PyTA Project: Depth-First Search for Control Flow Graph

Raine

RaineToday's task is to implement a function that takes a PythonTA control flow graph and returns all paths in the graph. In this article, I will first give an overview of modules related to control flow graph, and then provide an implementation of the function with depth-first search algorithm.

Running Control Flow Graph

A control flow graph (CFG) is a representation of different code blocks of a module and the different paths the blocks can be executed. A block in the CFG represents a list of code that can be executed consecutively. Whenever there is a "goto" type of statement that executes different blocks based on certain conditions (including if, while, for statement), the blocks are divided into different branches, forming multiple execution paths.

To run the control flow graph generator in PythonTA, we need to first install Graphviz (https://www.graphviz.org/download/), the software used to visualize the graphs, and make sure the link to the Graphviz executable is added to the PATH environment variable so that it can be found by PythonTA. For Windows, there is an option to add to PATH in the Graphviz installer, or we can manually add /your_absolute_path_to_graphviz/Graphviz/bin to the PATH variable.

After that, we can create a control flow graph of a given program with command python -m examples.sample_usage.draw_cfg <your-file.py>, as specified in the module examples/sample_usage/draw_cfg

import python_ta.cfg.cfg_generator as cfg_generator

USAGE = "USAGE: python -m examples.sample_usage.draw_cfg <your-file.py>"

def main(filepath: str) -> None:

cfg_generator.generate_cfg(mod=filepath, auto_open=True, visitor_options={

"separate-condition-blocks": True

})

if __name__ == "__main__":

import sys

if len(sys.argv) < 2:

print(USAGE)

exit(1)

Note that -m option is required to run the python program cfg_generator in order for the relative imports used in that program to work correctly. For the same reason, we cannot directly invoke generate_cfg() directly inside cfg_generator but can only invoke this function from outside.

