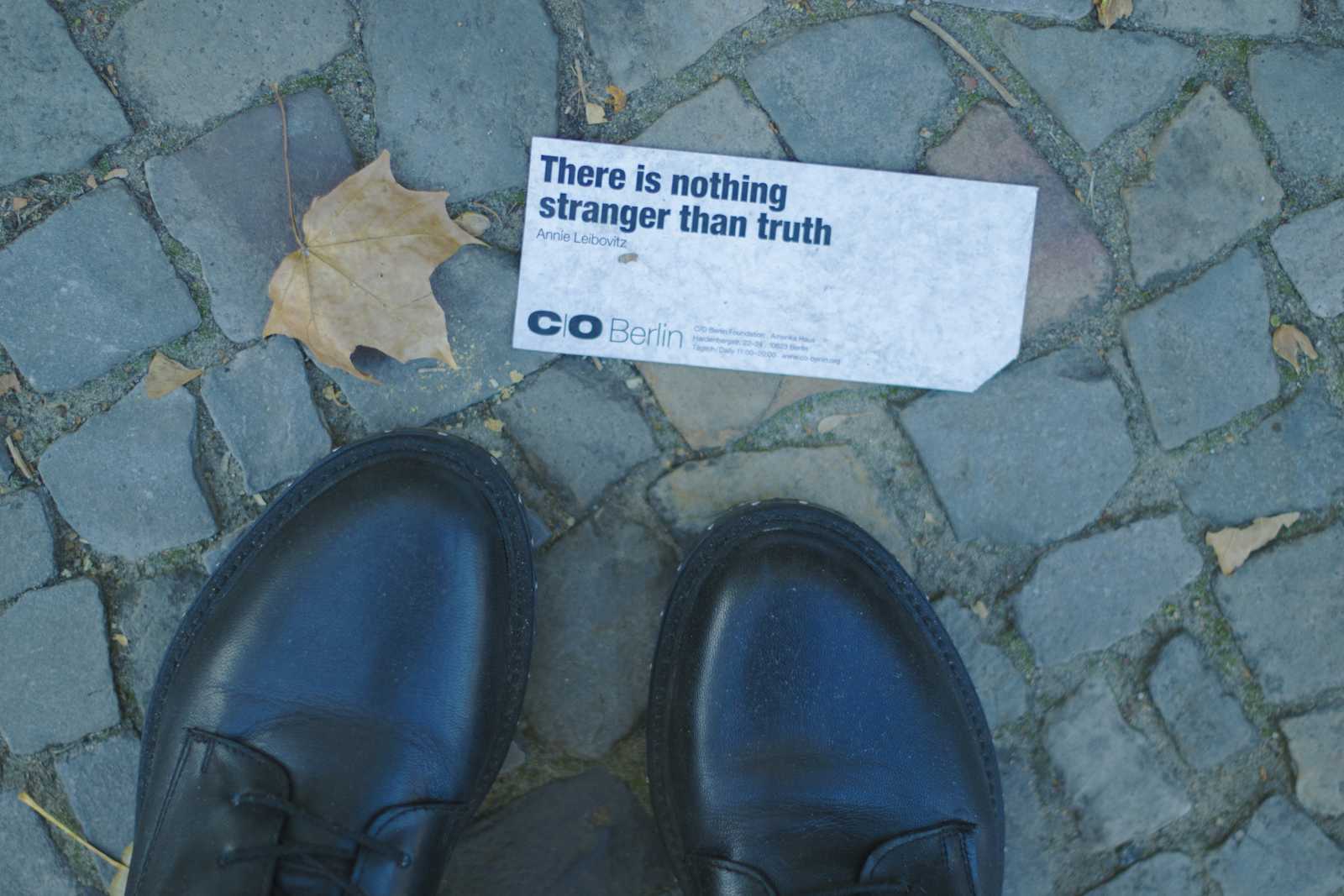

The short version is this: survey responses are motivated communication, not expressions of some other latent truth. Our research efforts must be designed to reflect this. Surveys do express truth ... but it is not the truth of some true score as usually assumed. Instead, it is the truth of what respondents tell us, reflecting many influences.

