Mimicking a List of Dictionaries with a Linked List in Python

Stephen Odogwu

Stephen Odogwu

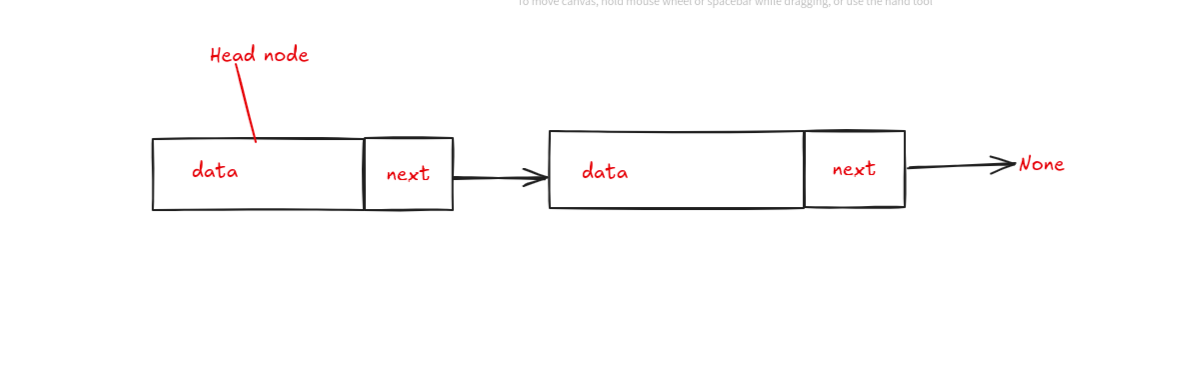

I will be starting this article with my thought process and visualization. An experiment(you can choose to call it that) which opened my eyes to gain more clarity on what linked lists are. This made me stop looking at it as abstract, going by the cliche manner(data and next) which it is always explained.

Thought Process and Visualization

Lately I have started looking at code from a more physical perspective(OOP as it is usually refered to as). However, mine goes beyond classes and attributes; I started writing down steps and algorithms before every while and for-loop. Got tired of jumping into abstractions just for the sake. This led me to try a few more things which further taught me a few more things which I will be sharing in this article.

Three key questions and answers before we delve in deeper:

What makes up a linked list?

What do nodes look like?

What does a linked list look like at the start?

To answer the first; nodes make up a linked list.

For the second question; think of a node in a linked list like a car towing another car. In this scenario, assume both cars contain goods. The second car is attached to the back of the first car with a chain. A node does this in a Linked list by holding data like the goods or passengers in the cars. This data type can be simple like an integer or string or a more complex data structure. At the same time, each car has a connector (chain) linking it to the next car on the road. In a linked list, this is the next attribute which points to the memory address of the next node or the node before(in a doubly linked list). A list is not a linked list without the next attribute.

Each car knows only about the car directly in front or behind it (depending on the type of linked list). The last car has no chain, meaning it points to nothing. In a linked list this is often represented by None.

class Node:

def __init__(self, data):

self.data = data

self.next = None

To answer the third question; the head node starts a linked list just as the first car starts the tow.

class LinkedList:

def __init__(self):

self.head = None

So far, we have looked at the basics of a linked list.We will now be going into the major reason why I wrote this article.

Introduction

Python's built-in data structures, like lists and dictionaries, provide flexible ways to store and manage data. Lists allow us to store ordered sequences, while dictionaries let us pair keys with values for easy access.

In this article, we will explore how to create a dictionary-like linked list by using composition. We will see disparities in memory use between our dictionary-like linked list and a list of dictionaries. We will also see how our node can get an inheritance from dict to make the node instances actual dictionaries. All these in a bid to provide more perspectives for our understanding of a linked list.

Creating Our Linked List

As examined previously, a linked list is made up of nodes. These nodes each have a data segment and a next segment. The data can be simple like a string or integer, or complex.

