Verkle Tries Explained: A Simple Guide for Beginners

Rachit Srivastava

Rachit SrivastavaWelcome to a deep dive into Verkle trees and their impact on Ethereum's state management. As Ethereum aims to improve scalability and efficiency, Verkle trees are becoming a key part of the solution.

In this blog, we'll break down what Verkle trees are and how they compare to the traditional hexary Patricia trees. We'll discuss the upcoming changes that will introduce Verkle trees alongside the current hexary Patricia trees. After these changes, all state edits and copies of accessed state will be stored in the Verkle tree, while the hexary Patricia tree will be locked from further modifications. This marks the first step in moving Ethereum towards exclusively using Verkle trees for state storage. Let's explore the details and understand why this change is crucial for Ethereum's future.

Ethereum requires statelessness moving forward. Stateless clients are ones that do not have to store the entire state database in order to validate incoming blocks. Instead of using their own local copy of Ethereum's state to verify blocks, stateless clients use a "witness" to the state data that arrives with the block.

A witness is a collection of individual pieces of the state data that are required to execute a particular set of transactions, and a cryptographic proof that the witness is really part of the full data.

Currently, in a hexary Merkle tree, the witness sizes are huge.

State access proposed gas cost = 1900, and current gas limit = 30M. This implies a total of 15789 state accesses.

Using hexary merkle tree: 3kB per witness => ~47 MB!!!

Using binary Merkle tree: 0.5 kB/witness = 8 MB

Using width 256 verkle tree, 32 byte group: 96 byte/witness = 1.5 MB

Understanding Merkle Trees

A Merkle tree is a type of data structure used in computer science and cryptography to efficiently and securely verify large sets of data. It's particularly important in blockchain technologies, such as Bitcoin and Ethereum. Here’s how it works:

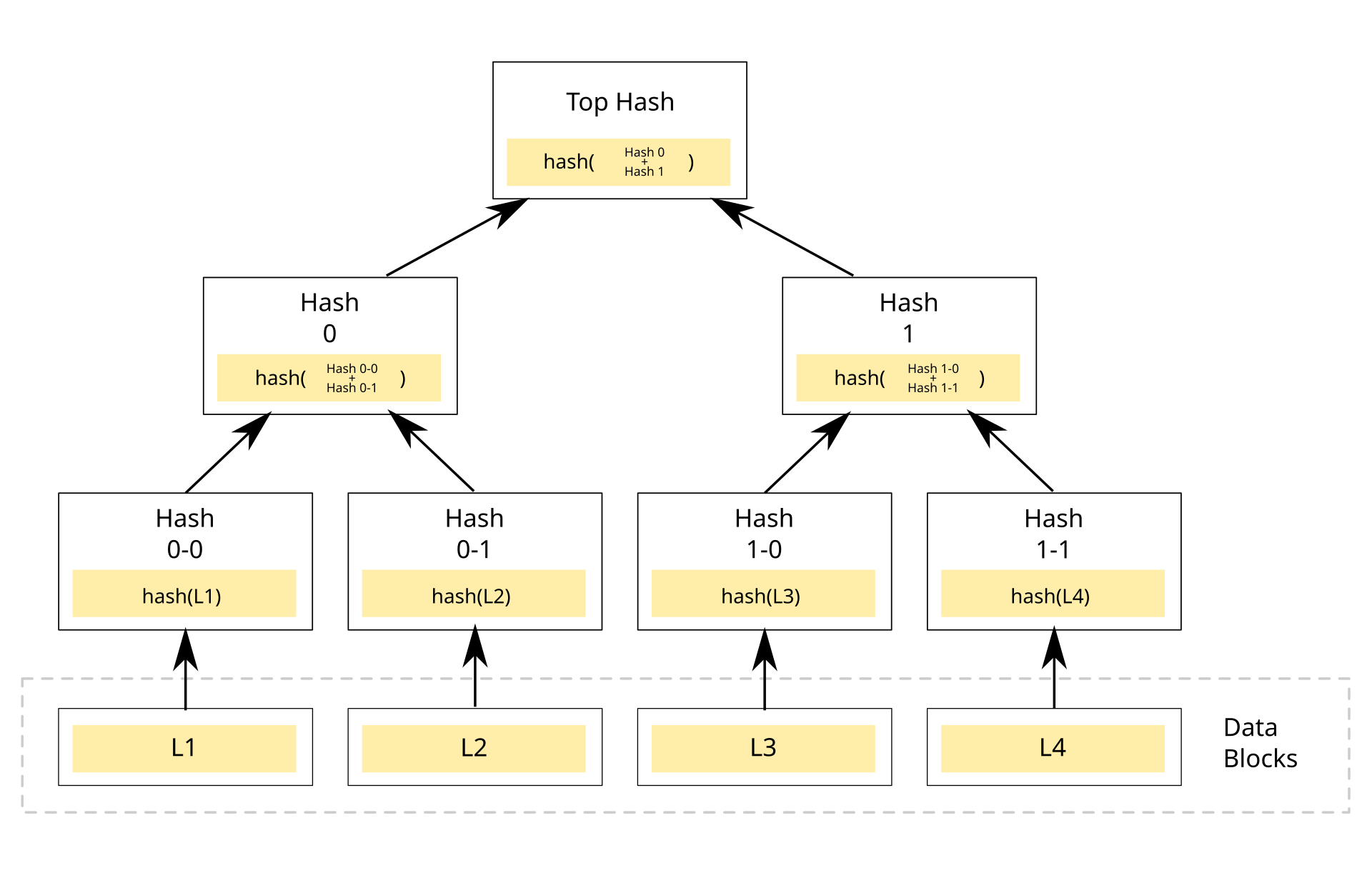

Structure of a Merkle Tree

Leaf Nodes: The bottom-most nodes in the tree are called leaf nodes. Each leaf node contains the hash of a piece of data (for example, a transaction in a blockchain).

Non-Leaf Nodes: Each non-leaf node is the hash of its two child nodes. This means that every node in the tree (except the leaves) is a hash of the data below it.

Root Hash: The top node of the tree is known as the root hash or Merkle root. This single hash represents the entire data set.

How it Works

Hashing: Hashing is the process of converting data into a fixed-size string of characters, which is typically a unique representation of the data. In a Merkle tree, the data in each leaf node is hashed.

Combining Hashes: Each pair of leaf node hashes is combined and then hashed again to form a parent node. This process is repeated up the tree until you reach the root hash.

Example

Imagine you have four transactions, A, B, C, and D. Here’s how you would create a Merkle tree:

Hash each transaction to create four leaf nodes:

Hash(A),Hash(B),Hash(C),Hash(D).Pair the leaf nodes and hash them to create the next level:

Hash(Hash(A) + Hash(B)),Hash(Hash(C) + Hash(D)).Finally, hash these results together to create the root hash:

Hash(Hash(Hash(A) + Hash(B)) + Hash(Hash(C) + Hash(D))).