Examples of the Mistake

The underlying problem is the mistaken belief that there is a latent, unobservable and yet real "true value" that underlies survey assessment and other UX metrics.

I'll give a canonical example in moment, but first here are a few areas where I see this problem occur repeatedly:

Customer satisfaction. We act as if "CSat" is a stable property we can uncover and then probe for its causal determinants and influences.

Satisfaction with product features. We assume that overall CSat is composed of satisfaction with individual elements, which can be assessed independently.

Intent to purchase. We assume that "intention to purchase" is a state that can be accessed and reported by a respondent.

Willingness to pay. We act as if WTP is a property of a product or a feature, such as, "What is the willingness to pay for a 0.5" larger smartphone screen?"

Voting. Moving over to the public opinion realm, there is an assumption that somehow we can probe, "What if the election were held today?"

As I'll describe, all of those are misconceptions. I do not argue that there is no truth, but rather that truth is more subtle than the naive beliefs above.

A Specific Case

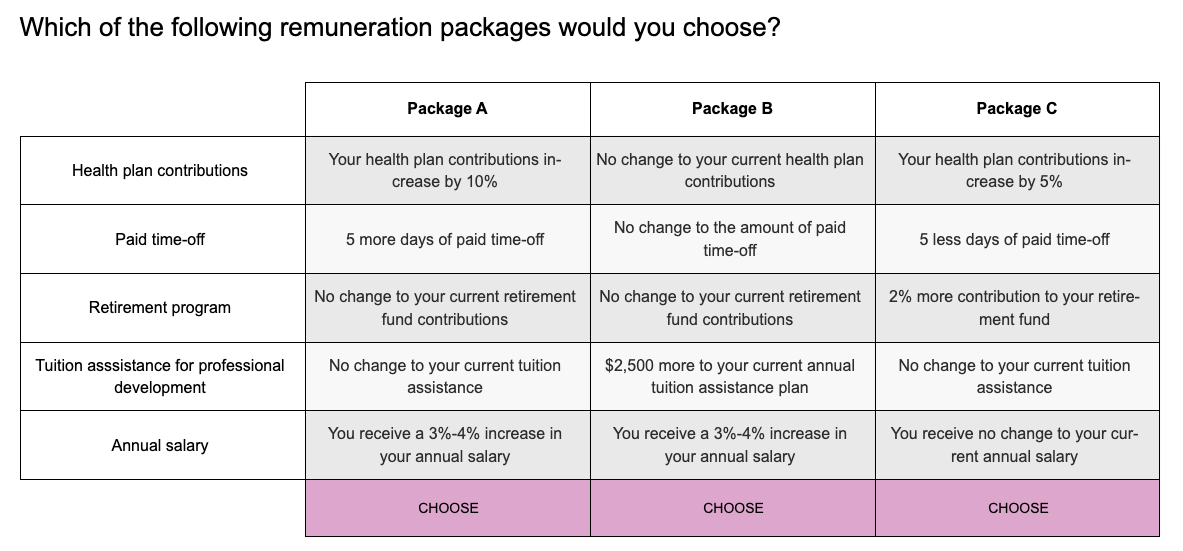

When I worked at Google, there was an annual employee survey that asked a question similar to this:

A survey author with a naive interpretation of this question might assume that:

there is such a thing as satisfaction with compensation

that respondents can access the degree of satisfaction through introspection

that respondents will report such introspection to some degree of accuracy

that the response scale is adequate to capture their report

As for the salary surveys, a running joke among a few colleagues at Google was, "Anyone who says they are satisfied with their salary is not competent to work here." I'll discuss that response later in this post.

Surveys as Motivated Communication

The two most important things for researchers and stakeholders to know are:

Respondents do not answer surveys for our reasons, but for their reasons

Respondents do not owe us responses that align with our concept of "truth"

A shorthand expression of those two facts is that survey responses are motivated communication.

