Hugo vs Jekyll: an Epic Battle of Static Site Generator Themes

Victoria Drake

Victoria Drake

In this article, we'll compare the nuances of creating themes for the top two static site generators.

I recently took on the task of creating a documentation site theme for two projects. Both projects needed the same basic features, but one uses Jekyll while the other uses Hugo.

In typical developer rationality, there was clearly only one option. I decided to create the same theme in both frameworks, and to give you, dear reader, a side-by-side comparison.

This post isn’t a comprehensive theme-building guide, but is rather intended to familiarize you with the process of building a theme in either generator. Here's what we'll cover:

- How theme files are organized

- Where to put content

- How templating works

- Creating a top-level menu with the

pagesobject - Creating a menu with nested links from a data list

- Putting the template together

- Creating styles

- How to configure and deploy to GitHub Pages

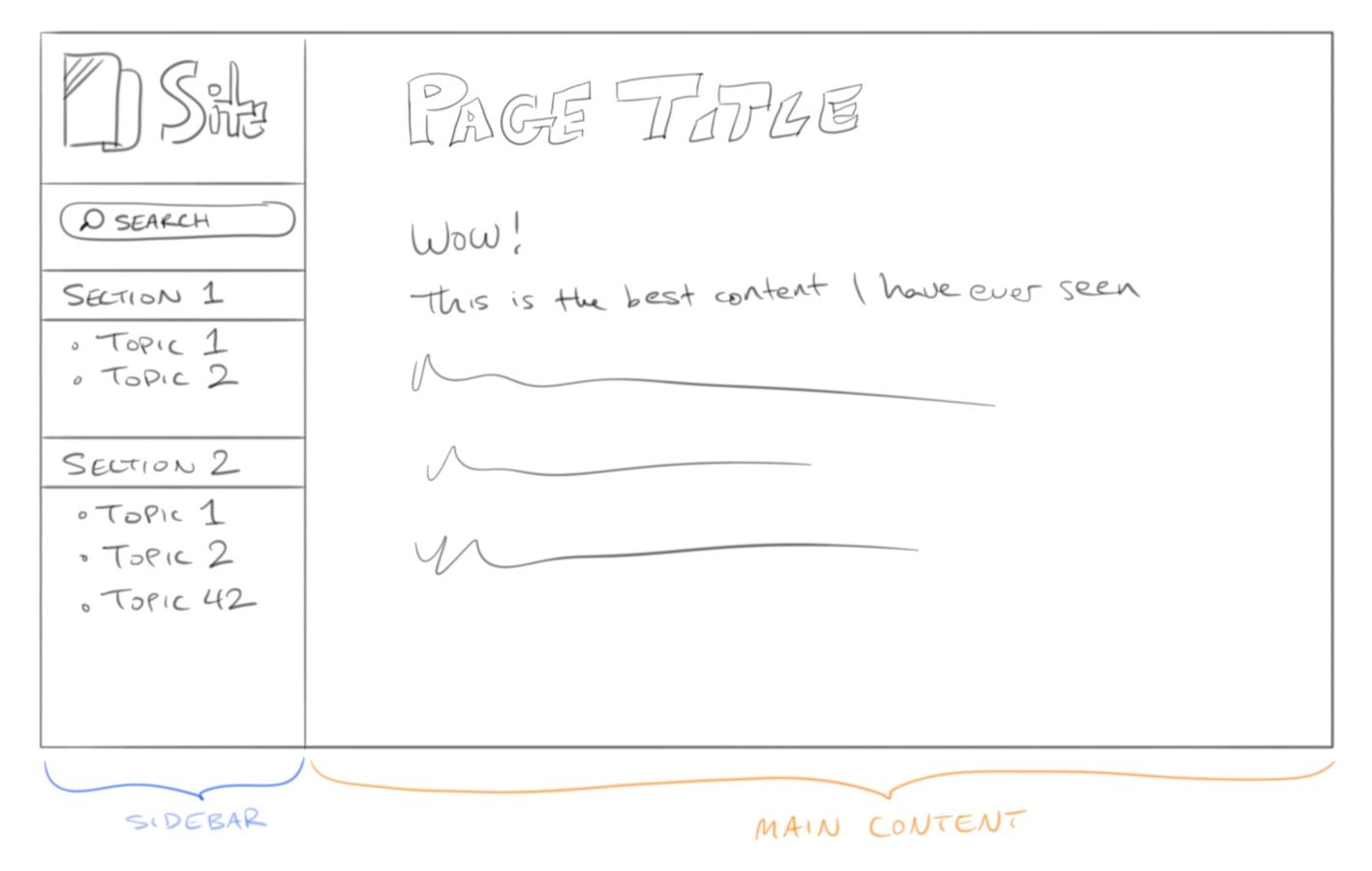

Here’s a crappy wireframe of the theme I’m going to create.

If you’re planning to build-along, it may be helpful to serve the theme locally as you build it – and both generators offer this functionality. For Jekyll, run jekyll serve, and for Hugo, hugo serve.

There are two main elements: the main content area, and the all-important sidebar menu. To create them, you’ll need template files that tell the site generator how to generate the HTML page. To organize theme template files in a sensible way, you first need to know what directory structure the site generator expects.

How theme files are organized

Jekyll supports gem-based themes, which users can install like any other Ruby gems. This method hides theme files in the gem, so for the purposes of this comparison, we aren’t using gem-based themes.

When you run jekyll new-theme <name>, Jekyll will scaffold a new theme for you. Here’s what those files look like:

.

├── assets

├── Gemfile

├── _includes

├── _layouts

│ ├── default.html

│ ├── page.html

│ └── post.html

├── LICENSE.txt

├── README.md

├── _sass

└── <name>.gemspec

The directory names are appropriately descriptive. The _includes directory is for small bits of code that you reuse in different places, in much the same way you’d put butter on everything. (Just me?)

