How the Internet Works: Networking

J3bitok

J3bitokTable of contents

- What is Networking

- UnderSea Cables

- Routing

- IANA

- Regional Internet Registries (RIRs)

- Stakeholders that work with Afrinic in Kenya

- Internet Exchange Point (IXP)

- Automated Systems

- Role and Key Aspects of Automated Systems in Making IXP work effectively

- Public and Private IP Address Assigned by IANA & RIRs

- Automated Systems merge for Data Exchange and Interoperability between different Service Providers/Servers

- How Trust Plays a Crucial Role in Various Aspects of Internet Operations:

- Identified IXPs in Kenya

- Border Gateway Protocol

I have been taking the Cloud Engineering Course at ALTSchool Africa and it has been an interesting roller coaster we have learned Linux, and Bash Scripting, among other topics that are fundamental in the cloud.

The latest one has been how the internet works and it is really interesting that we use our phones, and different internet service providers, access different CDNs, search different things on the internet, and might not fully understand the bottom line of how the internet works to the point where we browser and get the right response back.

We recently saw reports of internet or server downtime last month and was faulted to undersea cables that were damaged (this might have sparked a lot of curiosity to many of us coz what the correlations of Safaricom's data bundles or WIFI to the undersea cables or maybe Microsoft servers too).

I was covering this topic and thought I could also consult ChatGPT to help with a more detailed breakdown of each key aspect of networking to help with understanding how the internet works from an aspect of networking. I will just put them together here:

What is Networking

Networking encompasses a broad range of technologies, protocols, and systems that enable communication and data exchange between devices and networks across the globe.

Networking involves the design, implementation, and management of interconnected systems and infrastructure to facilitate the exchange of information and resources. It encompasses various layers and protocols of the OSI (Open Systems Interconnection) model, including:

Physical Layer: The physical layer involves the transmission of raw data bits over physical media such as copper cables, fiber optics, wireless radio waves, and satellite links. It includes technologies such as Ethernet, Wi-Fi, and cellular networks.

Data Link Layer: The data link layer is responsible for framing data packets into frames, error detection and correction, and controlling access to the physical media. Technologies such as Ethernet, PPP (Point-to-Point Protocol), and MAC (Media Access Control) addresses operate at this layer.

Network Layer: The network layer provides end-to-end communication and routing of data packets across multiple networks. It includes protocols such as IP (Internet Protocol), ICMP (Internet Control Message Protocol), and routing protocols like BGP (Border Gateway Protocol) and OSPF (Open Shortest Path First).

Transport Layer: The transport layer ensures reliable data delivery between endpoints and manages end-to-end communication sessions. Protocols such as TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) and UDP (User Datagram Protocol) operate at this layer.

Session Layer, Presentation Layer, and Application Layer: These layers handle higher-level functions such as session management, data encryption, data compression, and application-specific protocols. Examples include HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol), SMTP (Simple Mail Transfer Protocol), and DNS (Domain Name System).

Networking also involves concepts such as network security, quality of service (QoS), network management, and network troubleshooting. It encompasses the design and deployment of local area networks (LANs), wide area networks (WANs), and the Internet itself, as well as emerging technologies such as cloud networking, software-defined networking (SDN), and Internet of Things (IoT) connectivity.

UnderSea Cables

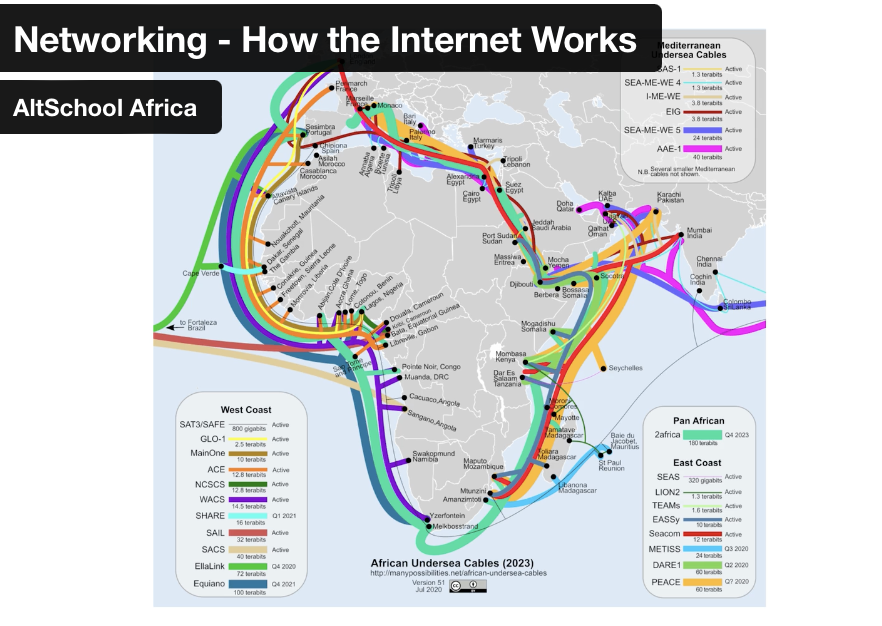

Undersea cables, also known as submarine or subsea cables, are critical components of the global telecommunications infrastructure, facilitating the vast majority of international Internet traffic and telecommunications data exchange. Here's an overview of undersea cables:

Purpose: Undersea cables are laid on the ocean floor to carry telecommunications signals, including Internet data, voice calls, and video transmissions, between continents and countries. These cables serve as the primary means of international connectivity, enabling high-speed and reliable communication between regions separated by oceans.