Respondents take surveys for many reasons, such as:

They are interested in the topic

They want to help the research or its sponsor

They are incentivized with pocket money, points, or the like

They are survey researchers and like to see other surveys

They want to complain about a product or topic

They are bored

They wish to sabotage the research

They want to earn money to take care of themselves or their families

All of those are legitimate reasons to take a survey. It is our job as survey authors to anticipate and design survey contexts, contents, and analyses with respect to such motivations.

Similarly, when answering individual items on a survey, respondents adopt various motivated reasons for item responses:

Answering in the way they believe is truthful

Exaggerating to look better or for social desirability

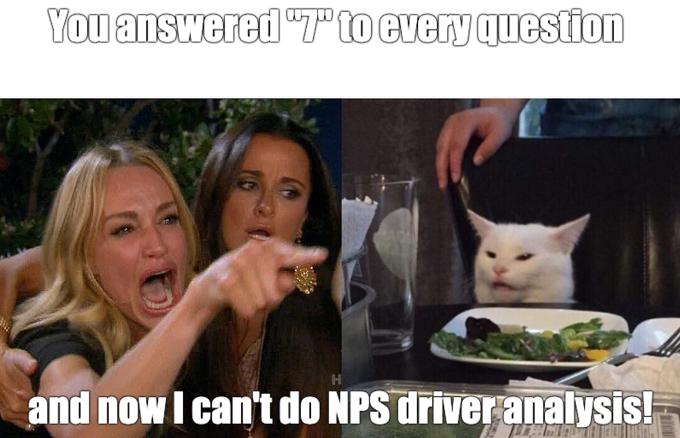

Speeding to get through the survey

Answering randomly because they don't understand an item or can't answer as they wish

Trying to dismiss an intrusive survey to get back to their desired task

Complaining about a product, service, person, etc.

Attempting to "steer" the results of the survey in some way

Answering maliciously for various reasons

Quitting the survey because it is too long or otherwise annoying

All of those are legitimate ways to answer survey items. No one owes us any particular kind of response or any particular reason why they responded!

None of this means that survey results are wrong or useless. It simply says that we must interpret all of our data rationally, with awareness that results may not mean what we superficially hope they mean.

To put it differently, respondents (usually) are not "lying" in their answers, and they are not bad respondents for having motivations that differ from ours.

What We Should Do as Survey Authors

As survey researchers, our job is to design surveys in such a way that we maximize responses and motivations that align with the decisions we need to make.

As product researchers, presumably we are running a survey because there is some decision we are informing. We want respondents to answer in ways that align with giving a real-world (albeit imaginary) latent "truthful response" to inform our decision.

That means we should:

Be transparent and fair (discouraging malicious responses)

Offer reasonable incentives (encourage responding; discourage malice)

Write simple, clear, and comprehensive items (discourage randomness)

Have short and responsive surveys (discourage speeding and quitting)

Use robust methods such as randomized scales and randomized experimental designs and methods (limit bias from speeding or random responding)

Be careful not to intrude or derail respondents' tasks (use intercepts sparingly)

Provide 1-2 open ends to obtain additional feedback (accept complaining)

Side note.You might wonder about an "honesty statement" at the beginning. Some researchers have claimed that asking respondents to agree to answer honestly increases the quality of survey data. Some related research itself has become controversial (pointer). I don't take a position on that, but my opinion is that well-designed surveys don't require us to demand that respondents answer "honestly."

Wait, What about Bots?

You're no doubt aware that survey-taking bots are a crisis in survey research (example). In fact, bots are so much a crisis that some researchers have given up and claim that complex bots may be "data" (see this post about LLMs).

Well, you guessed it: I think bots are an understandable way for respondents to answer surveys ... IF the survey developer or platform allows them and provides appropriate motivation. If people can make a living by automating surveys ... well, why not?

That doesn't mean I want bot data. Rather, it is part of our job as survey developers to guard against them by not allowing them and decreasing the motivation.

Unfortunately, some survey platforms are interested in collecting "any data" and at the lowest cost, regardless of the quality. No amount of screening, data cleaning, or modeling can turn bad data into good data. At best, we recover some data while introducing a lot of post hoc bias.

