Academia: Next Generation

Claire Conrad and Lena Muders

Claire Conrad and Lena Muders

As an important step in the competitive world of academia, a PhD thesis is a must when aiming at a professorship. A doctorate is also considered an advantage outside academia: it means that you have proven yourself to be a successful, experienced project manager. By this logic, parents with a PhD must be exceptionally qualified! Keeping a family, its small and big members, healthy, happy and alive challenges our management skills to such an extent that sometimes there are only a few hours left for our second life-filling project: writing a PhD thesis.

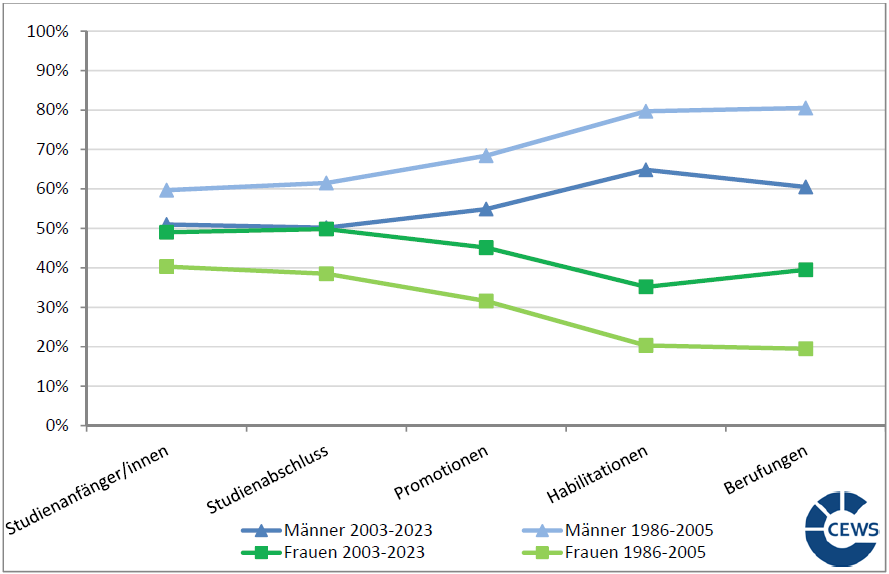

Unfortunately, if you want to compete in academia, you have to complete all stages efficiently. Academia feels especially merciless in Germany due to the Wissenschaftszeitvertragsgesetz: young scholars seem to be interchangeable since they always regrow. The latest report by the Joint Science Center has shown that in Germany, the proportion of women in academia drops with each qualification level after graduation (so-called leaky pipeline). Considering that the timing for both a PhD project and forming a family often coincide (people in their late 20s and 30s), a link between both could be made.

The graph shows the proportion of men (blue shades) and women (green shades) along the qualification and career levels in academia in the last decades. Despite the overall increasing proportion of women at all levels, it continues to drop after graduation. This "leaky pipeline" persists. (https://www.gwk-bonn.de/fileadmin/Redaktion/Dokumente/Papers/Heft_91_Homepage_Stand_07_10_2024.pdf)

Photo by Claire Conrad

At the BCDSS, several PhD candidates either became a mother or father or brought their children with them. We wanted to gain insight into the topic and asked them to share their experiences. What does it mean to manage the two biggest and most identity-forming projects in life at the same time?

1) The experience of becoming/being a parent has changed my academic goals, values and perspective on academia - can you relate to this statement?

“Balancing the demands of the PhD with parenthood inevitably slowed down my academic progress. One of my main priorities was bringing my daughter to Germany and helping her adjust to a new cultural environment. This transition required significant time and attention. Supporting her through this adjustment was essential for her well-being, and, as a parent, it became a crucial goal for me.”

“I feel less stressed about work and more productive at the same time.”

“I have become more self-secure about my values and priorities. My family comes first, the expectations of others are secondary. Academia is still not supportive of young scholars or mothers, so take what you can, give nothing back.”

“My priorities have definitely shifted and I would say that my aspirations within academia have been tempered through becoming a parent. Trying to find my own balance while trying to figure out what example I want to set for my children is hard.”

2) What was/is your biggest academic and/or parental challenge connected to parental leave?

“Trying to organise the administrative side of parental leave while not fully understanding the system was its own challenge. We got there in the end, but that was something… Going back to work after parental leave, it was freeing being able to rediscover the subject that I had loved my whole life, but I felt so immensely guilty for that. Leaving my children was scary, I had to trust that my way was not the only way and that was difficult. When I was pregnant it was easy to know exactly what the right thing to do was to keep my children healthy. Having to trust other people with my hearts, and needing to for my own sanity and wellbeing, was the hardest.”

