Three.js Tutorial - How to Build a Simple Car with Texture in 3D

Hunor Márton Borbély

Hunor Márton Borbély

Putting together a 3D scene in the browser with Three.js is like playing with Legos. We put together some boxes, add lights, define a camera, and Three.js renders the 3D image.

In this tutorial, we're going to put together a minimalistic car from boxes and learn how to map texture onto it.

First, we'll set things up – we'll define the lights, the camera, and the renderer. Then we'll learn how to define geometries and materials to create 3D objects. And finally we are going to code textures with JavaScript and HTML Canvas.

How to Setup the Three.js Project

Three.js is an external library, so first we need to add it to our project. I used NPM to install it to my project then imported it at the beginning of the JavaScript file.

import * as THREE from "three";

const scene = new THREE.Scene();

. . .

First, we need to define the scene. The scene is a container that contains all the 3D objects we want to display along with the lights. We are about to add a car to this scene, but first let's set up the lights, the camera, and the renderer.

How to Set Up the Lights

We'll add two lights to the scene: an ambient light and a directional light. We define both by setting a color and an intensity.

The color is defined as a hex value. In this case we set it to white. The intensity is a number between 0 and 1, and as both of them shine simultaneously we want these values somewhere around 0.5.

. . .

const ambientLight = new THREE.AmbientLight(0xffffff, 0.6);

scene.add(ambientLight);

const directionalLight = new THREE.DirectionalLight(0xffffff, 0.8);

directionalLight.position.set(200, 500, 300);

scene.add(directionalLight);

. . .

The ambient light is shining from every direction, giving a base color for our geometry while the directional light simulates the sun.