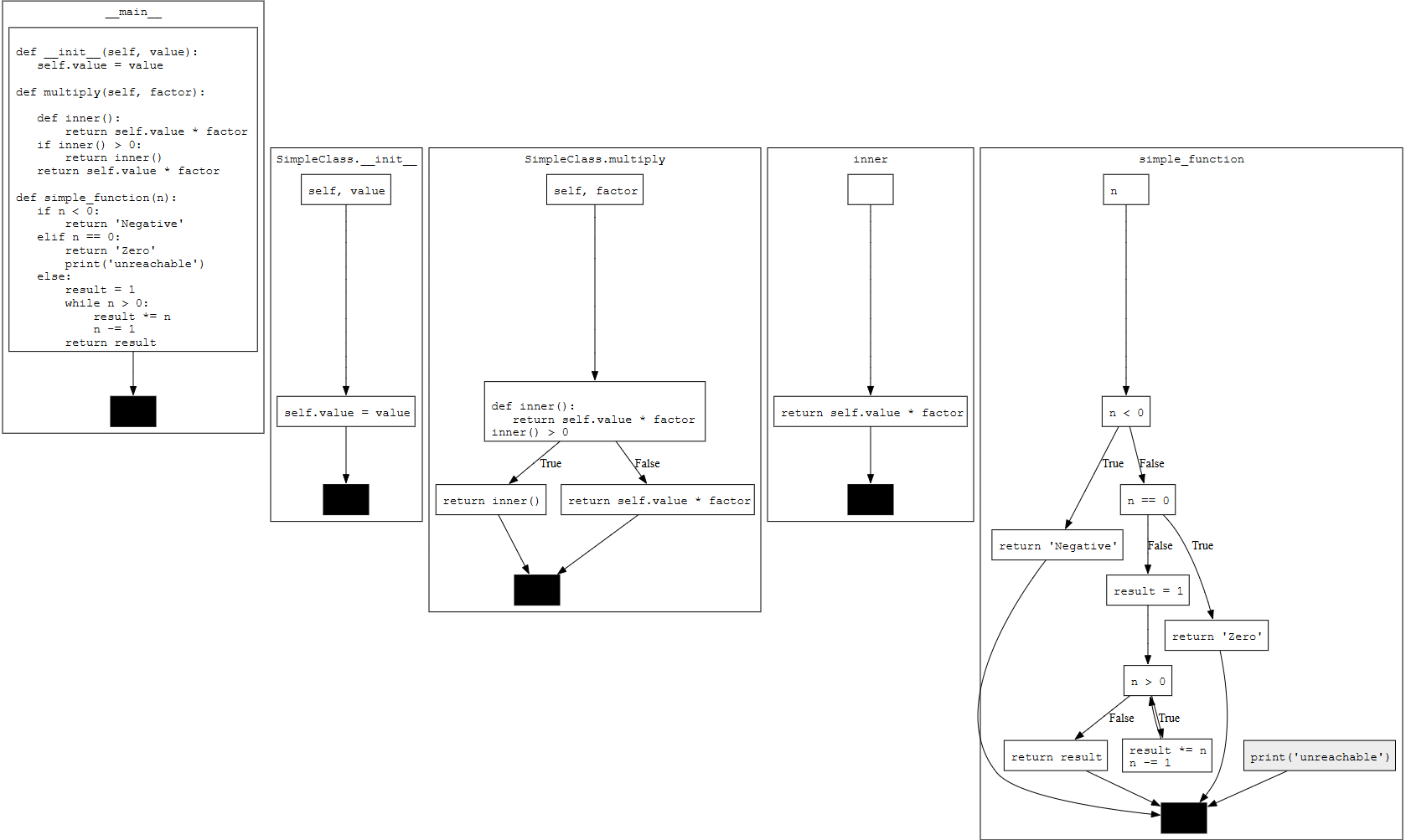

Here I created a example module for testing. Below are the module source code and corresponding CFG:

class SimpleClass:

def __init__(self, value):

self.value = value

def multiply(self, factor):

def inner():

return self.value * factor

if inner() > 0:

return inner()

return self.value * factor

def simple_function(n):

if n < 0:

return "Negative"

elif n == 0:

return "Zero"

print("unreachable")

else:

result = 1

while n > 0:

result *= n

n -= 1

return result

In the control flow graph, we can notice that a distinct graph is drawn for each module and function. Each graph has a starting block (which is function parameters for function graphs) and a black block indicating the end of program. If statements and loops are represented as edges connecting different blocks. Unreachable statements, such as the print("unreachable") after a return statement, are marked as grey.