A complete consideration of bots is out of scope here, but at a high level we must use carefully designed sample platforms, robust survey design, and robust analysis.

Back to the Salary Research

Earlier I showed an item about employee salary satisfaction:

That particular survey had a known, enumerated sample so it didn't suffer from bots. But when we think about it from a motivation perspective, we find several other problems:

Respondents are motivated to give answers in particular directions.

They might say they are dissatisfied because that could influence decisions about base salaries.

Or they might report high satisfaction because they worry about being tracked and then being laid off, fired, or otherwise punished.

The motivation of the survey authors is unclear, and it might not be credible even if they stated it.

The response scale is standard ... and yet it is bizarre because — I assume — it is not connected to anything the company really cares about. Salaries are not decided in order to maximize satisfaction but in order to attract and retain employees vs. their other choices of jobs.

A better item would focus on the employee side of that specific decision. For example, we might ask about salaries vs. competitors. Such an item might even be amenable to calibration (e.g., by asking about some known to be higher or lower) ... but I digress from the topic at hand!

The best way for a respondent to think about such an item is from a game theory perspective. I do not know the motivations or likely actions of the authors of such a survey at a company so there is no possible way to address them. At the same time, my personal salary is a vital topic to me. The net result is that I should answer such a question in the way that benefits me.

FWIW, I would suggest a reasonable game theory response is this:

If the survey is credibly anonymous, a respondent might say they are very dissatisfied. (BTW, using the end points of a scale maximizes the influence on statistics.)

If the survey is attributed to the respondent and they worry about their job, a rational response is to say they are satisfied. That's not high enough to be suspicious.

If the survey is attributed to the respondent and they don't worry about their job, a rational response is to say they are dissatisfied. That's no doubt honest, because almost everyone would like a higher salary!

Notice that none of those reasonable responses says anything about actual satisfaction. That's why the authors should use a different item altogether that more specifically addresses the real decision they are making.

BTW, my colleagues' claim that anyone saying "satisfied" shouldn't work there was based on the assumption that situation #2 above didn't apply (being worried about one's job). Until 2023, that was not a systemic concern at Google (but then the layoffs happened).

After response #2 is eliminated, a rational game theory response is to report some degree of dissatisfaction. Remember, there is no particular moral high ground in survey research ... or at least, we shouldn't assume that there is!

For the survey authors, the key point is to focus on the decision being made (such as whether to raise salaries or not) and then design survey items that address that decision.

For example, a conjoint analysis survey might ask, "which job would you choose?" across several randomized possibilities. Here's an example (as discussed here):

By varying the job attributes and salaries, such a survey can identify employees' preferences and likely choices to stay or leave, relative to salary levels.

Conclusion & More Reading

My conclusion is this: survey responses are motivated by many factors, and we as survey authors should accept that reality, stop pretending that answers approximate "reality," and design our surveys to be robust to respondent motivations.

Specifically, I find it helpful to say that there is no true score that somehow underlies a survey item. There are only answers that help us make a decision or take some action. If we stop pretending that we are accessing truth, while fighting off "lying" respondents, we will design better surveys with less bias and more direct results.

More Reading? Kerry Rodden and I say much more about survey design, items, analyses, and unintentionally introduced biases in Chapters 4, 8, and 13 of the Quant UX book.

Or, if you're interested in conjoint analysis and forced tradeoffs among survey choices, check out MaxDiff in Chapter 10 of the Quant UX book, and Conjoint Analysis in Chapters 9 and 13 of the R book.

Cheers!

P.S. If the company is reading, I will predict with 100% certainty that employees will be more satisfied with higher salary. That finding is free of charge.

Subscribe to my newsletter

Read articles from Chris Chapman directly inside your inbox. Subscribe to the newsletter, and don't miss out.

Written by

Chris Chapman

Chris Chapman

President + Executive Director, Quant UX Association. Previously: Principal UX Researcher @ Google; Amazon Lab 126; Microsoft. Author of "Quantitative User Experience Research" and "[R | Python] for Marketing Research and Analytics".