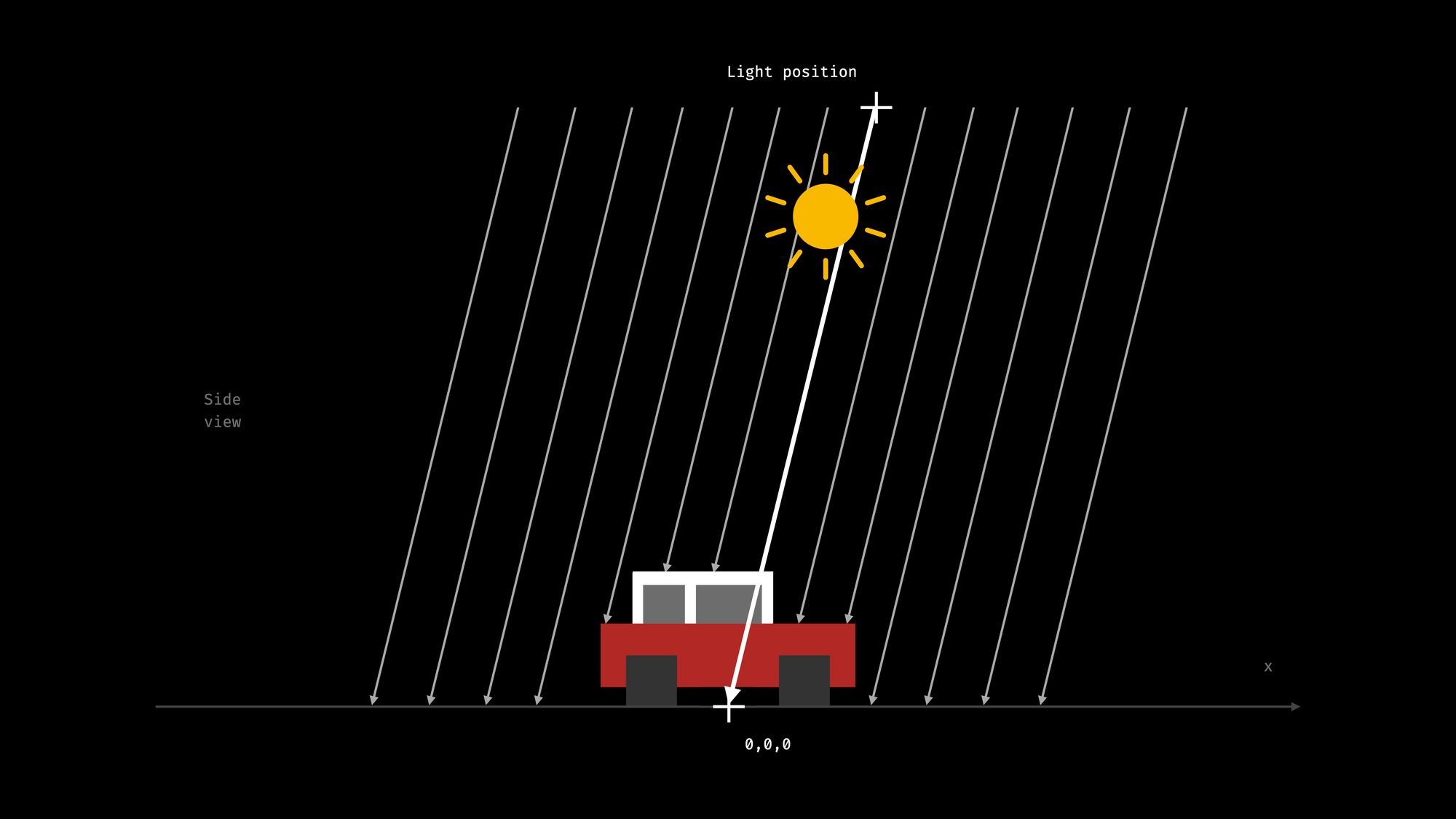

The directional light shines from very far away with parallel light rays. We set a position for this light that defines the direction of these light rays.

This position can be a bit confusing so let me explain. Out of all the parallel rays we define one in particular. This specific light ray will shine from the position we define (200,500,300) to the 0,0,0 coordinate. The rest will be in parallel to it.

As the light rays are in parallel, and they shine from very far away, the exact coordinates don't matter here – rather, their proportions do.

The three position-parameters are the X, Y, and Z coordinates. By default, the Y-axis points upwards, and as it has the highest value (500), that means the top of our car receives the most light. So it will be the brightest.

The other two values define by how much the light is bent along the X and Z axis, that is how much light the front and the side of the car will receive.

How to Set Up the Camera

Next, let's set up the camera that defines how we look at this scene.

There are two options here – perspective cameras and orthographic cameras. Video games mostly use perspective cameras, but we are going to use an orthographic one to have a more minimal, geometric look.

In my previous article, we discussed the differences between the two cameras in more detail. Therefore in this one, we'll only discuss how to set up an orthographic camera.

For the camera, we need to define a view frustum. This is the region in the 3D space that is going to be projected to the screen.

In the case of an orthographic camera, this is a box. The camera projects the 3D objects inside this box toward one of its sides. Because each projection line is in parallel, orthographic cameras don't distort geometries.

. . .

// Setting up camera

const aspectRatio = window.innerWidth / window.innerHeight;

const cameraWidth = 150;

const cameraHeight = cameraWidth / aspectRatio;

const camera = new THREE.OrthographicCamera(

cameraWidth / -2, // left

cameraWidth / 2, // right

cameraHeight / 2, // top

cameraHeight / -2, // bottom

0, // near plane

1000 // far plane

);

camera.position.set(200, 200, 200);

camera.lookAt(0, 10, 0);

. . .

To set up an orthographic camera, we have to define how far each side of the frustum is from the viewpoint. We define that the left side is 75 units away to the left, the right plane is 75 units away to the right, and so on.

Here these units don't represent screen pixels. The size of the rendered image will be defined at the renderer. Here these values have an arbitrary unit that we use in the 3D space. Later on, when defining 3D objects in the 3D space, we are going to use the same units to set their size and position.

Once we define a camera we also need to position it and turn it in a direction. We are moving the camera by 200 units in each dimension, then we set it to look back towards the 0,10,0 coordinate. This is almost at the origin. We look towards a point slightly above the ground, where our car's center will be.

How to Set Up the Renderer

The last piece we need to set up is a renderer that renders the scene according to our camera into our browser. We define a WebGLRenderer like this:

. . .

// Set up renderer

const renderer = new THREE.WebGLRenderer({ antialias: true });

renderer.setSize(window.innerWidth, window.innerHeight);

renderer.render(scene, camera);

document.body.appendChild(renderer.domElement);

Here we also set up the size of the canvas. This is the only place where we set the size in pixels since we're setting how it should appear in the browser. If we want to fill the whole browser window, we pass on the window's size.

And finally, the last line adds this rendered image to our HTML document. It creates an HTML Canvas element to display the rendered image and adds it to the DOM.

How to Build the Car in Three.js

Now let's see how can we can compose a car. First, we will create a car without texture. It is going to be a minimalistic design – we'll just put together four boxes.

How to Add a Box

First, we create a pair of wheels. We will define a gray box that represents both a left and a right wheel. As we never see the car from below, we won't notice that instead of having a separate left and right wheel we only have one big box.

We are going to need a pair of wheels both in the front and at the back of the car, so we can create a reusable function.

. . .

function createWheels() {

const geometry = new THREE.BoxBufferGeometry(12, 12, 33);

const material = new THREE.MeshLambertMaterial({ color: 0x333333 });

const wheel = new THREE.Mesh(geometry, material);

return wheel;

}

. . .

We define the wheel as a mesh. The mesh is a combination of a geometry and a material and it will represent our 3D object.