Construction: Undersea cables are typically constructed by telecommunications companies or consortia of companies specializing in submarine cable systems. The cables consist of fiber optic strands encased in protective layers of insulation, armor, and waterproof materials. They are designed to withstand the harsh conditions of the marine environment, including pressure, temperature fluctuations, and potential damage from marine life or fishing activities.

Routing: Undersea cables follow specific routes determined by factors such as geographical proximity, navigational considerations, and economic viability. Cable routes are carefully planned to optimize connectivity between major population centers, economic hubs, and telecommunications exchange points. Advanced surveying techniques, including sonar mapping and seabed profiling, are used to identify suitable routes and avoid obstacles such as underwater mountains, trenches, and shipping lanes.

Capacity: Undersea cables have a significant capacity for transmitting data, with modern cables capable of carrying terabits or even petabits of data per second. The capacity of undersea cables is determined by factors such as the number of fiber strands, the type of fiber optic technology used (e.g., wavelength division multiplexing), and the signal amplification and regeneration equipment deployed along the cable route.

Landing Stations: Undersea cables terminate at landing stations located on the coastlines of different countries or territories. These landing stations serve as points of interconnection between the submarine cables and terrestrial telecommunications networks. They house the necessary equipment for signal amplification, signal processing, and data routing, allowing data traffic to be transmitted seamlessly between the undersea cables and the terrestrial infrastructure.

Global Connectivity: Undersea cables form a dense network of interconnected routes spanning the world's oceans, connecting continents and regions across the globe. This interconnected network enables global communication, international trade, financial transactions, and the exchange of information and ideas on a massive scale. Major undersea cable routes include transatlantic cables linking North America and Europe, transpacific cables connecting Asia and North America, and cables linking Africa, the Middle East, and Europe.

Challenges of UnderSea Cables

Physical Damage: Undersea cables are vulnerable to physical damage from natural disasters, human activities, and marine hazards. These can include ship anchors, fishing trawlers, seismic activity, underwater landslides, and ocean currents. Damage to the cable's protective armor or fiber optic strands can result in signal loss, reduced bandwidth, or complete cable failure, leading to network outages.

Anchor Drags: Ship anchors can accidentally drag along the seabed and snag undersea cables, causing them to rupture or become displaced. Anchor drags are a common cause of undersea cable damage, particularly in areas with heavy maritime traffic or near coastal regions where ships frequently anchor or moor.

Fishing Activities: Fishing trawlers and commercial fishing vessels pose a risk to undersea cables when their nets or fishing gear inadvertently snag on the cables during operations. Fishing-related incidents can damage or sever the cables, disrupting telecommunications connectivity and requiring costly repairs and cable maintenance efforts.

Natural Disasters: Undersea cables are susceptible to damage from natural disasters such as earthquakes, tsunamis, hurricanes, and underwater volcanic eruptions. These events can cause underwater disturbances, seabed shifts, and cable breaks, resulting in widespread network outages and communication disruptions in affected regions.

Cable Degradation: Over time, undersea cables may experience degradation due to factors such as corrosion, abrasion, and exposure to seawater. Cable degradation can degrade signal quality, increase transmission errors, and reduce the overall reliability and performance of the cable system. Regular maintenance and monitoring are required to detect and address cable degradation proactively.

Malicious Activities: Undersea cables are potential targets for sabotage, vandalism, or sabotage by malicious actors seeking to disrupt communications, espionage, or economic sabotage. Although rare, deliberate acts of cable sabotage can have significant consequences for regional or global telecommunications networks, necessitating enhanced security measures and surveillance to protect critical cable infrastructure.

Ways of Addressing the Challenges of UnderSea Cables

To address these challenges proactive measures are required:

Implementing cable protection measures

Deploying robust cable monitoring and maintenance systems

Establishing contingency plans for rapid response and cable repair in the event of outages or disruptions

Collaboration among cable operators, maritime authorities, and international organizations is essential to mitigate risks and ensure the resilience and reliability of undersea cable networks.

Factors to Consider When Comparing Satellite Connection (e.g Starlink) and Undersea Cable Connection

Speed:

Cable Connection: Cable connections typically offer high-speed broadband access, with download speeds ranging from tens to hundreds of megabits per second (Mbps) or even gigabit speeds in some areas.