The _layouts directory contains templates for different types of pages on your site. The _sass folder is for Sass files used to build your site’s stylesheet.

You can scaffold a new Hugo theme by running hugo new theme <name>. It has these files:

.

├── archetypes

│ └── default.md

├── layouts

│ ├── 404.html

│ ├── _default

│ │ ├── baseof.html

│ │ ├── list.html

│ │ └── single.html

│ ├── index.html

│ └── partials

│ ├── footer.html

│ ├── header.html

│ └── head.html

├── LICENSE

├── static

│ ├── css

│ └── js

└── theme.toml

You can see some similarities. Hugo’s page template files are tucked into layouts/. Note that the _default page type has files for a list.html and a single.html.

Unlike Jekyll, Hugo uses these specific file names to distinguish between list pages (like a page with links to all your blog posts on it) and single pages (like one of your blog posts). The layouts/partials/ directory contains the buttery reusable bits, and stylesheet files have a spot picked out in static/css/.

These directory structures aren’t set in stone, as both site generators allow some measure of customization. For example, Jekyll lets you define collections, and Hugo makes use of page bundles. These features let you organize your content multiple ways, but for now, let's look at where to put some simple pages.

Where to put content

To create a site menu that looks like this:

Introduction

Getting Started

Configuration

Deploying

Advanced Usage

All Configuration Settings

Customizing

Help and Support

You’ll need two sections (“Introduction” and “Advanced Usage”) containing their respective subsections.

Jekyll isn’t strict with its content location. It expects pages in the root of your site, and will build whatever’s there. Here’s how you might organize these pages in your Jekyll site root:

.

├── 404.html

├── assets

├── Gemfile

├── _includes

├── index.markdown

├── intro

│ ├── config.md

│ ├── deploy.md

│ ├── index.md

│ └── quickstart.md

├── _layouts

│ ├── default.html

│ ├── page.html

│ └── post.html

├── LICENSE.txt

├── README.md

├── _sass

├── <name>.gemspec

└── usage

├── customizing.md

├── index.md

├── settings.md

└── support.md

You can change the location of the site source in your Jekyll configuration.