The geometry defines the shape of the object. In this case, we create a box by settings its dimensions along the X, Y, and Z-axis to be 12, 12, and 33 units.

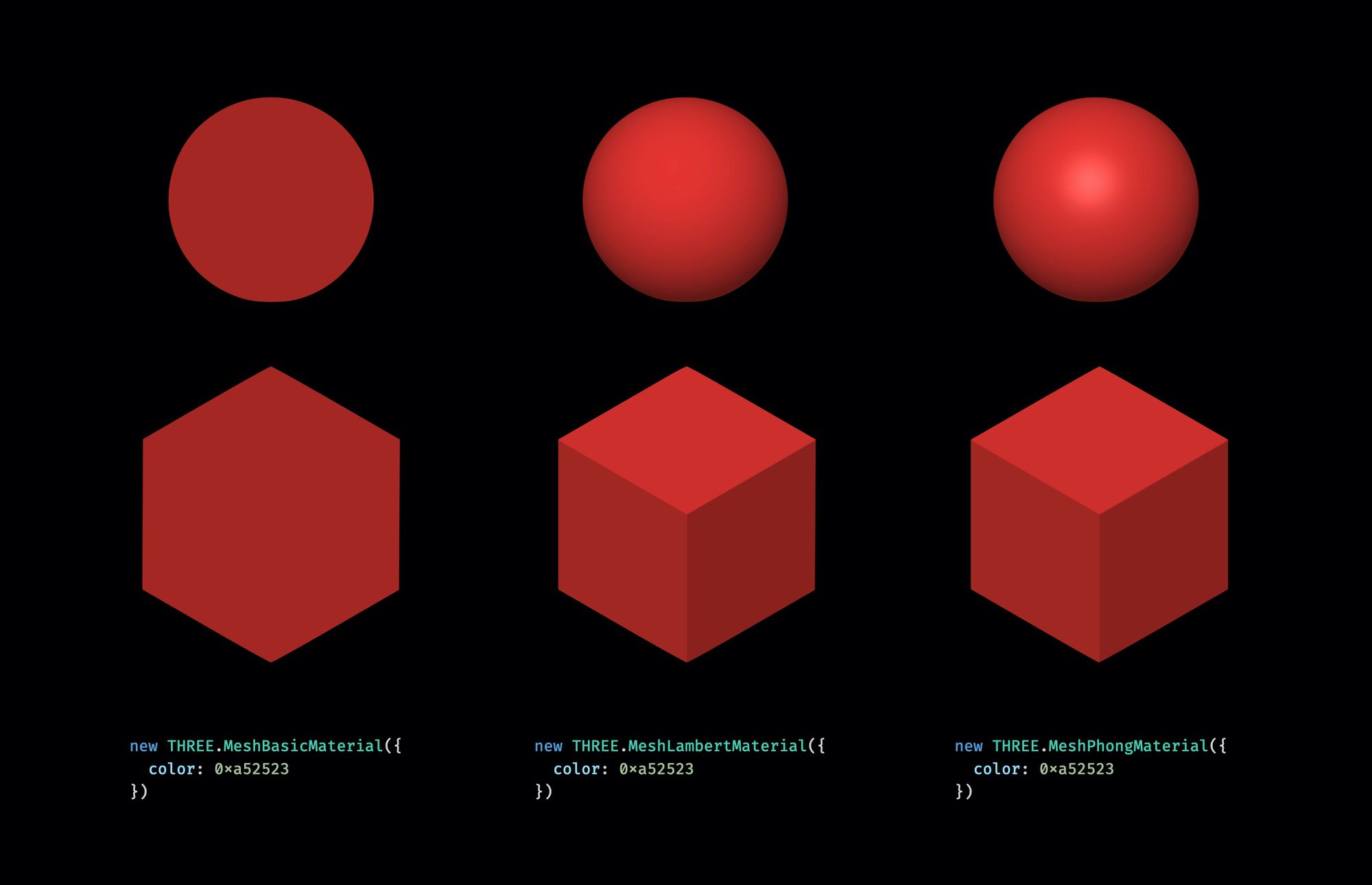

Then we pass on a material that will define the appearance of our mesh. There are different material options. The main difference between them is how they react to light.

In this tutorial, we'll use MeshLambertMaterial. The MeshLambertMaterial calculates the color for each vertex. In the case of drawing a box, that's basically each side.

We can see how that works, as each side of the box has a different shade. We defined a directional light to shine primarily from above, so the top of the box is the brightest.

Some other materials calculate the color, not only for each side but for each pixel within the side. They result in more realistic images for more complex shapes. But for boxes illuminated with directional light, they don't make much of a difference.