Source Code for Control Flow Graph

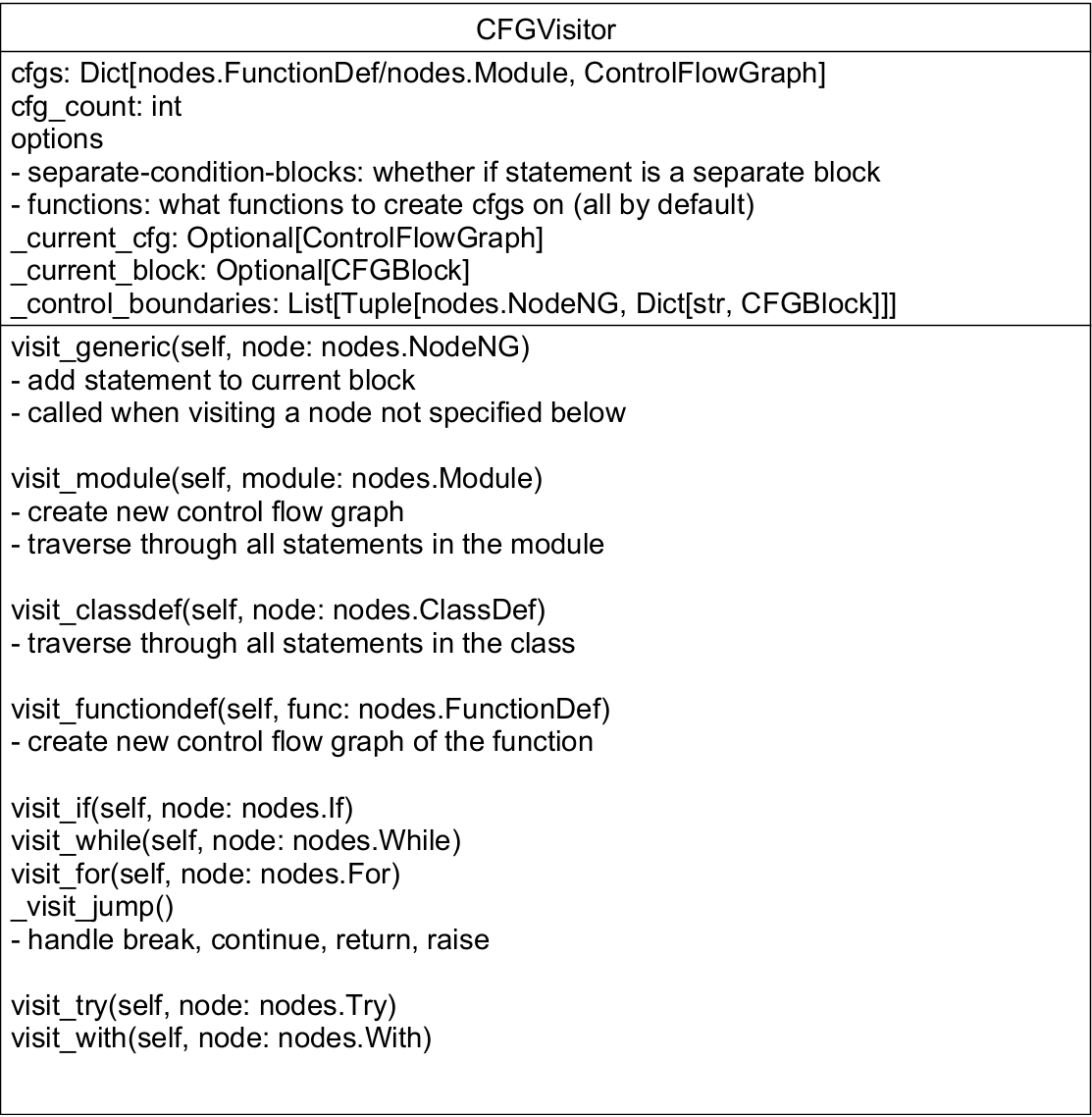

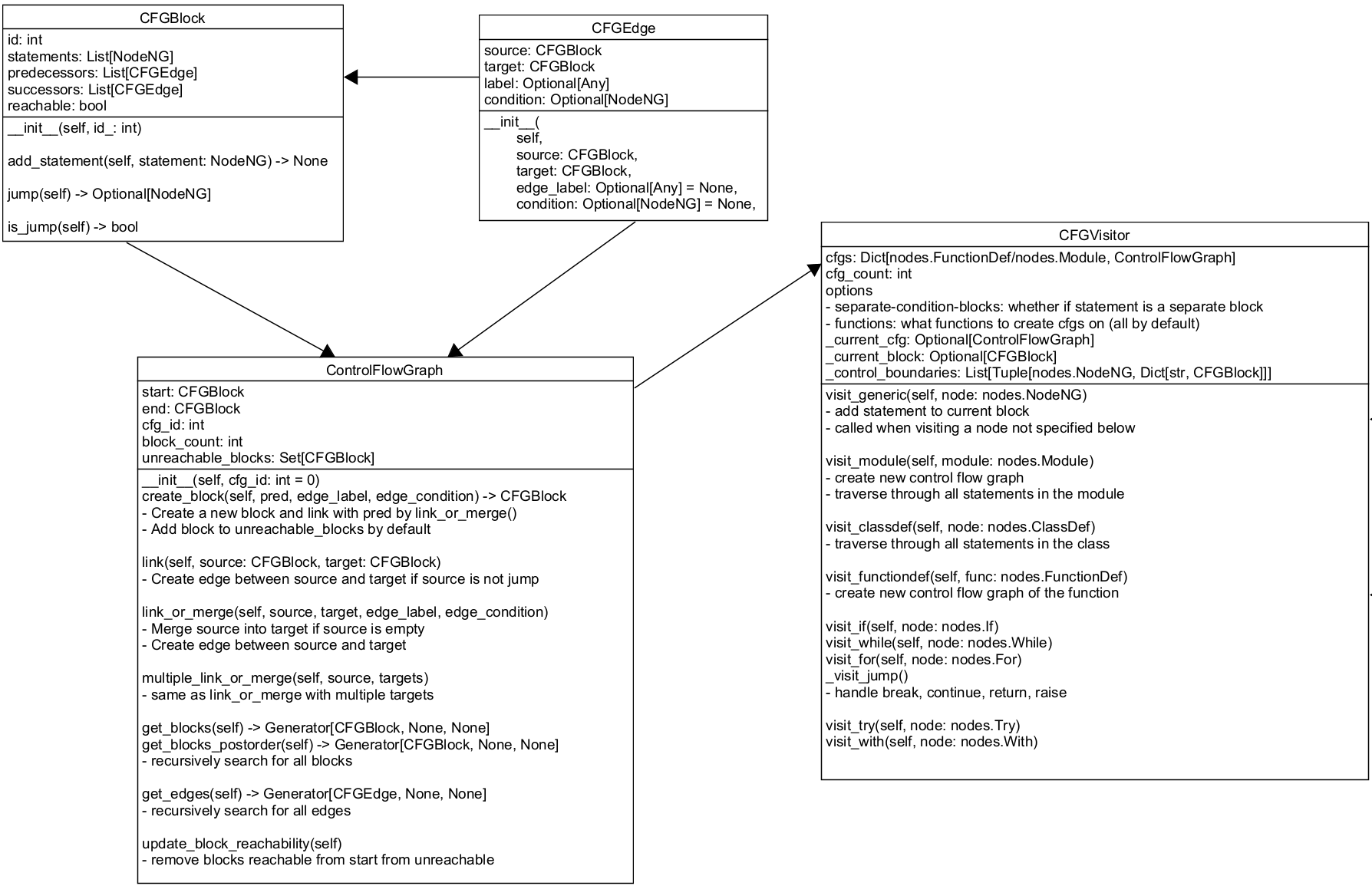

The implementation of control flow graph in PythonTA consists of three modules located under python_ta/cfg directory: graph.py, visitor.py, and cfg_generator.py. graph.py defines the CFG components, including code blocks, edges, and control flow graphs. visitor.py is used to construct a control flow graph from the abstract syntax tree of a program. cfg_generator.py invokes visitor to generate the control flow graph, and display the