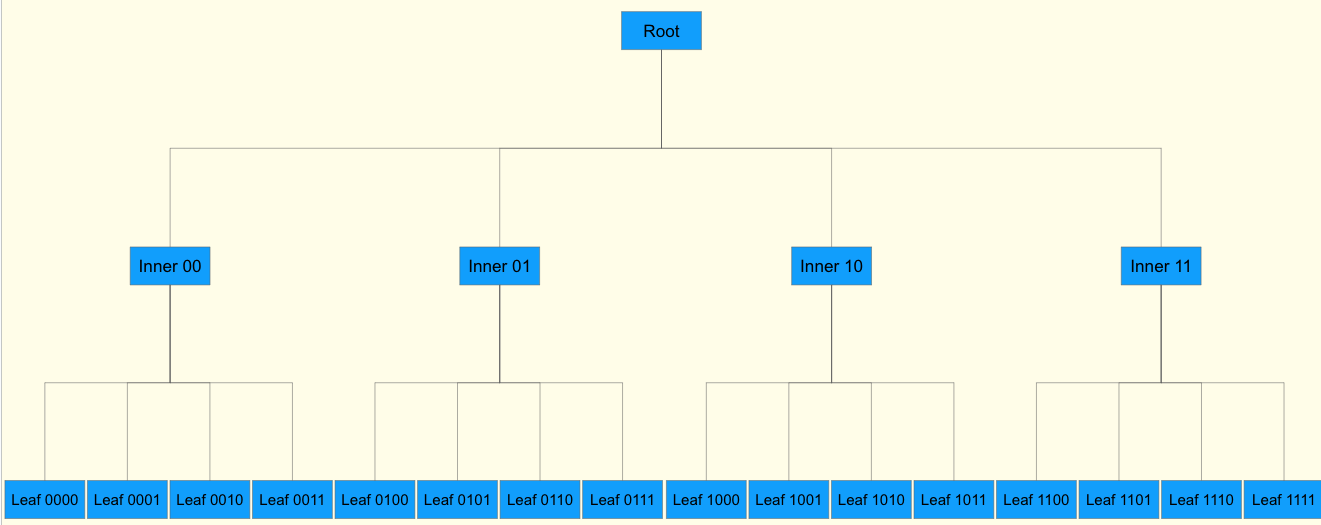

What if we increase the width of the merkle tree ?

In this case, to check a particular leaf, all siblings need to be passed to verify its inclusion inside

inner 01i.e. if there arennumber of leafs, to calculate the immediate hash, we need to providen-1number of leaf hashes.The proofs become very inefficient

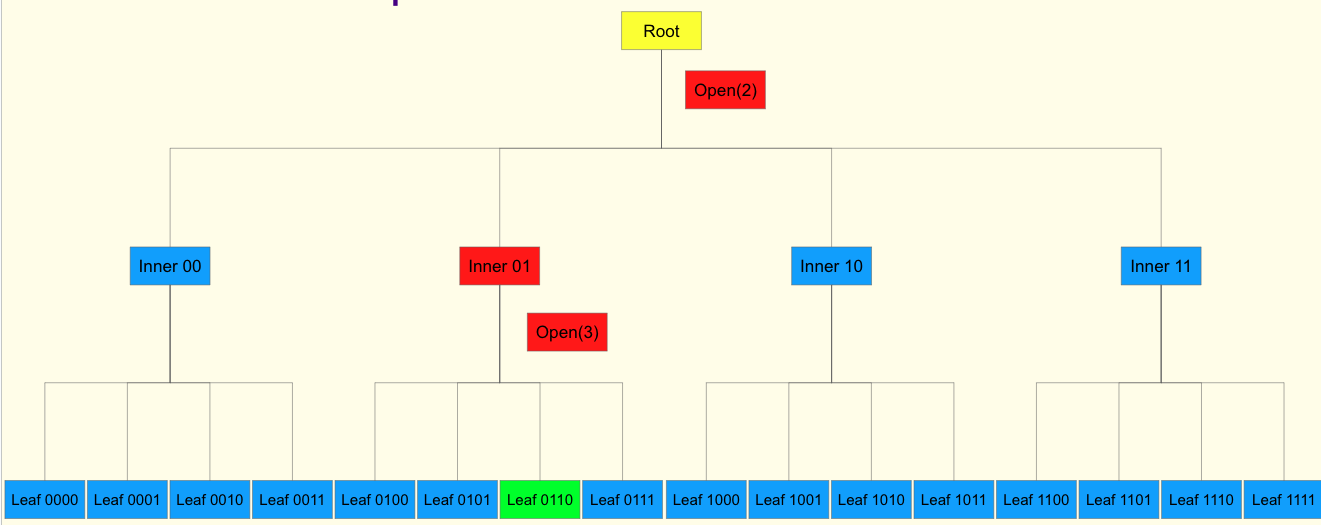

Where does Verkle trees come into play ?

The goal is to have a scheme where we can have less height of the tree and still are able to efficiently proof all siblings. We do this by introducing "Verkle Commitments" in the structure.

Verkle Trie

Verkle = Vector commitment + Merkle. Basically a merkle tree but with vector commitments instead of hashes.

Trie = tree + retrieval i.e. tree where each node represents a prefix of keys.

Understanding Vector Commitment Schemes

We will use KZG or Kate commitment scheme since its fairly more popular construction. In KZG we essentially create a polynomial, and then evaluate the polynomial at a secrete point. This is our vector commitment. The key is that using this commitment, we can do "openings" on the commitment and check the inclusion of a given set of points. You can read more about how this scheme works here.