Satellite Connection (e.g., Starlink): Satellite connections like Starlink can provide high-speed Internet access, but the speeds may vary depending on factors such as satellite coverage, network congestion, and atmospheric conditions. Starlink promises speeds of up to several hundred megabits per second (Mbps).

Latency:

Cable Connection: Cable connections generally have low latency, typically ranging from 10 to 50 milliseconds (ms), making them suitable for real-time applications like online gaming and video conferencing.

Satellite Connection (e.g., Starlink): Satellite connections often have higher latency compared to cable due to the distance signals must travel between Earth and satellites in orbit. Latency for satellite connections like Starlink can range from 20 ms to over 100 ms, potentially impacting interactive applications that require low latency.

Coverage:

Cable Connection: Cable networks are typically deployed in densely populated areas and urban centers, offering widespread coverage in developed regions.

Satellite Connection (e.g., Starlink): Satellite connections have the advantage of offering coverage in remote or rural areas where terrestrial infrastructure like cable or fiber optics is not available or cost-prohibitive. Satellite connections can provide coverage in virtually any location with a clear view of the sky.

Reliability:

Cable Connection: Cable connections are generally considered reliable, with minimal downtime and service interruptions in well-maintained networks.

Satellite Connection (e.g., Starlink): Satellite connections may be susceptible to disruptions due to factors such as atmospheric conditions (e.g., rain fade), satellite positioning, and network congestion. However, advancements in satellite technology and network design aim to improve reliability and minimize downtime.

Cost:

Cable Connection: Cable connections typically involve monthly subscription fees for Internet service, which can vary depending on factors such as speed tier, bundled services, and promotional offers.

Satellite Connection (e.g., Starlink): Satellite connections like Starlink may involve higher upfront costs for equipment such as satellite dishes and terminals. Additionally, monthly subscription fees may apply, although pricing models and subscription plans may vary.

Environmental Impact:

Cable Connection: Cable connections have minimal direct environmental impact, as they rely on terrestrial infrastructure like fiber optics and coaxial cables.

Satellite Connection (e.g., Starlink): Satellite connections involve the deployment of satellites into orbit, which may have environmental implications such as space debris and orbital congestion. However, satellite technology can also provide connectivity to remote areas without the need for extensive terrestrial infrastructure, potentially reducing environmental impacts associated with terrestrial infrastructure development.

Routing

It plays a fundamental role in how the Internet works, including both cable and satellite connections. Routing refers to the process of forwarding data packets between networks to ensure that they reach their intended destinations efficiently and reliably. Here's how routing works in the context of cable connections and the Internet:

Packet Forwarding: When a user sends data over the Internet, such as accessing a website or sending an email, the data is divided into packets. Each packet contains information such as the destination IP address, source IP address, and payload (data being transmitted). These packets are then forwarded across multiple networks to reach their destination.

IP Routing: Internet Protocol (IP) is the fundamental protocol used for routing data packets across networks on the Internet. Each device connected to the Internet, whether it's a computer, smartphone, or server, is assigned a unique IP address. Routers, which are specialized networking devices, use IP routing algorithms to determine the best path for forwarding packets based on their destination IP addresses.

Routing Tables: Routers maintain routing tables, which contain information about the network topology and available paths to reach different IP destinations. These routing tables are updated dynamically through routing protocols such as Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) or Interior Gateway Protocols (IGPs) like OSPF (Open Shortest Path First) and IS-IS (Intermediate System to Intermediate System). Routing protocols exchange routing information between routers, allowing them to build and update their routing tables based on network conditions and topology changes.

Path Selection: When a router receives a packet, it consults its routing table to determine the best path for forwarding the packet to its destination. Routing decisions are based on factors such as the destination IP address, network policies, link costs, and routing protocol metrics. Routers use algorithms such as shortest path algorithms (e.g., Dijkstra's algorithm) or policy-based routing to select the optimal path among multiple available routes.

Internet Backbone: The Internet backbone consists of high-capacity fiber optic cables and network infrastructure that interconnects various Internet Service Providers (ISPs), data centers, and content delivery networks (CDNs) worldwide. These backbone networks form the core infrastructure of the Internet, carrying large volumes of traffic between different regions and continents.

Peering and Transit: ISPs and network operators establish peering and transit agreements to exchange traffic and interconnect their networks. Peering allows ISPs to exchange traffic directly without going through third-party networks, while transit involves paying for access to other networks to reach specific destinations. These agreements influence routing decisions and determine how traffic flows across the Internet.

IANA

The Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) is a key organization responsible for the global coordination of the Internet's unique identifiers, such as IP addresses, domain names, protocol parameters, and port numbers. Here's a breakdown of its functions and roles:

IP Address Allocation: IANA manages the allocation and assignment of IP addresses to Regional Internet Registries (RIRs). RIRs, in turn, allocate IP addresses to Internet Service Providers (ISPs) and other organizations within their respective regions.