“Due to my previous experience, I knew that I needed a different kind of stimulation alongside caring for a newborn, so I kept my parental leave short. However, getting back into my topic and work rhythm and keeping it going was and still is a challenge. And then there is the internal voice that either I don’t work enough on my thesis or I don’t spend enough quality time with my kids.”

“Parental leave is only paid for one year but depending on the child’s birthday, there is a gap until daycare can start. The flexibility of home office is an advantage. But working on a PhD cannot be done in little time slots of 30 minutes and many times, this has been the only time I had in a day. And as the more flexible parent work wise, most of the care work remains with me while my partner who works outside academia just sticks to their normal working hours. This is challenging for the relationship.”

“To continue working despite this, but to always be there for my child. You lose touch with the others a bit.”

3) How has the adaptation to becoming/being a parent in academia been going? What has been enriching? What do you do to find a balance?

“As working parents, my partner and I have structured our routines to accommodate both our professional responsibilities and our child's needs. While adapting to new environments can be particularly challenging for children, we have invested time and energy to ensure a smooth transition for her. Maintaining this balance during busy phases, such as dissertation writing, has been demanding but also incredibly rewarding. The greatest satisfaction comes from knowing that despite the pressures of work and research, we are able to provide our child with the quality time and attention she deserves.”

“I definitely feel like I am adapting better now, but it’s taken a while and how ‘well-adapted’ I feel changes on a daily basis. Ensuring some me-time has definitely helped. Once a week I have a video call with some old university friends in the evening that is much needed time to reclaim a small portion of sanity. I don’t actually think a real ‘balance’, has been struck yet…”

“There is no balance so far and the mantra “this is just a phase” helps, but then the phases are very long. It is very enriching to spend time with my child. It helps me to worry less about work related issues and feel less pressure because I know that there is something much more important than work and career in the world.”

“I set deadlines for short tasks I want to achieve this week.”

“I try to focus as much as possible only on the dissertation while at work, and at home basically ignore everything work-related.”

4) Would you say that you have to take back a step from your own research project due to becoming/being a parent?

“I currently see the break after birth as more of an advantage, as it has given me some distance from my project and some things are now clearer to me and I have been able to rethink a lot of things where I was already too stuck in my head before.”

“No, on the contrary, being a single mom to an exceptionally smart 9-year-old has never made me step away from my research; instead, it has constantly motivated and inspired me to persevere, with the goal of making my son proud of his mother.”

“Yes, and I am happy to spend time with my children.”

“I miss the flexibility to travel for workshops, conferences, field research and the like.”

“I feel like after taking a step back, I am finally able to get back into my project, but I don’t feel like I will ever be able to give it the same level of commitment as my priority will always be my children. I feel conflicted, because to secure the future I would like for my children, I need to secure my career. But with limited help and having more than one child, it can be hard to balance and no matter where I place my priorities, I feel guilty for letting the other side down.”

“I can certainly say that I would handle my dissertation in a very different way if I did not have kids. It gives you another type of focus if you cannot put all of your energy in your topic, and I think it helps me not to get too much into all the interesting aspects of my research and get lost in them. So, in a way yes, I take a step back, but I don’t see it as all negative.”

5) Has your perspective on parents in academia shifted?

“Definitely! I have a deeper consideration for the amount of sacrifices that women must make for the sake of their careers; if they have children I feel the conflict of sacrificing your time with career for family and vice versa, and if they don’t, I wonder now how many women sacrificed having a family for the sake of career advancement.”

“Absolutely! They have completely different prerequisites than people without children. Lack of sleep, family-unfriendly conferences, etc.”

“Parenthood has taught me the immense value of mutual support. Balancing both parenting and academic life is demanding, and I have come to realize just how essential it is to have a strong support system. Whether this support comes from my partner, family, or colleagues, it has been crucial in helping me manage both my family commitments and the pressures of my PhD. It serves as a reminder that no one can do it all alone, and the power of shared support is truly invaluable.”

“I often think that single parents in academia either have super powers or are constantly living on the edge. Probably a mix of both, depending on the day.”

“Being a parent while conducting PhD research comes with many challenges, but with strong determination, motivation, inspiration, and a supportive institutional system and colleagues, it is achievable. Now, I realize how much determination it takes to balance parenting and academic commitments. It has shown me that being a parent doesn't limit one's ability to contribute meaningfully to academia; rather, it can be a source of strength and inspiration.”