How to Build the Rest of the Car

Then in a similar way let's let's create the rest of the car. We define the createCar function that returns a Group. This group is another container like the scene. It can hold Three.js objects. It is convenient because if we want to move around the car, we can simply move around the Group.

. . .

function createCar() {

const car = new THREE.Group();

const backWheel = createWheels();

backWheel.position.y = 6;

backWheel.position.x = -18;

car.add(backWheel);

const frontWheel = createWheels();

frontWheel.position.y = 6;

frontWheel.position.x = 18;

car.add(frontWheel);

const main = new THREE.Mesh(

new THREE.BoxBufferGeometry(60, 15, 30),

new THREE.MeshLambertMaterial({ color: 0x78b14b })

);

main.position.y = 12;

car.add(main);

const cabin = new THREE.Mesh(

new THREE.BoxBufferGeometry(33, 12, 24),

new THREE.MeshLambertMaterial({ color: 0xffffff })

);

cabin.position.x = -6;

cabin.position.y = 25.5;

car.add(cabin);

return car;

}

const car = createCar();

scene.add(car);

renderer.render(scene, camera);

. . .

We generate two pairs of wheels with our function, then define the main part of the car. Then we'll add the top of the cabin as the forth mesh. These are all just boxes with different dimensions and different colors.

By default every geometry will be in the middle, and their centers will be at the 0,0,0 coordinate.

First, we raise them by adjusting their position along the Y-axis. We raise the wheels by half of their height – so instead of sinking in halfway to the ground, they lay on the ground. Then we also adjust the pieces along the X-axis to reach their final position.

We add these pieces to the car group, then add the whole group to the scene. It's important that we add the car to the scene before rendering the image, or we'll need to call rendering again once we've modified the scene.