In Hugo, all rendered content is expected in the content/ folder. This prevents Hugo from trying to render pages you don’t want, such as 404.html, as site content. Here’s how you might organize your content/ directory in Hugo:

.

├── _index.md

├── intro

│ ├── config.md

│ ├── deploy.md

│ ├── _index.md

│ └── quickstart.md

└── usage

├── customizing.md

├── _index.md

├── settings.md

└── support.md

To Hugo, _index.md and index.md mean different things. It can be helpful to know what kind of Page Bundle you want for each section: Leaf, which has no children, or Branch.

Now that you have some idea of where to put things, let’s look at how to build a page template.

How templating works

Jekyll page templates are built with the Liquid templating language. It uses braces to output variable content to a page, such as the page’s title: {{ page.title }}.

Hugo’s templates also use braces, but they’re built with Go Templates. The syntax is similar, but different: {{ .Title }}.

Both Liquid and Go Templates can handle logic. Liquid uses tags syntax to denote logic operations:

{% if user %}

Hello {{ user.name }}!

{% endif %}

And Go Templates places its functions and arguments in its braces syntax:

{{ if .User }}

Hello {{ .User }}!

{{ end }}

Templating languages allow you to build one skeleton HTML page, then tell the site generator to put variable content in areas you define. Let’s compare two possible default page templates for Jekyll and Hugo.

Jekyll’s scaffold default theme is bare, so we’ll look at their starter theme Minima. Here’s _layouts/default.html in Jekyll (Liquid):

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="{{ page.lang | default: site.lang | default: "en" }}">

{%- include head.html -%}

<body>

{%- include header.html -%}

<main class="page-content" aria-label="Content">

<div class="wrapper">

{{ content }}

</div>

</main>

{%- include footer.html -%}

</body>

</html>

Here’s Hugo’s scaffold theme layouts/_default/baseof.html (Go Templates):

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

{{- partial "head.html" . -}}

<body>

{{- partial "header.html" . -}}

<div id="content">

{{- block "main" . }}{{- end }}

</div>

{{- partial "footer.html" . -}}

</body>

</html>

Different syntax, same idea. Both templates pull in reusable bits for head.html, header.html, and footer.html. These show up on a lot of pages, so it makes sense not to have to repeat yourself.

Both templates also have a spot for the main content, though the Jekyll template uses a variable ({{ content }}) while Hugo uses a block ({{- block "main" . }}{{- end }}). Blocks are just another way Hugo lets you define reusable bits.

Now that you know how templating works, you can build the sidebar menu for the theme.

Creating a top-level menu with the pages object

You can programmatically create a top-level menu from your pages. It will look like this:

Introduction

Advanced Usage

Let’s start with Jekyll. You can display links to site pages in your Liquid template by iterating through the site.pages object that Jekyll provides and building a list:

<ul>

{% for page in site.pages %}

<li><a href="{{ page.url | absolute_url }}">{{ page.title }}</a></li>

{% endfor %}

</ul>

This returns all of the site’s pages, including all the ones that you might not want, like 404.html. You can filter for the pages you actually want with a couple more tags, such as conditionally including pages if they have a section: true parameter set:

<ul>

{% for page in site.pages %}

{%- if page.section -%}

<li><a href="{{ page.url | absolute_url }}">{{ page.title }}</a></li>

{%- endif -%}

{% endfor %}

</ul>

You can achieve the same effect with slightly less code in Hugo. Loop through Hugo’s .Pages object using Go Template’s range action:

<ul>

{{ range .Pages }}

<li>

<a href="{{.Permalink}}">{{.Title}}</a>

</li>

{{ end }}

</ul>

This template uses the .Pages object to return all the top-level pages in content/ of your Hugo site. Since Hugo uses a specific folder for the site content you want rendered, there’s no additional filtering necessary to build a simple menu of site pages.

