From Stereotype to Reality: The Impact of Bias in AI Voice Assistants

Nityaa Kalra

Nityaa Kalra

In the previous post, we talked about historical roots of gender bias in AI voice assistants, tracing the trend back to the early days of telephone operators. While this historical context provides valuable insights, the question remains: how does this bias manifest in today's AI landscape?

If you’re a fan of The Big Bang Theory, you might recall Raj’s animated conversations with Siri, often treating her like a virtual girlfriend (S5 E14). That’s a rather exaggerated but illustrative example of how our relationships with voice assistants can sometimes blur the lines of human interaction.

A closer look at the phenomenon reveals that our preference for female voices in AI voice assistants is deeply ingrained. In an Interview, Professor Clifford Nass from Stanford University stated that preference to female voices starts early from the womb itself. He also said, “It’s much easier to find a female voice that everyone likes than a male voice that everyone likes.” Although this might be a case from perspective of the user, feminist theory objects to the way it reinforces the myth that women's voices are naturally calming and subservient.

This bias is evident in how we interact with technology. Female voices are automatically selected for the assistants whose duties entail merely ‘informing’. Majority of the navigation systems often default to female voices for exactly this reason. But, even this norm has its cracks. When BMW initially offered a female-voiced GPS, they didn’t anticipate the backlash and they had to revoke their female-voiced navigation system. Why? Only because some male drivers expressed discomfort in taking instructions from a female voice.

This is referred to as the 'Tightrope Effect', where individuals from marginalised communities are expected to adhere to social norms that have been pre-determined for them. In this case, it entails striking a balance between seeming knowledgeable and avoiding coming across as unduly pushy or authoritarian.

The allure of female voices might also be neurologically influenced. Studies suggest our brains respond more strongly to voices of the opposite gender, which could explain the over-representation of female voices, given the predominantly male workforce in tech development. Is it possible that this preference is simply a matter of familiarity or convenience? Or does it run deeper, reflecting ingrained gender roles and power dynamics? It’s a question worth exploring.

Power, Privilege, and Gender Norms in AI Design

The development of AI voice assistants is not just a technological process but also a socio-political one, deeply influenced by the power dynamics within the tech industry. These frequently show how some groups dominate the decision-making processes over others.

One significant factor is the unconscious bias inherent within the development teams. Anita Gurumurthy, the executive director of IT for Change, stated that “Individuals in privileged positions … lack the empiricism of lived experience.” This phenomenon is termed as 'Privilege Hazard' . It illustrates how individuals from privileged backgrounds may unintentionally perpetuate biases due to their limited exposure to diverse perspectives and lived realities.

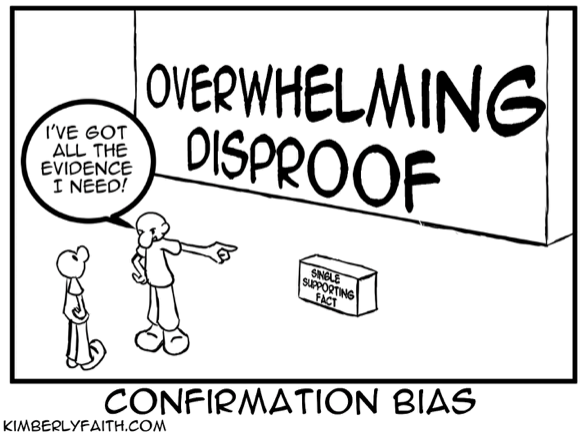

The historical precedent of women in supportive roles, such as telephone operators and secretaries, coupled with male-dominated design teams, has led to a default preference for female voices without fully analysing the broader societal ramifications, leading to a 'confirmation bias' where pre-existing beliefs about gender roles inadvertently influence decision-making. As a result, potential drawbacks of predominantly female voices and alternative options for AI assistants have been overlooked, perpetuating traditional gender stereotypes.

This prevalence of female voices in AI assistants has unfortunately opened the door to a disturbing trend: abuse and objectification. From catcalls to outright hostility, these voice assistants are subjected to a barrage of inappropriate behaviour. This behaviour not only reflects broader issues of gender bias but also raises ethical concerns about the treatment of digital entities designed to simulate human interaction. While adjustments such as implementing generic responses to abusive interactions have been made, they may not address the underlying societal attitudes that cause such behaviour. These are superficial fixes that deal with symptoms instead of the root cause.

To effectively tackle these issues, a broader approach needs to be adopted, one that advocates for larger societal shifts toward more fair and respectful attitudes, educates users, and challenges biases through design tactics.

The next post discusses recent advances in creating more inclusive, gender-neutral approaches along with their shortcomings.

References

C. Nass, Y. Moon, and N. Green, “Are machines gender neutral? Gender‐stereotypic responses to computers with voices,” J. Appl. Soc. Psychol., vol. 27, no. 10, pp. 864–876, 1997.

C. Nass and C. Yen, The man who lied to his laptop: What we can learn about ourselves from our machines. New York: Current, 2010.

“Tightrope bias,” Emtrain, 30-May-2023. [Online]. Available: https://emtrain.com/microlessons/tightrope-bias/

J. Junger et al., “Sex matters: Neural correlates of voice gender perception,” Neuroimage, vol. 79, pp. 275–287, 2013.

N. Ni Loideain and R. Adams, “From Alexa to Siri and the GDPR: The gendering of virtual personal assistants and the role of EU data protection law,” SSRN Electron. J., 2018.

C. ’ignazio and L. F. Klein, “Data feminism,” in The Power Chapter, MIT press, 2023, pp. 21–47.

M. E. Oswald and S. Grosjean, “Confirmation bias. Cognitive illusions: A handbook on fallacies and biases in thinking, judgment and memory,” vol. 79, 2004.

B. Green and S. Viljoen, “Algorithmic realism: expanding the boundaries of algorithmic thought,” in Proceedings of the 2020 conference on fairness, accountability, and transparency, 2020, pp. 19–31.

A. Elder, “Siri, stereotypes, and the mechanics of sexism,” Fem. Philos. Q., vol. 8, no. 3/4, 2022.

Subscribe to my newsletter

Read articles from Nityaa Kalra directly inside your inbox. Subscribe to the newsletter, and don't miss out.

Written by

Nityaa Kalra

Nityaa Kalra

I'm on a journey to become a data scientist with a focus on Natural Language Processing, Machine Learning, and Explainable AI. I'm constantly learning and an advocate for transparent and responsible AI solutions.