graph with Graphviz. In this section, I will provide a brief overview of graph.py and visitor.py module.

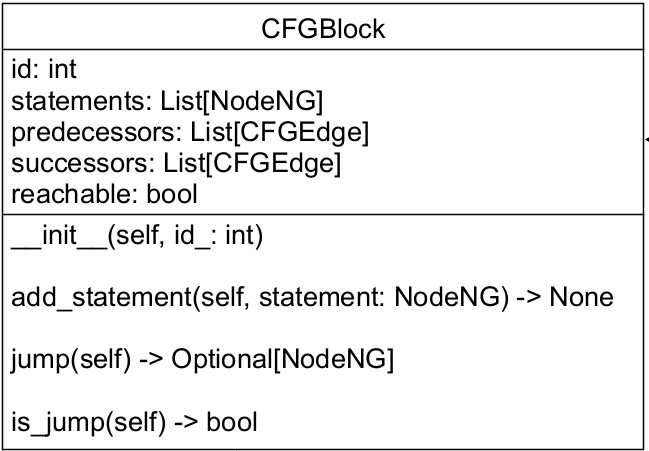

In graph.py , a single code block is represented as a CFGBlock object. It contains a unique id, a list of statements (stored as a list of astroid AST nodes) that are executed consecutively, a list of edges that connect to this node (predecessors) and a list of edges this node branches out (successors) (note that the CFG is a directed graph), and a boolean value indicating whether this block is reachable.