Domain Name System (DNS): IANA oversees the allocation of top-level domain names (TLDs), such as .com, .org, .net, and country-code TLDs like .uk, .de, etc. It maintains the authoritative root zone file, which is essential for the proper functioning of the DNS.

Protocol Parameters: IANA maintains registries of protocol parameters, which include numbers, codes, and identifiers used by various Internet protocols such as TCP/IP, UDP, HTTP, FTP, and others. These parameters ensure interoperability and standardization across different network devices and software applications.

Port Numbers: IANA manages the allocation of port numbers used in TCP/IP networking. Port numbers facilitate the communication between different applications running on the Internet by specifying different endpoints for data transmission.

Standards Development Support: IANA provides support to various Internet standardization organizations such as the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) and the Internet Architecture Board (IAB) by managing registries and ensuring consistency in the assignment of identifiers and parameters.

IANA Stewardship Transition: In recent years, there has been a significant transition in the stewardship of IANA functions from the United States government to the global Internet community. This transition aimed to enhance the accountability, transparency, and inclusiveness of IANA's operations.

Regional Internet Registries (RIRs)

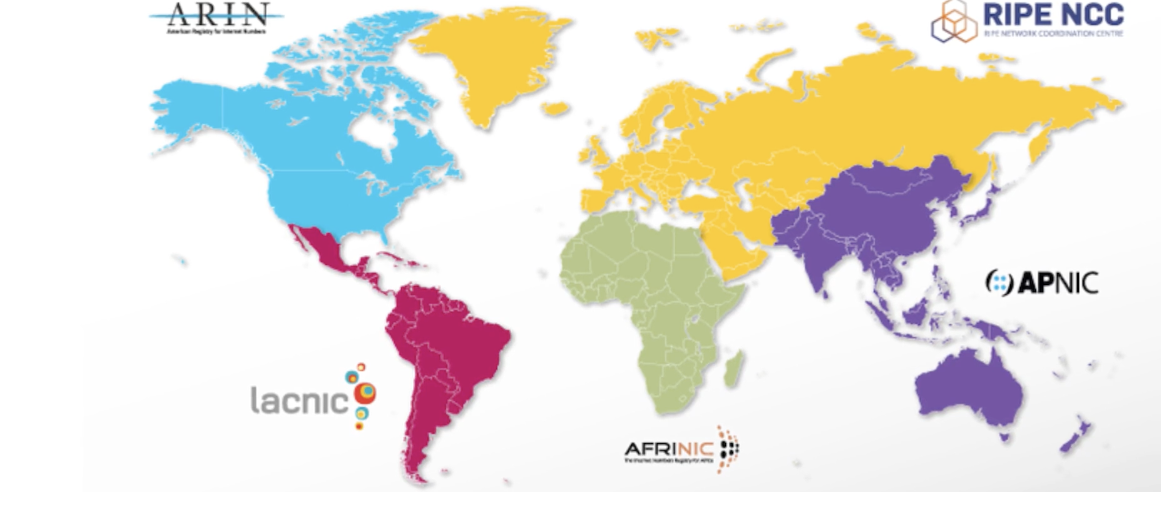

Under the coordination of the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA), IP address allocation is divided among Regional Internet Registries (RIRs). These RIRs manage the distribution and registration of IP addresses within their respective regions. As of my last update, there are five RIRs, each responsible for specific geographic regions:

American Registry for Internet Numbers (ARIN): ARIN serves the United States, Canada, and several Caribbean and North Atlantic islands. Its service region includes North America and parts of the Caribbean.

Réseaux IP Européens Network Coordination Centre (RIPE NCC): RIPE NCC serves Europe, the Middle East, and Central Asia. Its service region spans from Western Europe to parts of Central Asia.

Asia-Pacific Network Information Centre (APNIC): APNIC serves the Asia-Pacific region, covering East Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Oceania.

Latin America and Caribbean Network Information Centre (LACNIC): LACNIC serves Latin America and the Caribbean region.

African Network Information Centre (AfriNIC): AfriNIC serves the African continent.

Roles of RIRs apart from IP Address Allocation

Policy Development: RIRs facilitate the development of policies related to the allocation and management of IP address resources within their regions. These policies are typically developed through open and transparent community-driven processes, involving input from stakeholders such as ISPs, network operators, businesses, governments, and technical experts.

Training and Capacity Building: RIRs organize workshops, training programs, and conferences to educate network operators, policymakers, and other stakeholders about best practices in IP address management, network security, IPv6 deployment, and related topics. These capacity-building initiatives help strengthen the technical skills and knowledge base within their respective regions.

Resource Certification: RIRs offer resource certification services, such as Resource Public Key Infrastructure (RPKI), to help validate the authenticity and legitimacy of Internet number resources (e.g., IP address blocks and ASNs). Resource certification enhances the security and trustworthiness of routing information exchanged between autonomous systems on the Internet.