Simple:

class My_Int:

def __init__(self, data):

self.data=data

self.next=None

The Node class (represented by My_Int) has data and next as attributes.

class My_Int:

def __init__(self, data):

self.data=data

self.next=None

class LinkedList:

def __init__(self):

self.head=None

def insert(self, node):

if self.head==None:

self.head = node

return

last_node = self.head

while(last_node.next):

last_node =last_node.next

last_node.next = node

def traverse(self):

current_node = self.head

while(current_node):

print(current_node.data, end="->")

current_node = current_node.next

print("None")

node1 = My_Int(5)

node2 = My_Int (10)

node3 = My_Int(15)

linked_list = LinkedList()

linked_list.insert(node1)

linked_list.insert(node2)

linked_list.insert(node3)

linked_list.traverse()

Going to be dealing with a complex case in this article:

Complex:

class My_Dict: #dict keys as attributes

def __init__(self, **kwargs):

self.username = kwargs['username']

self.complexion = kwargs['complexion']

self.next = None

The node class (represented by My_Dict) holds multiple attributes: username, complexion, and next. **kwargs as an argument, allows methods to accept any number of keyword arguments without explicitly defining each one.

Each node doesn’t just store a single piece of data but combines multiple pieces (username and complexion) into one, making it more complex than a basic data structure like an integer or a string.

We will now create a My_List class which will manage a linked list of My_Dict instances. It takes a head attribute. This head is usually the first node that initializes a linked list.

class My_List: #manager

def __init__(self):

self.head=None

This class also provides an insert method for adding new node entries at the end. We also create an instance of My_Dict here(which is a node). My_List will act as a container for My_Dict objects in a linked list structure. Each My_Dict instance is connected by a next reference which enables My_List to manage the traversal and insertion of My_Dict instances dynamically. This basically exemplifies composition.

After the creation of a My_Dict instance, we check to make sure the list is not empty by checking for the presence of the head. If the head is not present, it means the list is empty, so we initialize self.head as the new node(which is my_dict). The return then immediately exits the function. No need to execute further.

def insert(self, **kwargs):

my_dict = My_Dict(**kwargs) #instantiate dict

#check if list is empty

if self.head==None:

self.head=my_dict

return

last_dict = self.head

while(last_dict.next):

last_dict = last_dict.next

last_dict.next = my_dict #makes the insertion dynamic

The line after return runs when there was a node previously in the list and we want to insert a new node. We initialize that node last_dict as head and this will be used to find the last node (the end of the list) so that the new node can be appended there. The while loop iterates the list until it reaches the last node. As long as last_dict.next is not equal to None, it moves to the next node by setting last_dict = lastdict.next.

Finally last_dict.next = my_dict appends my_dict to the end of the list completing the insertion. Once we know last_dict.next is None (i.e., we’re at the last node), we attach my_dict there.

We now deal with the traverse function:

def traverse(self):

current_dict = self.head

while(current_dict!=None):

print(f"('username':{current_dict.username}, 'complexion':{current_dict.complexion})", end=" -> ")

current_dict = current_dict.next

print("None")

The traverse function iterates through each node in the linked list and performs an action (in this case, printing) on each node, from the head to the end. The method provides a sequential view of all nodes in the list.

Peep the full code below:

class My_Dict:

#dict keys as attributes

def __init__(self, **kwargs):

self.username = kwargs['username']

self.complexion = kwargs['complexion']

self.next = None

class My_List: #manager

def __init__(self):

self.head=None

def insert(self, **kwargs):

my_dict = My_Dict(**kwargs) #instantiate dict

#check if list is empty

if self.head==None:

self.head=my_dict

return

last_dict = self.head

while(last_dict.next):

last_dict = last_dict.next

last_dict.next = my_dict #makes the insertion dynamic

def traverse(self):

current_dict = self.head

while(current_dict!=None):

print(f"'username':{current_dict.username}, 'complexion':{current_dict.complexion}", end=" -> ")

current_dict = current_dict.next

print("None")

my_list = My_List()

my_list.insert(username = 'Steve', complexion='fair')

my_list.insert(username='Khaled', complexion='dark')

my_list.insert(username='Mike', complexion='fair')

my_list.traverse()

Output

'username':Steve, 'complexion':fair -> 'username':Khaled, 'complexion':dark -> 'username':Mike, 'complexion':fair -> None

Our implementation above can be thought of as a custom linked list of dictionary-like objects, but it’s structured differently from a standard Python typical list of dictionaries. Here are points to note:

My_DictClass: Each instance acts as a dictionary-like object with attributes (username and complexion) and anextpointer, allowing it to be linked to anotherMy_Dictinstance.My_ListClass: This class manages a linked list ofMy_Dictinstances, maintaining the head and providing aninsertmethod to add new entries at the end. Each node is connected to the next via thenextpointer, simulating a linked list structure.