The add_statement() method is used to add an astroid node into statements. The block is "jump" when its last statement is one of break, continue, return, raise , statements that immediate ends this block and connects to the next block or end of function.

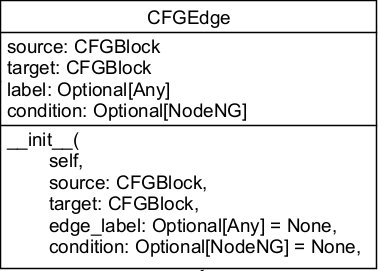

CFGEdge represents an edge between two blocks, whose direction is from source to target . The condition attribute is used to indicate True or False in if and while statements, and label is used for additional edge labeling.

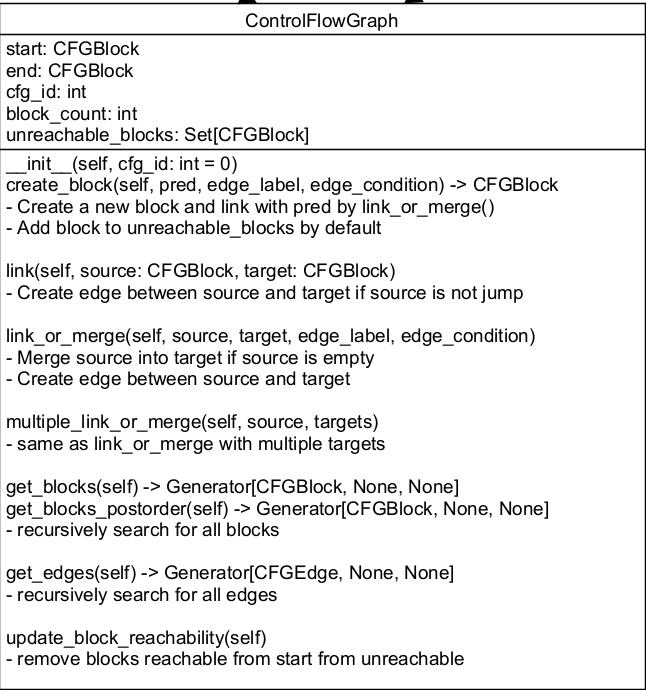

ControlFlowGraph class represents a complete control flow graph. It stores a start block, which is the first block of statements for a module or input parameters for a function, and end block marked in black. block_count is used to assign a unique id for each block, and cfg_id is the id for the control flow graph. unreachable_blocks stores a list of code blocks that are unreachable from the start of graph. Initially, every new block generated from create_block() is included in unreachable_blocks , and are updated only when update_block_reachability() is called at the end of CFG creation by the CFGVisitor, a mechanism similar to the mark-and-sweep garbage collection algorithm.

ControlFlowGraph provides various methods to construct edges between blocks. It also has get_blocks() and get_edges() methods that recursively search and return all (reachable) blocks and edges in the graph.

CFGVisitor class is used to construct control flow graphs frpom the abstract syntax tree of a Python module. It has two options seperate-condition-blocks, which determines whether the condition statement in a if statement or a loop is drawn as a separate block or as inside the previous block, and functions, which is a list of functions to draw graphs on. If functions is empty, graphs will be generated for every function in the module.

CFGVisitor works in a very similar way as pylint checkers (for more information, check out this previous post https://raineyang.hashnode.dev/pyta-project-implement-a-custom-pylint-checker-for-pythonta), except that inside its implementation, it needs to explicitly traverse through every statement in the AST. Here I will no go into details of how every visitor method is implemented specific, but here is a general overview:

visit_moduleandvisit_functiondefcreate new CFGs. In this program, a different CFG is created for every module or function.Statements that could lead to inconsecutive execution orders, including if, while, for, jump statements (break, continue, return, raise), try, with, are handle separately and are used to determine the graph structure.

Every other statements are merged into code blocks.