How to Add Texture to the Car

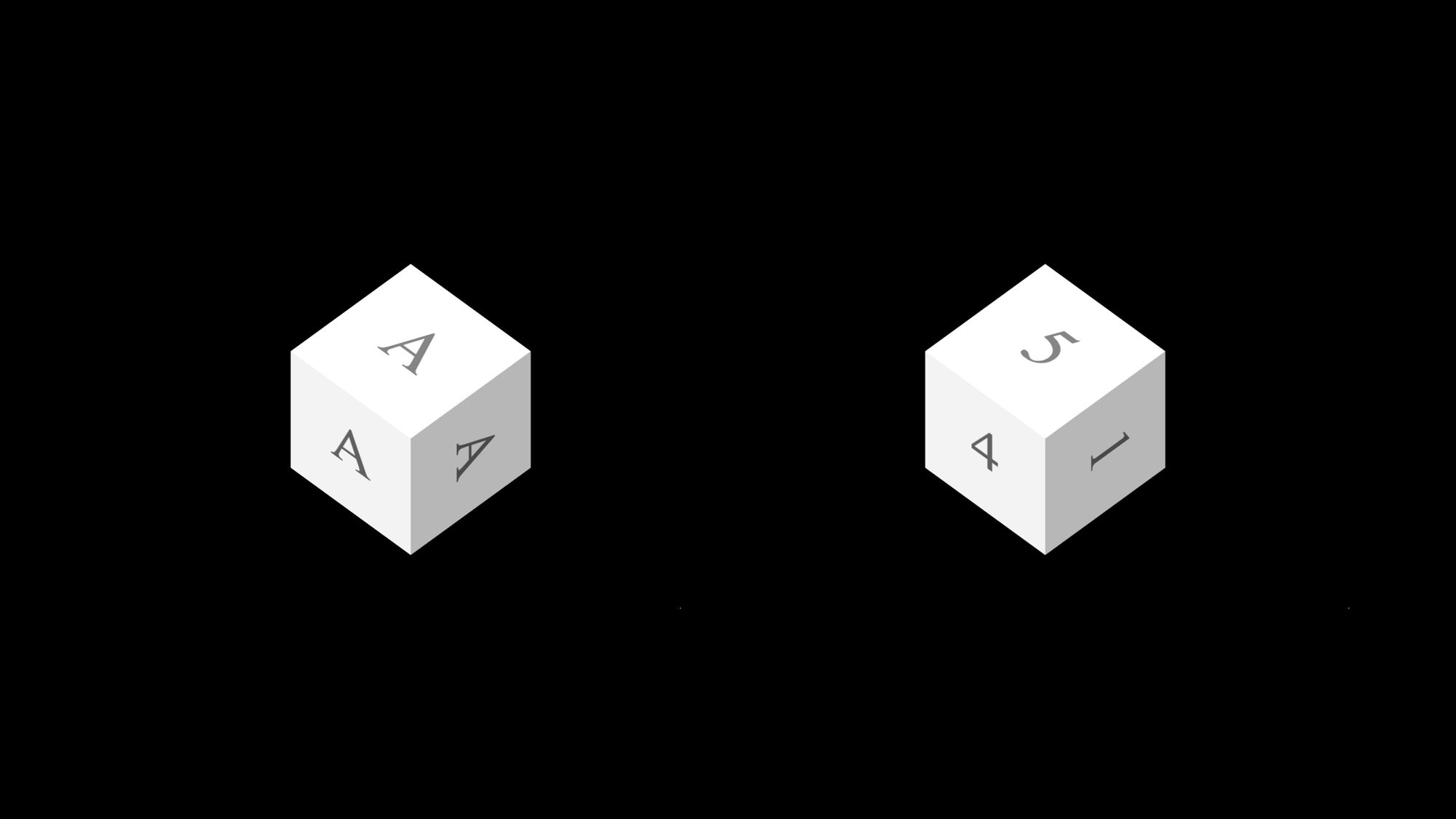

Now that we have our very basic car model, let's add some textures to the cabin. We are going to paint the windows. We'll define a texture for the sides and one for the front and the back of the cabin.

When we set up the appearance of a mesh with a material, setting a color is not the only option. We can also map a texture. We can provide the same texture for every side or we can provide a material for each side in an array.

As a texture, we could use an image. But instead of that, we are going to create textures with JavaScript. We are going to code images with HTML Canvas and JavaScript.

Before we continue, we need to make some distinctions between Three.js and HTML Canvas.

Three.js is a JavaScript library. It uses WebGL under the hood to render 3D objects into an image, and it displays the final result in a canvas element.

HTML Canvas, on the other hand, is an HTML element, just like the div element or the paragraph tag. What makes it special, though, is that we can draw shapes on this element with JavaScript.

This is how Three.js renders the scene in the browser, and this is how we are going to create textures. Let's see how they work.

How to Draw on an HTML Canvas

To draw on a canvas, first we need to create a canvas element. While we create an HTML element, this element will never be part of our HTML structure. On its own, it won't be displayed on the page. Instead, we will turn it into a Three.js texture.

Let's see how can we draw on this canvas. First, we define the width and height of the canvas. The size here doesn't define how big the canvas will appear, it's more like the resolution of the canvas. The texture will be stretched to the side of the box, regardless of its size.

function getCarFrontTexture() {

const canvas = document.createElement("canvas");

canvas.width = 64;

canvas.height = 32;

const context = canvas.getContext("2d");

context.fillStyle = "#ffffff";

context.fillRect(0, 0, 64, 32);

context.fillStyle = "#666666";

context.fillRect(8, 8, 48, 24);

return new THREE.CanvasTexture(canvas);

}

Then we get the 2D drawing context. We can use this context to execute drawing commands.

First, we are going to fill the whole canvas with a white rectangle. To do so, first we set the fill style to be while. Then fill a rectangle by setting its top-left position and its size. When drawing on a canvas, by default the 0,0 coordinate will be at the top-left corner.

Then we fill another rectangle with a gray color. This one starts at the 8,8 coordinate and it doesn't fill the canvas, it only paints the windows.

And that's it – the last line turns the canvas element into a texture and returns it, so we can use it for our car.

function getCarSideTexture() {

const canvas = document.createElement("canvas");

canvas.width = 128;

canvas.height = 32;

const context = canvas.getContext("2d");

context.fillStyle = "#ffffff";

context.fillRect(0, 0, 128, 32);

context.fillStyle = "#666666";

context.fillRect(10, 8, 38, 24);

context.fillRect(58, 8, 60, 24);

return new THREE.CanvasTexture(canvas);

}

In a similar way, we can define the side texture. We create a canvas element again, we get its context, then first fill the whole canvas to have a base color, and then draw the windows as rectangles.