The Algorithm

It is always good to have an algorithm while writing code. This is known as the steps taken. Maybe I should have written them before the code above. But I just wanted to show the difference first between the every day cliche linked list and a more complex type. Without further ado, below are the steps.

Create a class with the attributes of a node structure.

Create another class call it LinkedList(or whatever). Add head as sole attribute. Make head=None.

To create and insert node:

make an instance of

Node.If the list is empty, let node instance be the value of head.

If the list is not empty, set previous node with value as head.

With condition check as; if the next attribute of the previous node is not

None, loop through the list.Finally set next of previous node to point to the new node.

To traverse the list:

Create a temporary node and set head as its start value.

Loop with a condition of if temporary node is not

None.Print data in temporary node.

Move temporary node to next

Finally at end, next is

None, so print None.

Create class instances as required.

Comparison with a List of Dictionaries

We will now compare what we have above with a Python list of dictionaries by looking at some points:

- Structure and Storage:

List of Dictionaries: In Python, a list of dictionaries stores each dictionary as an element in a contiguous list structure, making each dictionary accessible via an index.

list_of_dicts = [

{"username": "Steve", "complexion": "fair"},

{"username": "Khaled", "complexion": "dark"},

{"username": "Mike", "complexion": "fair"},

]

Linked List of Dictionaries: Our code uses a linked list structure, where each node (dictionary-like My_Dict instance) holds a reference to the next node rather than using contiguous memory storage. This is more memory-efficient for large lists if elements frequently change, but it’s slower for access by position.

- Access and Insertion: List of Dictionaries: In a standard Python list, accessing elements by index is O(1) (constant time) because Python lists are arrays under the hood. Adding a new dictionary to the end is usually O(1) but becomes O(n) if resizing is required.

Linked List of Dictionaries: In our linked list, accessing an element requires traversal (O(n) time), as we have to iterate node by node. Inserting at the end is also O(n) because we have to find the last node each time. However, inserting at the start can be O(1) since we can set the new node as the head.

- Memory Usage:

List of Dictionaries: A Python list uses more memory for storing dictionaries in a contiguous block, as each item is stored sequentially. Memory is allocated dynamically for Python lists, sometimes resizing and copying the list when it grows. We can prove this in code using the sys module:

import sys

list_of_dicts = [

{"username": "Steve", "complexion": "fair"},

{"username": "Khaled", "complexion": "dark"},

{"username": "Mike", "complexion": "fair"},

]

# Calculate the memory size of the regular list of dictionaries

list_of_dicts_size = sys.getsizeof(list_of_dicts)

for d in list_of_dicts:

list_of_dicts_size += sys.getsizeof(d)

print("Memory usage of list of dictionaries:", list_of_dicts_size, "bytes")

Output

Memory usage of list of dictionaries: 776 bytes

Linked List of Dictionaries: The linked list uses memory efficiently for each node since it’s only allocating memory as needed. However, it requires extra space for the next reference in each node.

import sys

class My_Dict(): #dict keys as attributes

def __init__(self, **kwargs):

self.username = kwargs['username']

self.complexion = kwargs['complexion']

self.next = None

class My_List: #manager

def __init__(self):

self.head=None

def insert(self, **kwargs):

my_dict = My_Dict(**kwargs) #instantiate dict

#check if list is empty

if self.head==None:

self.head=my_dict

return

last_dict = self.head

while(last_dict.next):

last_dict = last_dict.next

last_dict.next = my_dict #makes the insertion dynamic

#traversal here

def traverse(self):

size = sys.getsizeof(self.head)

current_dict = self.head

while(current_dict!=None):

size += sys.getsizeof(current_dict)

# print(f"'username':{current_dict.username}, 'complexion':{current_dict.complexion}", end=" -> ")

current_dict = current_dict.next

#print("None")

print("Memory usage of linked list with dictionary-like nodes:", size, "bytes")

Output

Memory usage of linked list with dictionary-like nodes: 192 bytes

From the above, we can see the difference in bytes; 776 and 192.

Technically Not Dictionaries

In our code, the My_Dict instances are dictionary-like objects rather than true dictionaries.

Here are some reasons why:

The

nextattribute linksMy_Dictinstances together, making them more like nodes in a linked list than standalone dictionaries. Thisnextattribute is not a feature we'd find in a regular dictionary.Methods and Behavior: Dictionary-like objects (like

My_Dictinstances) can have methods and behaviors that resemble dictionaries but are technically not dictionaries. They lack methods like.keys(),.values(),.items(), and dictionary-specific operations such as hashing. If we wantedMy_Dictobjects to behave more like dictionaries, we could inherit from Python’s built-indictfor implementing methods to give them dictionary functionality. But as it stands, these objects are dictionary-like, since they store data in a key-value style but do not inherit from or behave exactly like Python dictionaries.