Here is a complete picture of different components of the control flow graph program:

Depth-First Search Algorithm

Now that we get familiar with the source code for control flow graph, it's time to complete our task: writing a program that returns all possible paths through the graph. To achieve this task, we can apply the depth-first search algorithm, a graph searching algorithm that goes to the farthest branches possible before backtracking. In DFS algorithm, the orders of nodes to be visited is maintained by a stack. Alternatively, we can used recursion to traverse nodes, since the order of recursion is internally maintained by the function call stack. In addition, we need to keep track of nodes that has already been visited to make sure that at each search every node is visited at most once. This is to prevent cycles, which, in our case, happens for while and for loops, in the graph that can lead to infinite loops.

Here's an implementation of DFS algorithm that returns the list of all paths in the graph. The nodes on the path are identified by their id. One thing to note about is the yield and yield from statements. These are similar to return statement, except that they only "temporarily" return the function while keeping the function local variables, including current_block and visited . yield statement returns a Generator that can be iterated through and lazily evaluates and returns its values.

Another part worth noting is the backtracking step in the algorithm. Since yield retains the internal states of the function, the same current_path and visited are being reused across all recursive calls. Thus, after we finish searching for one path and begins to search for another path, we need to remove the nodes recorded in current_path . visited also needs to be reset since the other paths may use common nodes as the current path.

def _dfs(current_block: CFGBlock, current_path: list[int], visited: set[int]):

"""

Perform a depth-first search on the CFG to find all paths from the start block to the end block.

"""

# Each block is visited at most once in one searching path

if current_block.id in visited:

return

visited.add(current_block.id)

current_path.append(current_block.id)

# base case: the current block is the end block or has no successors not being visited

if not current_block.successors or all([successor.target.id in visited for successor in current_block.successors]):

# return one found path

yield current_path.copy()

else:

# recursive case: visit all unvisited successors

for edge in current_block.successors:

# search through all sub-graphs

yield from _dfs(edge.target, current_path, visited)

# backtracking

current_path.pop()

visited.remove(current_block.id)

def find_all_paths(cfg: ControlFlowGraph) -> list[list[int]]:

"""

Find all paths from the start block to the end block in the given control flow graph.

"""

return list(_dfs(cfg.start, [], set()))

In addition to the algorithm itself, we also need a way to generate a control flow graph for testing. We can follow the same approach in the _generate() function in cfg_generate and implement the code below:

def create_cfg():

"""

Invoke CFG visitor to construct a control flow graph.

"""

# Generate a control flow graph for the given file

abs_path = os.path.abspath("test_class.py")

module = AstroidBuilder().file_build(abs_path)

visitor = CFGVisitor()

module.accept(visitor)

return visitor.cfgs

In create_cfg() , we first invoke Astroid API to convert the source code to an AST, and then apply the CFGVisitor to the AST through accept() method. This invokation structure is due to the use of visitor pattern in pylint. In the end, visitor.cfgs stores a dictionary whose keys are the module/function names and values are the corresponding CFGs.

Here's the complete code:

from python_ta.cfg.graph import CFGBlock, CFGEdge, ControlFlowGraph

from python_ta.cfg.visitor import CFGVisitor

import os

from astroid import nodes

from astroid.builder import AstroidBuilder

def _dfs(current_block: CFGBlock, current_path: list[int], visited: set[int]):

"""

Perform a depth-first search on the CFG to find all paths from the start block to the end block.

"""

# Each block is visited at most once in one searching path

if current_block.id in visited:

return

visited.add(current_block.id)

current_path.append(current_block.id)

# base case: the current block is the end block or has no successors not being visited

if not current_block.successors or all([successor.target.id in visited for successor in current_block.successors]):

# return one found path

yield current_path.copy()

else:

# recursive case: visit all unvisited successors

for edge in current_block.successors:

# search through all sub-graphs

yield from _dfs(edge.target, current_path, visited)

# backtracking

current_path.pop()

visited.remove(current_block.id)

def find_all_paths(cfg: ControlFlowGraph) -> list[list[int]]:

"""

Find all paths from the start block to the end block in the given control flow graph.