IPv6 Adoption and Deployment Support: RIRs actively promote the adoption and deployment of IPv6, the next-generation Internet protocol, which offers a larger address space and improved network scalability compared to IPv4. They provide technical assistance, resources, and advocacy efforts to encourage organizations to transition to IPv6 and ensure the continued growth of the Internet.

Community Engagement and Outreach: RIRs engage with their respective communities through mailing lists, forums, social media channels, and outreach events to gather feedback, address concerns, and foster collaboration on Internet governance issues, policy matters, and technical standards development.

Data Collection and Analysis: RIRs collect and analyze data on IP address utilization, allocation trends, Internet infrastructure developments, and related metrics to inform policy decisions, assess resource availability, and identify emerging challenges or opportunities in their regions.

Stakeholders that work with Afrinic in Kenya

AfriNIC serves the entire African continent as the Regional Internet Registry (RIR) responsible for the allocation and management of IP address resources within its service region and its headquarters is based in Mauritius.

However, AfriNIC does work with various stakeholders across Africa, including ISPs, network operators, government agencies, academic institutions, and civil society organizations, to support the effective utilization of Internet resources and promote Internet development in the region.

In Kenya specifically, there are local organizations, industry groups, and government agencies involved in Internet governance, policy development, and capacity-building initiatives related to Internet infrastructure and digital connectivity. These may include:

Communications Authority of Kenya (CA): The CA is the regulatory authority responsible for overseeing the telecommunications and broadcasting sectors in Kenya. It plays a key role in setting policies and regulations related to Internet infrastructure, spectrum management, and digital services.

Kenya Internet Exchange Point (KIXP): KIXP facilitates the exchange of Internet traffic within Kenya by providing a local peering platform where ISPs and network operators can interconnect and exchange data more efficiently. It helps improve Internet performance, reduce latency, and lower costs associated with international bandwidth.

Internet Society Kenya Chapter (ISOC Kenya): ISOC Kenya is a local chapter of the Internet Society (ISOC), a global nonprofit organization dedicated to promoting the open development, evolution, and use of the Internet. ISOC Kenya engages in advocacy, capacity building, and community outreach initiatives to support Internet access, digital literacy, and online rights in Kenya.

Kenya ICT Action Network (KICTANet): KICTANet is a multi-stakeholder platform that brings together individuals and organizations interested in ICT policy and regulation in Kenya. It facilitates discussions, knowledge sharing, and policy advocacy on a wide range of Internet governance issues, including cybersecurity, data protection, and access to information.

Internet Exchange Point (IXP)

An Internet Exchange Point (IXP) is a physical infrastructure that enables multiple Internet Service Providers (ISPs), content delivery networks (CDNs), and other network operators to exchange Internet traffic between their networks.

IXPs play a crucial role in improving the efficiency, performance, and cost-effectiveness of Internet connectivity by facilitating direct interconnection between networks at a single location.

How Internet Exchange Point works:

Traffic Exchange: At an IXP, participating networks connect their routers and switches to a shared Ethernet switch fabric. This allows them to exchange Internet traffic directly with each other, rather than routing traffic through upstream transit providers or relying on distant peering locations.

Reduced Latency: By exchanging traffic locally at an IXP, ISPs, and other network operators can reduce the latency (delay) associated with routing traffic over long distances. This results in faster response times for accessing online services and improved overall Internet performance for end-users.

Lower Costs: Directly exchanging traffic at an IXP can help reduce the need for expensive long-haul transit and peering agreements with upstream providers. This can lead to cost savings for participating networks, particularly for ISPs that have high volumes of inter-network traffic.

Improved Resilience: IXPs enhance the resilience and robustness of the Internet by providing alternative paths for data exchange. In the event of network outages or congestion on upstream links, traffic can be rerouted through IXPs, helping to maintain connectivity and prevent disruptions to Internet services.

Local Content Distribution: IXPs facilitate the distribution of locally hosted content, such as websites, streaming media, and cloud services, by enabling direct peering between content providers and ISPs. This reduces the need to fetch content from distant servers, leading to faster access times and lower bandwidth costs.

Promotion of Internet Ecosystem: By bringing together ISPs, content providers, CDNs, and other stakeholders, IXPs foster collaboration, innovation, and the growth of the local Internet ecosystem. They provide a neutral platform for exchanging ideas, sharing best practices, and developing new services and applications.

Automated Systems

It is a system like Google that gives identifier inform of IP addresses, ease of tracing

Role and Key Aspects of Automated Systems in Making IXP work effectively

Automated systems in the context of IXPs refer to the use of software-based tools and processes to automate various tasks related to the operation, management, and optimization of the IXP infrastructure and services.