6) Do you feel that both, people and institutions, are supportive of parents in the BCDSS / in academia? What do you feel is being done well, what else could be helpful?

“I do not feel as though I could have continued doing my PhD after having children if I had been anywhere else. On the whole I think I have been incredibly lucky to have had my children while employed with the BCDSS. Most issues were down to language barriers rather than any intent to inconvenience or due to mental health struggles or administrative bureaucracy. I think that it could have been foreseen a little better just how comfortable and stable a position this is for starting a family and that more structures (family room in office/ family friendly times for workshops etc) could have been in place sooner, and some of these things could still be worked on.”

“In my closest PhD environment and especially from my supervisor, I feel 100% supported. I also felt support from the cluster, especially when it came to the flexibility of parental leave, although I still have the feeling that they would have preferred it if the work had been completed quickly without having a baby first.”

“Support structures do exist for everyday life concerns and people are mostly supportive. But the over all world of academia is not supportive of mothers and children. I think that an academic career is not family-friendly since it demands high flexibility: move around every few years for job positions AND lectures and networking events seem to ALWAYS be in the evening hours when, during pregnancy, I was extremely tired and which now is when my child needs me most. I feel excluded from the academic cultural community. Networking, which is supposed to be essential for a career, is more difficult.”

“Overall, I feel that having a baby during my PhD in the BCDSS I got a lot of support. However, I also realized that this is not normal within academia. From my experience, it often appears that having a family is seen in a very dated light. You are supposed to go to fieldwork on your own, it is made hard to take your family, even just your child, with you. Noticeably, the classes of this winter semester start at the same time than school holidays, so students with schoolchildren have to skip the first classes.”

“Yes, I feel that both people and institutions in the BCDSS are supportive of parents, especially my experience as a single mother has been positive. BCDSS has been very accommodating, for example, supporting my son's participation in summer schools while I conducted archival research in Istanbul and London during the summer holidays. This was incredibly helpful as it allowed me to focus on my work while knowing my son was engaged and cared for. The flexibility offered has been essential in managing my dual roles as a mother and researcher.”

7) Do you have a piece of advice for fellow PhD’s that are currently involved in this topic?

“I’ve learned that the time spent with my child and nurturing a strong parental bond far outweighs any professional or research accomplishments. Being present for my child and fostering that emotional connection is more important than career advancement. Children benefit most from their parents' presence and attention, and nothing can replace the value of being there for them during their formative years.”

“Try to let go of perfectionism in academia and in family matters. In many instances, just doing the bare minimum is enough and it will not matter in the long run. Instead, prioritize and remember what it is that will matter in the years to come.”

“Form a peer group together with at least one other PhD parent. Share your experience and your doubts, suffer, enjoy, reflect and grow together. This helps to put your own mind carousel into perspective.”

“Ask for help. One of my biggest problems has been asking for help because I felt like I needed to earn it which is not true. You deserve to feel capable and no one can manage parenthood and an academic career alone. It doesn’t make you a failure and it doesn’t make you weak.”

“Keep your paperwork.”

Photo by Lena Muders

Doing a PhD is a stressful and rewarding challenge, and so is being a parent. Combining these adventurous undertakings leads to PhD-parents experiencing a similar yet completely different journey toward the title, “Dr.”. We are all in the same storm but sailing different ships through it. The double mental load of planning a thesis, organizing literature, researching on field trips goes hand in hand with organizing medical appointments, managing childcare and family’s quality time. The answers we received from our colleagues clearly support this.

One keyword that emerged from our brief survey is “priority:” the changing of priorities after becoming a parent, having to adapt one’s own priorities, and balancing the needs of many people in personal as well as work life. In many cases, the bond between parent and child(ren) and the time spent with them is the focus. But, at the same time, several underline the push in academic motivation received because of them. The wish to create a strong emotional bond is expressed alongside the wish to set a good example for the children, showing them that raising a loving family is not a decision against seeking professional fulfillment. It can be said that relationships (parent-child, parents, parents-academic environment) are an important aspect of being able to manage and advance on both the personal and professional levels. This underlines how important it is to create and expand support for families in academia so that the choice of a career in academia in combination with healthy family life is/becomes a realistic and normal option.

Reading about our colleague’s experiences and perspectives has been insightful, inspiring and a good mental health exercise. Our heartfelt thanks to you, who have contributed, for being so open! You are doing an amazing job!

Subscribe to my newsletter

Read articles from Claire Conrad and Lena Muders directly inside your inbox. Subscribe to the newsletter, and don't miss out.

Written by