Creating a menu with nested links from a data list

Both site generators can use a separately defined data list of links to render a menu in your template. This is more suitable for creating nested links, like this:

Introduction

Getting Started

Configuration

Deploying

Advanced Usage

All Configuration Settings

Customizing

Help and Support

Jekyll supports data files in a few formats, including YAML. Here’s the definition for the menu above in _data/menu.yml:

section:

- page: Introduction

url: /intro

subsection:

- page: Getting Started

url: /intro/quickstart

- page: Configuration

url: /intro/config

- page: Deploying

url: /intro/deploy

- page: Advanced Usage

url: /usage

subsection:

- page: Customizing

url: /usage/customizing

- page: All Configuration Settings

url: /usage/settings

- page: Help and Support

url: /usage/support

Here’s how to render the data in the sidebar template:

{% for a in site.data.menu.section %}

<a href="{{ a.url }}">{{ a.page }}</a>

<ul>

{% for b in a.subsection %}

<li><a href="{{ b.url }}">{{ b.page }}</a></li>

{% endfor %}

</ul>

{% endfor %}

This method allows you to build a custom menu, two nesting levels deep. The nesting levels are limited by the for loops in the template. For a recursive version that handles further levels of nesting, see Nested tree navigation with recursion.

Hugo does something similar with its menu templates. You can define menu links in your Hugo site config, and even add useful properties that Hugo understands, like weighting. Here’s a definition of the menu above in config.yaml:

sectionPagesMenu: main

menu:

main:

- identifier: intro

name: Introduction

url: /intro/

weight: 1

- name: Getting Started

parent: intro

url: /intro/quickstart/

weight: 1

- name: Configuration

parent: intro

url: /intro/config/

weight: 2

- name: Deploying

parent: intro

url: /intro/deploy/

weight: 3

- identifier: usage

name: Advanced Usage

url: /usage/

- name: Customizing

parent: usage

url: /usage/customizing/

weight: 2

- name: All Configuration Settings

parent: usage

url: /usage/settings/

weight: 1

- name: Help and Support

parent: usage

url: /usage/support/

weight: 3

Hugo uses the identifier, which must match the section name, along with the parent variable to handle nesting. Here’s how to render the menu in the sidebar template:

<ul>

{{ range .Site.Menus.main }}

{{ if .HasChildren }}

<li>

<a href="{{ .URL }}">{{ .Name }}</a>

</li>

<ul class="sub-menu">

{{ range .Children }}

<li>

<a href="{{ .URL }}">{{ .Name }}</a>

</li>

{{ end }}

</ul>

{{ else }}

<li>

<a href="{{ .URL }}">{{ .Name }}</a>

</li>

{{ end }}

{{ end }}

</ul>

The range function iterates over the menu data, and Hugo’s .Children variable handles nested pages for you.

Putting the template together

With your menu in your reusable sidebar bit (_includes/sidebar.html for Jekyll and partials/sidebar.html for Hugo), you can add it to the default.html template.

In Jekyll:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="{{ page.lang | default: site.lang | default: "en" }}">

{%- include head.html -%}

<body>

{%- include sidebar.html -%}

{%- include header.html -%}

<div id="content" class="page-content" aria-label="Content">

{{ content }}

</div>

{%- include footer.html -%}

</body>

</html>

In Hugo:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

{{- partial "head.html" . -}}

<body>

{{- partial "sidebar.html" . -}}

{{- partial "header.html" . -}}

<div id="content" class="page-content" aria-label="Content">

{{- block "main" . }}{{- end }}

</div>

{{- partial "footer.html" . -}}

</body>

</html>

When the site is generated, each page will contain all the code from your sidebar.html.

Create a stylesheet

Both site generators accept Sass for creating CSS stylesheets. Jekyll has Sass processing built in, and Hugo uses Hugo Pipes. Both options have some quirks.

Sass and CSS in Jekyll

To process a Sass file in Jekyll, create your style definitions in the _sass directory. For example, in a file at _sass/style-definitions.scss:

$background-color: #eef !default;

$text-color: #111 !default;

body {

background-color: $background-color;

color: $text-color;

}

Jekyll won’t generate this file directly, as it only processes files with front matter. To create the end-result filepath for your site’s stylesheet, use a placeholder with empty front matter where you want the .css file to appear. For example, assets/css/style.scss. In this file, simply import your styles:

---

---

@import "style-definitions";

This rather hackish configuration has an upside: you can use Liquid template tags and variables in your placeholder file. This is a nice way to allow users to set variables from the site _config.yml, for example.