These automated systems streamline operations, improve efficiency, and enhance the overall performance and reliability of the IXP. Here are some key aspects of automated systems in IXPs:

Member Onboarding: Automated systems facilitate the onboarding process for new members joining the IXP. They handle membership applications, eligibility verification, and provisioning of network connections, accelerating the onboarding process and ensuring compliance with IXP policies.

Configuration Management: Automated systems manage and configure the network infrastructure at the IXP, including routers, switches, and other networking devices. They automate tasks such as VLAN configuration, route optimization, and Quality of Service (QoS) settings, ensuring efficient use of network resources and optimal traffic routing.

Traffic Monitoring and Analysis: Automated monitoring tools continuously monitor network traffic flows at the IXP, collecting real-time data on bandwidth utilization, latency, and packet loss. They analyze traffic patterns, detect anomalies, and optimize network capacity and peering arrangements, enabling proactive network management and troubleshooting.

Billing and Accounting: Automated billing systems track usage and calculate fees for member organizations based on their traffic volume or port capacity. They generate invoices, process payments, and provide financial reports, streamlining the billing process and ensuring accurate accounting of services rendered.

Security and Access Control: Automated systems enforce security policies and access controls to protect the IXP infrastructure from unauthorized access and malicious activities. They implement authentication mechanisms, firewall rules, and intrusion detection/prevention systems (IDS/IPS), ensuring compliance with security best practices and regulatory requirements.

Remote Peering and Interconnection: Automated systems enable remote peering and interconnection between IXPs located in different geographic regions. They provision and configure remote peering connections, allowing network operators to extend their reach and access diverse connectivity options without physical presence at multiple IXPs.

Public and Private IP Address Assigned by IANA & RIRs

Public and private IP addresses are essential concepts in networking, particularly concerning the allocation and management of IP addresses by organizations like the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) and Regional Internet Registries (RIRs).

Public IP Addresses:

Public IP addresses are globally unique addresses assigned to devices connected to the Internet. They are routable on the public Internet and are used for communication between devices across different networks.

Public IP addresses are allocated by organizations such as IANA to RIRs, which in turn assign them to Internet Service Providers (ISPs), enterprises, and other organizations. RIRs ensure that public IP addresses are distributed efficiently and according to established allocation policies.

Public IP addresses are typically used for servers, routers, and devices that need to be accessible from the Internet, such as web servers, email servers, and public-facing services.

Private IP Addresses:

Private IP addresses are reserved for use within private networks, such as local area networks (LANs) or enterprise networks. They are not routable on the public Internet and are meant for communication within a specific network or organization.

Private IP address ranges are defined by Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) standards such as RFC 1918. The most commonly used private IP address ranges are:

10.0.0.0 to 10.255.255.255 (10.0.0.0/8)172.16.0.0 to 172.31.255.255 (172.16.0.0/12)192.168.0.0 to 192.168.255.255 (192.168.0.0/16)

Private IP addresses are used for devices within a private network to communicate with each other, share resources, and access the Internet through network address translation (NAT) devices. NAT translates private IP addresses to public IP addresses when communicating with external networks.

Automated Systems merge for Data Exchange and Interoperability between different Service Providers/Servers

Automated systems of different service providers can merge together through various mechanisms and interfaces designed to enable interoperability and data exchange. Here are some ways automated systems of different service providers can merge together:

API Integration: Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) allow different automated systems to communicate and exchange data with each other in a standardized and programmable manner. Service providers can develop APIs that expose specific functionalities and data from their systems, allowing other providers to integrate with them seamlessly. For example, an IXP's automated provisioning system could use APIs provided by member ISPs to automatically configure peering sessions and exchange traffic routing information.

Data Formats and Standards: Standardized data formats and protocols facilitate interoperability between automated systems. Service providers can agree upon common formats for exchanging information, such as JSON or XML, and adhere to industry standards and protocols relevant to their domain. This ensures that data exchanged between systems is structured and compatible, enabling smooth integration and data synchronization.

Middleware Solutions: Middleware platforms and integration tools provide middleware layers that act as intermediaries between different automated systems. These platforms can translate data formats, orchestrate business processes, and manage communication between systems, enabling seamless integration without requiring direct point-to-point connections. Middleware solutions often provide connectors or adapters for popular systems and protocols, simplifying integration efforts.

Enterprise Service Bus (ESB): An Enterprise Service Bus (ESB) is a software architecture that facilitates communication and integration between different applications and systems within an enterprise or across organizations. ESBs provide a centralized hub for routing messages, transforming data, and managing interactions between automated systems. Service providers can leverage ESBs to integrate their systems with those of other providers in a scalable and flexible manner.

Data Exchange Platforms: Data exchange platforms serve as centralized repositories or hubs for sharing and exchanging data between multiple parties. These platforms often provide standardized APIs, data transformation capabilities, and governance mechanisms to ensure secure and compliant data exchange. Service providers can leverage data exchange platforms to collaborate with other providers and merge their automated systems seamlessly.