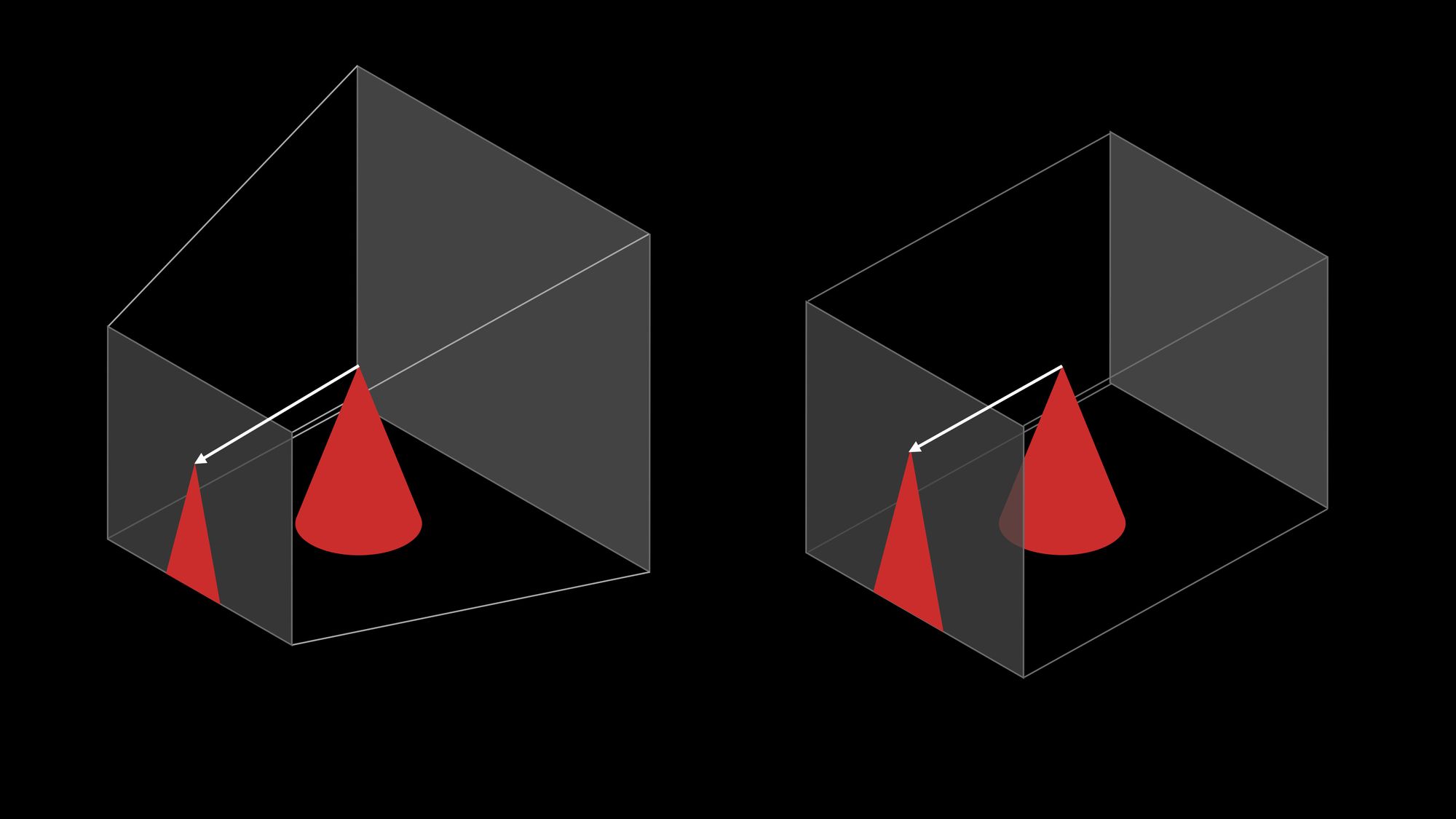

How to Map Textures to a Box

Now let's see how can we use these textures for our car. When we define the mesh for the top of the cabin, instead of setting only one material, we set one for each side. We define an array of six materials. We map textures to the sides of the cabin, while the top and bottom will still have a plain color.

. . .

function createCar() {

const car = new THREE.Group();

const backWheel = createWheels();

backWheel.position.y = 6;

backWheel.position.x = -18;

car.add(backWheel);

const frontWheel = createWheels();

frontWheel.position.y = 6;

frontWheel.position.x = 18;

car.add(frontWheel);

const main = new THREE.Mesh(

new THREE.BoxBufferGeometry(60, 15, 30),

new THREE.MeshLambertMaterial({ color: 0xa52523 })

);

main.position.y = 12;

car.add(main);

const carFrontTexture = getCarFrontTexture();

const carBackTexture = getCarFrontTexture();

const carRightSideTexture = getCarSideTexture();

const carLeftSideTexture = getCarSideTexture();

carLeftSideTexture.center = new THREE.Vector2(0.5, 0.5);

carLeftSideTexture.rotation = Math.PI;

carLeftSideTexture.flipY = false;

const cabin = new THREE.Mesh(new THREE.BoxBufferGeometry(33, 12, 24), [

new THREE.MeshLambertMaterial({ map: carFrontTexture }),

new THREE.MeshLambertMaterial({ map: carBackTexture }),

new THREE.MeshLambertMaterial({ color: 0xffffff }), // top

new THREE.MeshLambertMaterial({ color: 0xffffff }), // bottom

new THREE.MeshLambertMaterial({ map: carRightSideTexture }),

new THREE.MeshLambertMaterial({ map: carLeftSideTexture }),

]);

cabin.position.x = -6;

cabin.position.y = 25.5;

car.add(cabin);

return car;

}

. . .