The resulting CSS stylesheet in your generated site has the path /assets/css/style.css. You can link to it in your site’s head.html using:

<link rel="stylesheet" href="{{ "/assets/css/style.css" | relative_url }}" media="screen">

Sass and Hugo Pipes in Hugo

Hugo uses Hugo Pipes to process Sass to CSS. You can achieve this by using Hugo’s asset processing function, resources.ToCSS, which expects a source in the assets/ directory. It takes the SCSS file as an argument.

With your style definitions in a Sass file at assets/sass/style.scss, here’s how to get, process, and link your Sass in your theme’s head.html:

{{ $style := resources.Get "/sass/style.scss" | resources.ToCSS }}

<link rel="stylesheet" href="{{ $style.RelPermalink }}" media="screen">

Hugo asset processing requires extended Hugo, which you may not have by default. You can get extended Hugo from the releases page.

Configure and deploy to GitHub Pages

Before your site generator can build your site, it needs a configuration file to set some necessary parameters. Configuration files live in the site root directory. Among other settings, you can declare the name of the theme to use when building the site.

Configure Jekyll

Here’s a minimal _config.yml for Jekyll:

title: Your awesome title

description: >- # this means to ignore newlines until "baseurl:"

Write an awesome description for your new site here. You can edit this

line in _config.yml. It will appear in your document head meta (for

Google search results) and in your feed.xml site description.

baseurl: "" # the subpath of your site, e.g. /blog

url: "" # the base hostname & protocol for your site, e.g. http://example.com

theme: # for gem-based themes

remote_theme: # for themes hosted on GitHub, when used with GitHub Pages

With remote_theme, any Jekyll theme hosted on GitHub can be used with sites hosted on GitHub Pages.

Jekyll has a default configuration, so any parameters added to your configuration file will override the defaults. Here are additional configuration settings.

Configure Hugo

Here’s a minimal example of Hugo’s config.yml:

baseURL: https://example.com/ # The full domain your site will live at

languageCode: en-us

title: Hugo Docs Site

theme: # theme name

Hugo makes no assumptions, so if a necessary parameter is missing, you’ll see a warning when building or serving your site. Here are all configuration settings for Hugo.

Deploy to GitHub Pages

Both generators build your site with a command.

For Jekyll, use jekyll build. See further build options here.

For Hugo, use hugo. You can run hugo help or see further build options here.

You’ll have to choose the source for your GitHub Pages site. Once done, your site will update each time you push a new build. Of course, you can also automate your GitHub Pages build using GitHub Actions. Here’s one for building and deploying with Hugo, and one for building and deploying Jekyll.

Showtime!