Similarly another property of KZG is the ability to do multi proofs check. Essentially we can verify the inclusion of a set of point inside a KZG commited polynomial with a single pairing check. More info here.

From the above, it's easy to understand the advantages of a vector commitment over hash based commitment:

We can essentially "open" a vector commitment to verify the inclusion of a piece of data, contrary to hashed where we have to regenerate the hash itself, using all the involved data points. This reduced the size of our witness significantly.

Now, imagine the same tree before, but now nodes are a vector commitment rather than hash based commitments. This implies that to confirm the inclusion of a leaf, I need to do an opening check on the root, and similarly on the inner node, without having to supply all the siblings. Essentially reducing my witness size dramatically.

How to navigate:

Verkle proof for a single leaf: 0101 0111 1010 1111 -> 1213 is a key value pair.

We start from the root, the proof of Inner root A us

0101`.Proof that the root of Inner node B is the evaluation of the commitment of Inner node A at

0111.Proof that the root of the node

0101 0111 1010 111 -> 1213is the evaluation of the commitment of Inner node B at index 1010

Pedersen Commitment Scheme

The scheme involves:

Elliptic group G with generators \(g\_1, g\_2, ..., g\_n\\\).

The only important thing is that their relative discrete logarithm (\(g\_1=q∗g\_2\\\) is not known

This does not need a trusted setup

To commit to vector \(x\_1, x\_2, …, x\_n\\\)

- Compute \(C = x\_1 * g\_1 + x\_2 * g\_2 + ... + x\_n * g\_n\\\)Ethereum state after migration

Why Pederson commitment

Smaller commitments+proofs as no pairing-friendly group (32 bytes)

No trusted setup

Everything can be done inside a SNARK as well

Key Structure

\(key = Pederson(Contract Address, Storage Location[:-1]\\\) + suffix

where suffix = \(offset % 256\\\) ( offset in the group of 256 leaves )

- The key is called the

stem, which gives the pass through the stem tree and extension, and then we use suffix to get the element in the suffix tree.

State Expiry

Currently, once you pay fees on ethereum, the day stays forever. This causes state bloat after a while.

Now, after a while data will expire

Each year, a new period starts with a fresh tree

Data for the current and previous period is kept

Data of previous years is discarded ( except the root )

After two periods, data needs to be resurrected with a proof.

Address Space Extension

State expiry comes with a thing called Address Space Extension.

Currently in ethereum, address are 20 bytes long, which are the first 20 bytes of the hash of your public key.

Now the pub key will be 32 bytes. We take 26 bytes of the hash, the remaining 6 bytes are used for versioning and future use, and to denote the epoch / period.

| Period | Address | Balance |

| 0 | 010000000000000000...00000000 | 1234 |

| 0 | 010000000000000000...00000001 | 4567 |

| 1 | 0100000000010000000...0000000 | 7890 |

| 2 | 0100000000020000000...0000000 | 1121 |

| 2 | 0100000000000000000...0000000 | 1234 |

Period 0: Lets say Alice controls address 0x000...000. Bob has address 0x000.0001. Both have period as 0 since they are scene for the first time.

Period 1: Alice receives some funds from Bob, Bob doesn't actually resurrect the address from period 0 actually, but sends the funds to Alice to an address containing the current period ( 1 ). So it's seen for the first time in period 1. Alice still controls the private key of this hash, so in a way she controls two addresses with 1 private key.

Period 2: Alice wants the value from period one, she passes a proof to resurrect the address. The value from Period 1 that bob send, is not overwritten.

Points around Address State Extension:

Simplify data storage problem.

Risk of breaking existing contracts.

State Network

A network alongside the block propagation network.

A node only stores a subset of the entire data.

Data is requested over the network as needed

A proof is provided to ensure that the provided data is correct.

And that covers the whole design around Verkle trees.

Connect with on Twitter @privacy_prophet where I post deep insights on a wide variety of topics in the Blockchain ecosystem.

Resources

Subscribe to my newsletter

Read articles from Rachit Srivastava directly inside your inbox. Subscribe to the newsletter, and don't miss out.

Written by