The necessary rise of emotional design

freeCodeCamp

freeCodeCamp

By Jordan Harper

One of the best bits of future gazing I’ve read in the last six months was Jason Calacanis’ proposal that Airpods are Apple’s Best Product Since the iPad. You should read it (once you’ve read this, obviously) but to précis: in a world where AI and conversational interfaces can perform tasks as effectively and seamlessly as we currently do with our stubby little fingers and touchscreens, then an Airpod (or similar) is all we’ll actually need to execute most of the functional tasks we use our screens for today.

And that world is not far away.

Google’s Hector Ouilhet gave one of the most interesting talks I saw at SXSW Interactive 2017, The Future of Conversational UI. He envisages a very near future where, rather than simply doing what they’re told, our voice assistants — be they powered by Google, Amazon, Apple or Samsung — are smart enough to learn from the past, intuit our needs and start doing things for us on a regular basis as well as just providing us with information.

“OK Google, I’ve been invited to talk at SXSW again next year.”

“Great, shall I book the same flights and hotel as last year?”

“That’d be great.”

“Perfect, I’ll send you the boarding pass and your reservation details in a minute. I’ll also order you a taxi for when you arrive and book a table at that great BBQ place you enjoyed last year. Sound good?”

Sounds pretty great to me. If this seems like a long way away or far fetched prediction of how quickly these services will evolve, remember Dator’s Second Law:

Any useful idea about the futures should appear to be ridiculous.

Designing for humans

So making functional design smart, seamless and screenless is a huge deal that could transform the way we interact with technology — and the execution of functional design will largely be away from screens and any form of human interaction outside of language and conversation.

At the opposite end of the scale, we have the kind of design that demands human attention and engagement in order to deliver joy and satisfaction, often without a mandated purpose or end result. Or to give it its common name: game design.

Behavioural design specialist Yu-kai Chou gave another of my favourite talks at SXSW 2017, explaining his theory of Actionable Gamification: a detailed framework that can be used to analyse gamification techniques used by anything we humans interact with, be it apps, social networks, games and even marketing campaigns.

Game designers are masters at what Chou calls Human Focused Design, that is, designing experiences to satisfy the human brain. While gamification is too often used as a mechanism to try and make a dull experience more sticky, successful game design starts with the game mechanics that get our neurons firing, not the promise of a particularly tangible end result.

Functional vs emotional design

So in the near future, we’re likely to see the discipline of ‘digital design’ split down the middle: on one hand, computational designers creating personalised, conversational and adaptable functional design frameworks, making our lives easier and less taxing by taking advantage of developments in conversational UI and artificial intelligence.

On the other hand: anything we interact with on a screen or that is designed to capture attention and engagement will need to be designed more like a game or an art installation than a functional user experience.

Art and design

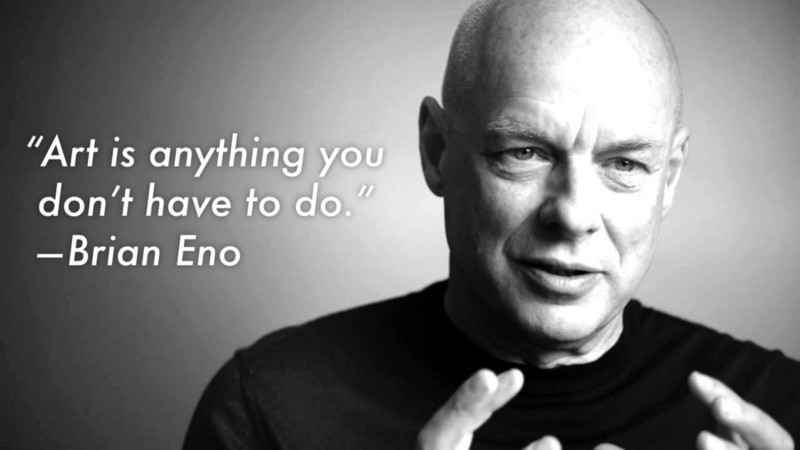

Just as I was finishing writing this piece, I happened to be listening to an episode of Adam Buxton’s brilliant podcast, in which he interviews Brian Eno.

The conversation drifts in a fascinating direction, where we find our heroes talking about why art is important (as opposed to science or more classically ‘productive’ activities).

Eno tells us that he’s come to define art as anything you don’t have to do, and that art can be thought of as any area of our lives where we engage in non-functional stylisation — from symphonies and Cezannes, to cake decoration and funny ways of walking. He also argues that art and these ‘non-functional’ activities serve a valuable purpose for us as a species: we know that children learn primarily through play, it’s how they come to understand the world, and that as we get older, we play through art.

Whether you call it art, applied creativity, gaming or emotional design — creating experiences that satisfy and stimulate the human brain is the most effective way of learning, teaching and — to borrow a phrase from Marie Kondo — sparking joy in our lives.

As conversational interfaces, increasing automation and artificial intelligence combine to help perform our functional needs more seamlessly and efficiently than ever before, designing for humans will become more and more like art.

It’s funny to think that after a decade or more of interactive design drifting towards usability, functional user experience and optimising journeys for speed and simplicity, it may be an artist’s talent for creating emotionally resonant, playful and game-like experiences that could be most important for anything designed for screens in the near future.

Thanks for taking the time to read my rambling thoughts. If you enjoyed it, please recommend, share, hit me up on twitter or respond if you want to keep the conversation going!

Subscribe to my newsletter

Read articles from freeCodeCamp directly inside your inbox. Subscribe to the newsletter, and don't miss out.

Written by

freeCodeCamp

freeCodeCamp

Learn to code. Build projects. Earn certifications—All for free.