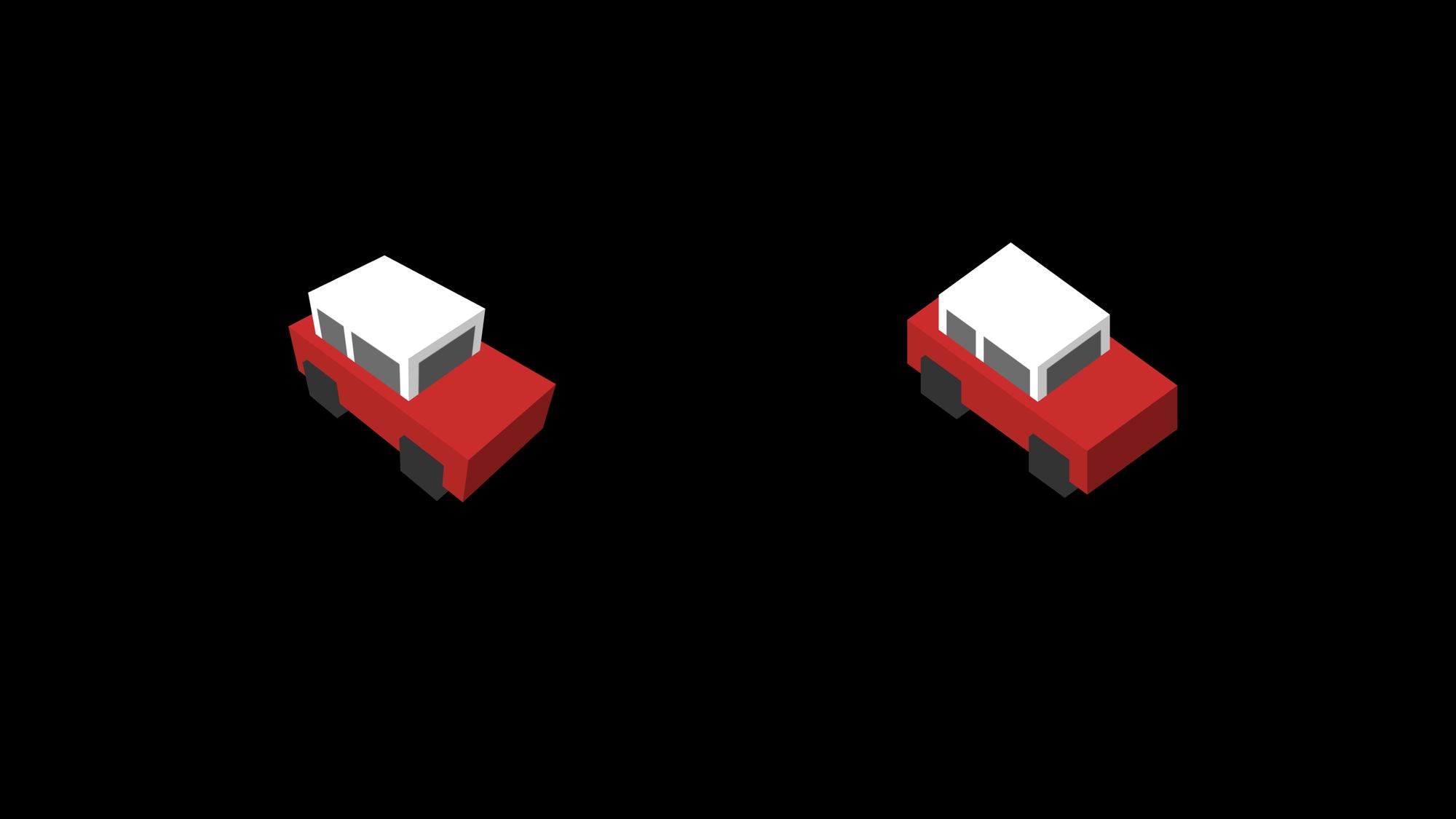

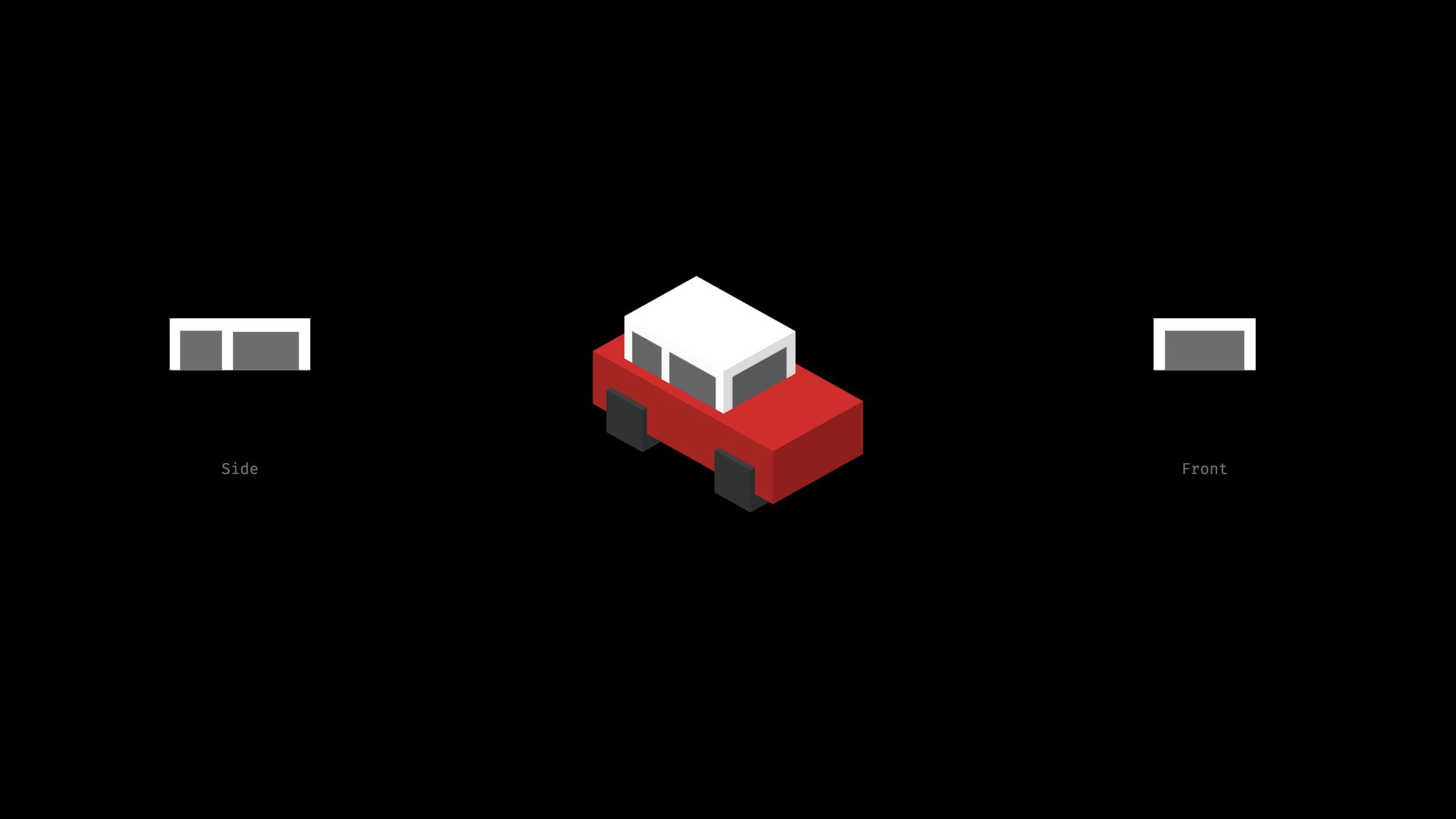

Most of these textures will be mapped correctly without any adjustments. But if we turn the car around then we can see the windows appear in the wrong order on the left side.

Right side and left side before and after fixing the texture

Right side and left side before and after fixing the texture

This is expected as we use the texture for the right side here as well. We can define a separate texture for the left side or we can mirror the right side.

Unfortunately, we can't flip a texture horizontally. We can only flip a texture vertically. We can fix this in 3 steps.

First, we turn the texture around by 180 degrees, which equals PI in radians. Before turning it, though, we have to make sure that the texture is rotated around its center. This is not the default – we have to set that the center of rotation is halfway. We set 0.5 on both axes which basically means 50%. Then finally we flip the texture upside down to have it in the correct position.

Wrap-up

So what did we do here? We created a scene that contains our car and the lights. We built the car from simple boxes.

You might think this is too basic, but if you think about it many mobile games with stylish looks are actually created using boxes. Or just think about Minecraft to see how far you can get by putting together boxes.

Then we created textures with HTML canvas. HTML canvas is capable of much more than what we used here. We can draw different shapes with curves and arcs, but then again sometimes a minimal design is all that we need.

And finally, we defined a camera to establish how we look at this scene, as well as a renderer that renders the final image into the browser.

Next Steps

If you want to play around with the code, you can find the source code on CodePen. And if you want to move forward with this project, then check out my YouTube video on how to turn this into a game.

In this tutorial, we create a traffic run game. After defining the car we draw the race track, we add game logic, event handlers, and animation.

Subscribe to my newsletter

Read articles from Hunor Márton Borbély directly inside your inbox. Subscribe to the newsletter, and don't miss out.

Written by