Federated Identity and Access Management: Federated identity and access management systems enable users to access resources and services across multiple domains using a single set of credentials. Service providers can integrate their identity and access management systems with those of other providers, allowing seamless authentication and authorization for users accessing shared resources and services.

How Trust Plays a Crucial Role in Various Aspects of Internet Operations:

Peering Relationships: Internet Service Providers (ISPs) and network operators rely on trust when establishing peering relationships with one another. Peering agreements involve the mutual exchange of traffic between networks without financial compensation. Trust is essential in these arrangements because ISPs must believe that their peers will uphold their end of the agreement by delivering traffic reliably and without discrimination.

Data Transmission: Trust is vital in ensuring the integrity and confidentiality of data transmitted over the Internet. Server owners and service providers must trust the underlying network infrastructure to deliver data packets accurately and securely to their intended destinations. Encryption technologies and secure communication protocols help establish trust by protecting data from unauthorized access and interception during transmission.

Resource Allocation: Trust is necessary in the allocation and management of Internet resources, such as IP addresses and domain names. Organizations like the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) and Regional Internet Registries (RIRs) oversee the distribution of these resources based on established policies and procedures. Server owners and service providers trust these entities to allocate resources fairly and efficiently to ensure the stability and growth of the Internet.

Cybersecurity: Trust is critical in cybersecurity to protect against malicious activities such as hacking, malware, and data breaches. Server owners and service providers must trust the security measures implemented by their network infrastructure, software applications, and third-party service providers to safeguard their systems and data from cyber threats. Collaboration and information sharing among trusted partners help enhance cybersecurity posture and mitigate risks effectively.

Interoperability: Trust enables interoperability between different systems, platforms, and devices connected to the Internet. Server owners and service providers trust that products and services developed by third-party vendors adhere to industry standards, protocols, and specifications, ensuring compatibility and seamless integration within the broader Internet ecosystem.

Identified IXPs in Kenya

In Kenya, there are several Internet Exchange Points (IXPs) that play a crucial role in facilitating the exchange of Internet traffic within the country and the broader East African region. Some of the identified IXPs in Kenya include:

Kenya Internet Exchange Point (KIXP): KIXP is the primary Internet Exchange Point in Kenya, operated by the Telecommunications Service Providers Association of Kenya (TESPOK). It serves as a neutral peering platform where ISPs, content providers, and other network operators exchange Internet traffic locally, improving network performance and reducing latency.

Mombasa Internet Exchange Point (Mombasa IXP): Located in the coastal city of Mombasa, Mombasa IXP serves as a regional peering hub for Internet traffic exchange in East Africa. It complements KIXP by providing connectivity options for networks located in the coastal region and facilitating international connectivity through submarine cable landing stations.

Nairobi Internet Exchange Point (Nairobi IXP): Nairobi IXP is another exchange point located in the capital city of Nairobi, offering local peering and interconnection services to ISPs and network operators in the region. It contributes to improving Internet performance, enhancing network resilience, and promoting the growth of digital infrastructure in Nairobi and its surrounding areas.

Border Gateway Protocol

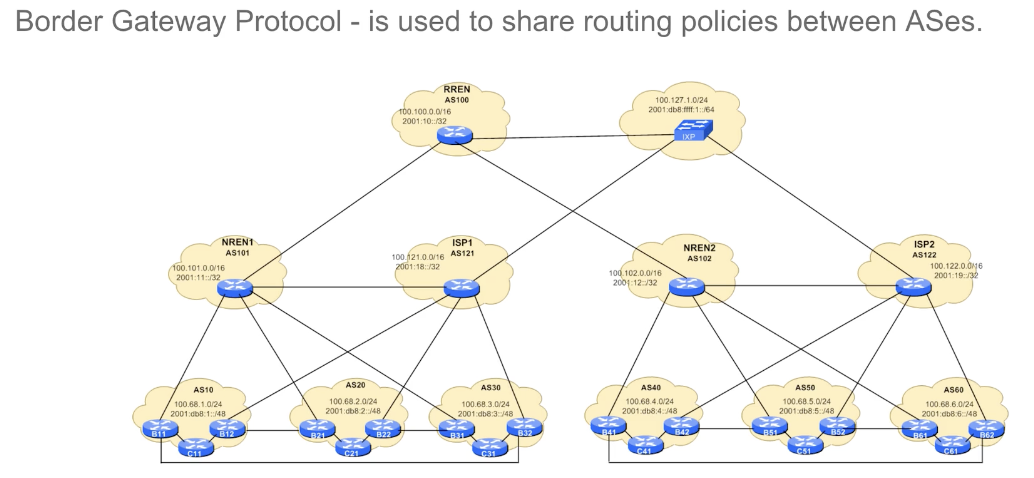

BGP is used to share routing policies between ASes

Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) is a crucial protocol that plays a central role in enabling communication between different networks on the Internet. BGP is the protocol used by Internet Service Providers (ISPs), network operators, and autonomous systems (ASes) to exchange routing information and make decisions about how to route traffic between different IP networks. Here's how BGP facilitates communication on the Internet:

Path Vector Protocol: BGP is a path vector protocol, which means it exchanges routing information between networks in the form of paths or routes. Each route contains information about the sequence of autonomous systems (ASes) that the traffic must traverse to reach its destination. BGP routers use this information to determine the best path for forwarding traffic based on policies and preferences configured by network administrators.