"""

return list(_dfs(cfg.start, [], set()))

def create_cfg():

"""

Invoke CFG visitor to construct a control flow graph.

"""

# Generate a control flow graph for the given file

abs_path = os.path.abspath("test_class.py")

module = AstroidBuilder().file_build(abs_path)

visitor = CFGVisitor()

module.accept(visitor)

return visitor.cfgs

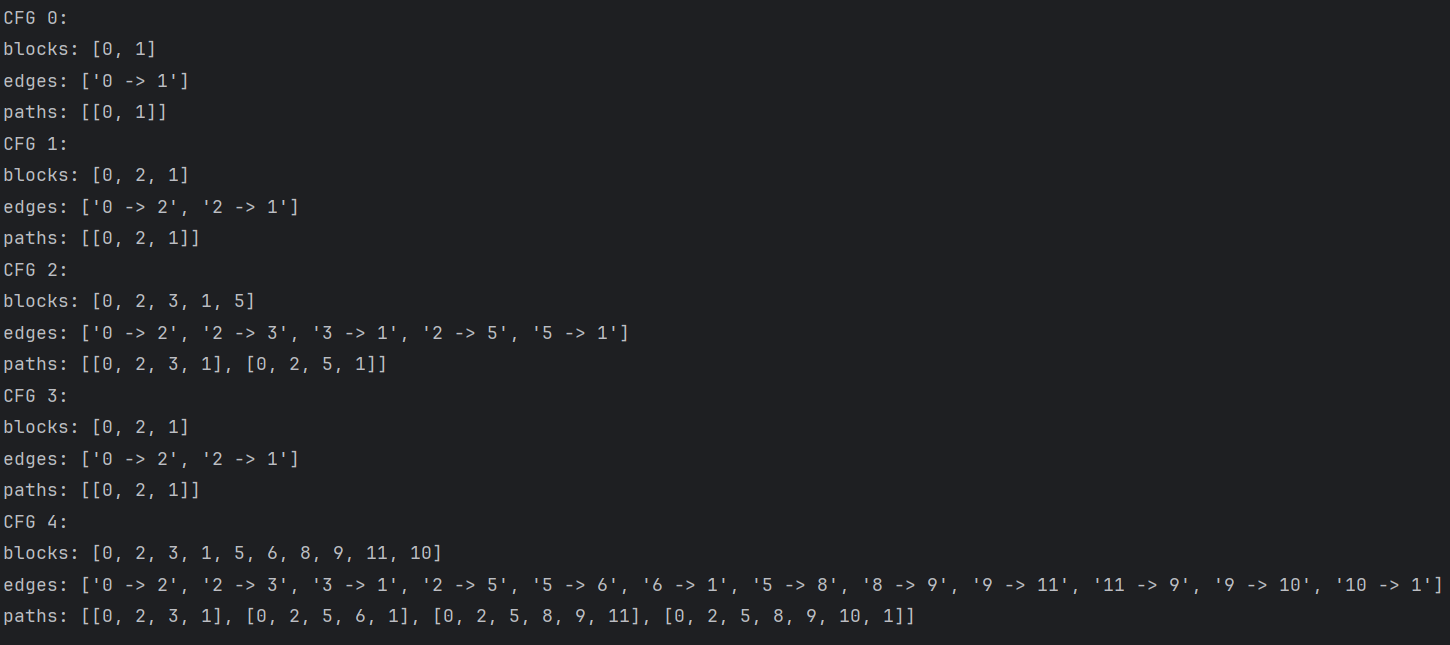

if __name__ == "__main__":

cfgs = create_cfg()

for cfg in cfgs.values():

print(f"CFG {cfg.cfg_id}:")

print(f"blocks: {[block.id for block in cfg.get_blocks()]}")

print("edges: " + str([f"{edge.source.id} -> {edge.target.id}" for edge in cfg.get_edges()]))

print(f"paths: {find_all_paths(cfg)}")

Subscribe to my newsletter

Read articles from Raine directly inside your inbox. Subscribe to the newsletter, and don't miss out.

Written by