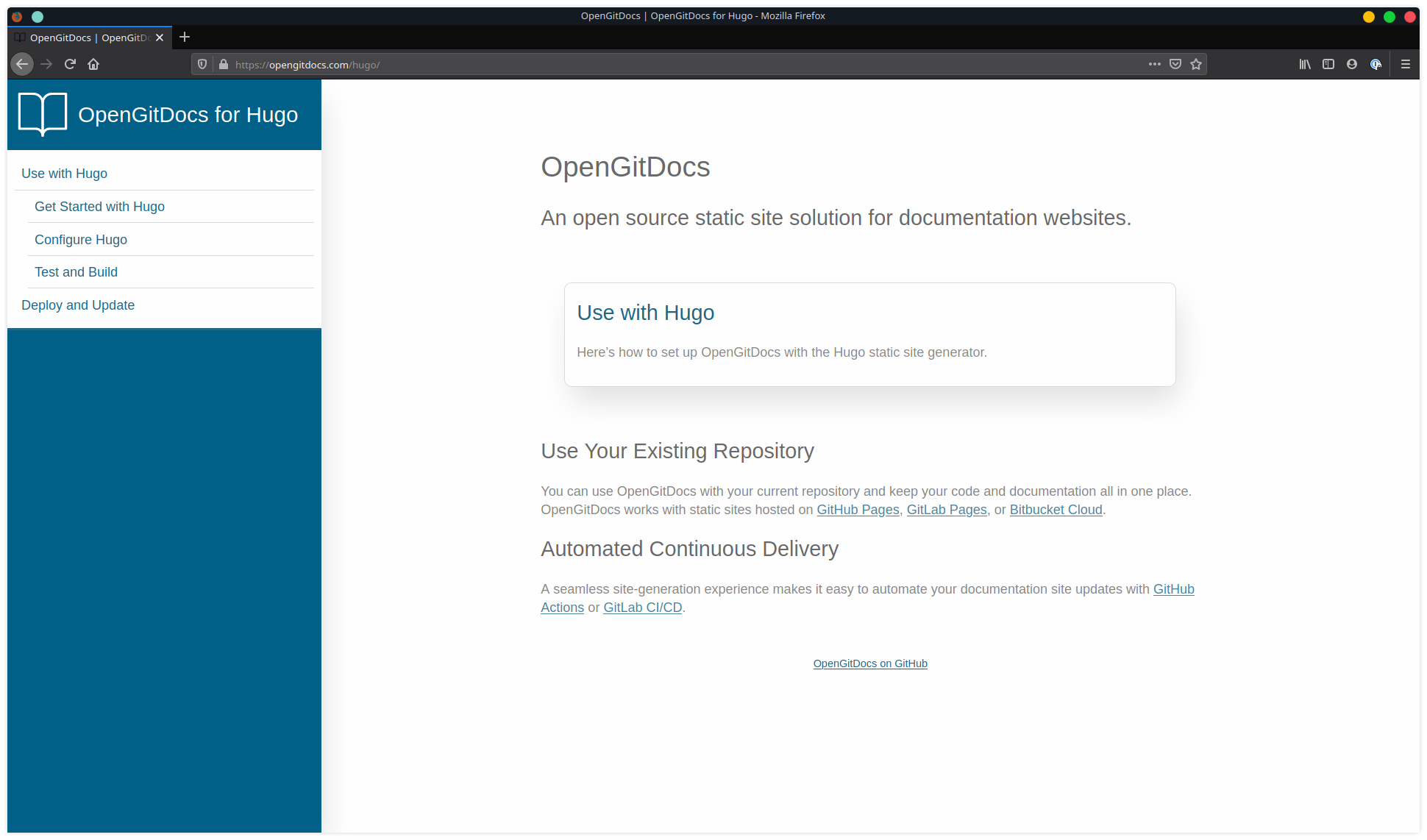

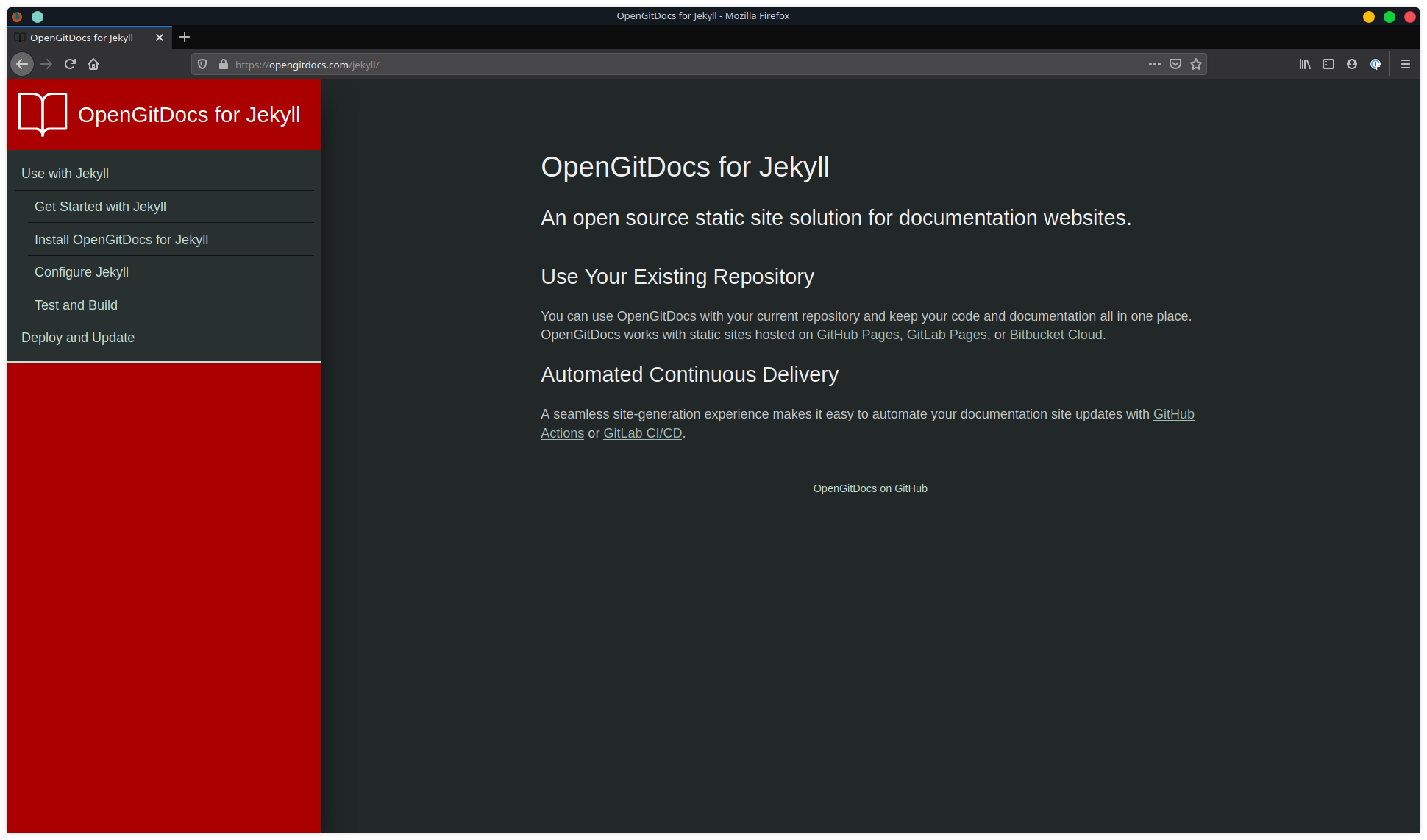

All the substantial differences between these two generators are under the hood. All the same, let’s take a look at the finished themes, in two color variations.

Here’s Hugo:

Here's Jekyll:

Wait who won?

?

Both Hugo and Jekyll have their quirks and conveniences.

From this developer’s perspective, Jekyll is a workable choice for simple sites without complicated organizational needs. If you’re looking to render some one-page posts in an available theme and host with GitHub Pages, Jekyll will get you up and running fairly quickly.

Personally, I use Hugo. I like the organizational capabilities of its Page Bundles, and it’s backed by a dedicated and conscientious team that really seems to strive to facilitate convenience for their users. This is evident in Hugo’s many functions, and handy tricks like Image Processing and Shortcodes. They seem to release new fixes and versions about as often as I make a new cup of coffee - which, depending on your use case, may be fantastic, or annoying.

If you still can’t decide, don’t worry. The OpenGitDocs documentation theme I created is available for both Hugo and Jekyll. Start with one, switch later if you want. That’s the benefit of having options.

Subscribe to my newsletter

Read articles from Victoria Drake directly inside your inbox. Subscribe to the newsletter, and don't miss out.

Written by

Victoria Drake

Victoria Drake

Former digital nomad (54 cities, 11 countries) and principal software engineer at a big org. No stranger to startups. I write about technology, high-output development teams, and living in the age of AI.