Dynamic Routing Updates: BGP routers exchange routing updates with their neighboring routers to inform them of reachable IP prefixes and the associated paths to reach those prefixes. These updates contain attributes such as the AS path, next-hop information, and route preferences. BGP routers use this information to construct a routing table that determines how to forward traffic towards its destination.

Path Selection and Policy Enforcement: BGP routers use various criteria to select the best path for forwarding traffic to a given destination. These criteria include the shortest AS path, the presence of specific route attributes, and configured policy settings. Network administrators can influence BGP route selection through the use of routing policies, route filters, and route manipulation techniques, allowing them to control traffic flows and optimize network performance.

Interdomain Routing: BGP is specifically designed for interdomain routing, which involves exchanging routing information between different autonomous systems (ASes) that operate independently and have their own administrative policies. BGP allows ISPs and network operators to establish peering relationships and exchange routing information to facilitate end-to-end communication between networks on the Internet.

Traffic Engineering and Load Balancing: BGP enables network operators to perform traffic engineering and load balancing by influencing the flow of traffic across multiple network paths. By manipulating BGP attributes such as the AS path, local preference, and MED (Multi-Exit Discriminator), network administrators can optimize traffic distribution, avoid network congestion, and improve overall network performance.

Challenges and Limitations of BCG

While Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) is a fundamental protocol for routing on the Internet, it's not without its challenges and limitations. One significant challenge is the potential for misconfigurations, errors, or malicious activities that can lead to routing problems, disruptions, and even security incidents. Here are some common challenges and incidents associated with BGP:

Route Leaks: Route leaks occur when an AS inadvertently announces routes learned from one provider to another provider or to the global Internet, causing traffic to be improperly redirected. This can lead to suboptimal routing, traffic congestion, and service disruptions.

BGP Hijacking: BGP hijacking occurs when an AS illegitimately announces IP prefixes that it does not own or control, causing traffic destined for those prefixes to be diverted to the hijacker's network. BGP hijacks can be accidental due to misconfigurations or intentional for malicious purposes such as eavesdropping, traffic interception, or denial of service attacks.

IP Prefix Hijacking: Similar to BGP hijacking, IP prefix hijacking involves an AS announcing IP prefixes that belong to another organization, leading to traffic redirection and potential security risks. High-profile incidents of IP prefix hijacking have occurred, including the hijacking of cryptocurrency-related IP prefixes for financial gain.

Political or Regulatory Manipulation: Governments or regulatory authorities may attempt to manipulate BGP routing to enforce censorship, block access to certain websites or online services, or control the flow of information. For example, in the case of Pakistan's attempt to block access to YouTube in 2008, the government inadvertently caused a global outage by hijacking YouTube's IP prefixes, disrupting access to the service worldwide.

Accidental Misconfigurations: BGP misconfigurations, such as incorrect route announcements, invalid route filters, or incomplete route propagation, can lead to unintended consequences, including routing loops, blackholing of traffic, and service outages. These misconfigurations may result from human errors, software bugs, or insufficient testing procedures.

Lack of Authentication and Security: BGP lacks built-in mechanisms for authentication and securing routing updates, making it vulnerable to various security threats such as route hijacking, route manipulation, and spoofing attacks. While efforts to enhance BGP security through mechanisms like Resource Public Key Infrastructure (RPKI) and BGPsec are underway, widespread adoption remains a challenge.

Addressing the Challenges of BGP

To address BGP's challenges we need measures to help mitigate the risks associated with BGP vulnerabilities and ensure the reliable operation of the global Internet:

collaboration among network operators, standards organizations, and policymakers to develop and deploy solutions that enhance the security, resilience, and stability of the Internet's routing infrastructure.

Measures such as:

improved BGP monitoring

validation of route announcements

route filtering

adoption of secure routing protocols

Thanks for reading through my article I give acknowledgement to ALTSchool Africa for the key areas covered in networking and ChatGPT for clear elaboration. We can connect more on X, LinkedIn, or have a one-on-one call on Mentorlst.

Subscribe to my newsletter

Read articles from J3bitok directly inside your inbox. Subscribe to the newsletter, and don't miss out.

Written by

J3bitok

J3bitok

Software Developer Learning Cloud and Cybersecurity Open for roles * If you're in the early stages of your career in software development (student or still looking for an entry-level role) and in need of mentorship you can book a session with me on Mentorlst.com.