Below is a look at how we can inherit from dict class:

from typing import Dict

class My_Dict(dict):

def __init__(self, username, complexion):

super().__init__()

self.username = username

self.complexion = complexion

self['username'] = username

self['complexion'] = complexion

self.next = None # Initialize next to None for linked list functionality

def keys(self):

return super().keys()

class MyList:

def __init__(self):

self.head = None

def insert(self, username, complexion):

new_dict = My_Dict(username, complexion)

if not self.head:

self.head = new_dict

print(new_dict.keys()) # Showing the python dictionary behaviour. Prints keys of head_node

print(new_dict['username']) # Prints username of head node

else:

last_dict = self.head

while last_dict.next:

last_dict = last_dict.next

last_dict.next = new_dict

print(new_dict.keys()) # Showing the python dictionary behaviour. prints keys of other nodes

print(new_dict['username']) # prints username of other nodes

def traverse(self):

# Traversal

current_dict = self.head

while current_dict:

print({key: getattr(current_dict, key) for key in current_dict.keys()}, end=" -> ")

current_dict = getattr(current_dict, 'next', None)

print("None")

my_list = MyList()

my_list.insert('Steve', 'fair')

my_list.insert('Khaled', 'dark')

my_list.insert('Mike', 'fair')

my_list.traverse()

Output

dict_keys(['username', 'complexion'])

Steve

dict_keys(['username', 'complexion'])

Khaled

dict_keys(['username', 'complexion'])

Mike

{'username': 'Steve', 'complexion': 'fair'} -> {'username': 'Khaled', 'complexion': 'dark'} -> {'username': 'Mike', 'complexion': 'fair'} -> None

The first line imports Dict from Python's typing module. This indicates that My_Dict is a specialized dictionary.

from typing import Dict

My_Dict class inherits from dict, meaning it will have the properties of a dictionary but can be customized.

class My_Dict(dict):

Let us take a look at the constructor:

def __init__(self, username, complexion):

super().__init__()

self.username = username

self.complexion = complexion

self['username'] = username

self['complexion'] = complexion

self.next = None # Initialize next to None for linked list functionality

__init__ initializes an instance of My_Dict with username and complexion attributes. super().__init_() calls the parent Dict class constructor. self['username'] = username and self['complexion'] = complexion store username and complexion as dictionary entries, allowing My_Dict instances to be accessed like a dictionary (e.g., new_dict['username']). There is also a next attribute initialized as None, setting up a linked list structure by allowing each My_Dict instance to link to another.

def keys(self):

return super().keys()

The above method overrides the keys method from dict, allowing it to return all keys in My_Dict. Using super().keys() calls the parent keys() method, ensuring standard dictionary behavior.

def insert(self, username, complexion):

new_dict = MyDict(username, complexion)

if not self.head:

self.head = new_dict

print(new_dict.keys()) # Showing the python dictionary behaviour. Prints keys of head_node

print(new_dict['username']) # Prints username of head node

else:

last_dict = self.head

while last_dict.next:

last_dict = last_dict.next

last_dict.next = new_dict

print(new_dict.keys()) # Showing the python dictionary behaviour. prints keys of other nodes

print(new_dict['username']) # prints username of other nodes

In MyList class insert method, we can see how we make the created instance of our dictionary exhibit dictionary behavior. We chain the keys() method to it and we also assess the username key with it. We do this in the if and else blocks. In the if block it prints the keys of the head node and the username. In the else block it prints the keys of the other nodes and the username of the other nodes.

def traverse(self):

current_dict = self.head

while current_dict:

print({key: getattr(current_dict, key) for key in current_dict.keys()}, end=" -> ")

current_dict = getattr(current_dict, 'next', None)

print("None")

In the traverse method above inside the dictionary comprehension:

{key: getattr(current_dict, key) for key in current_dict.keys()}

We construct a dictionary with each key-value pair from current_dict. current_dict = getattr(current_dict, 'next', None) moves to the next node, continuing until current_dict becomes None.

Note: when it comes to memory use, Making our class inherit from

dictmeans more memory use. Unlike the linked list of dictionary-like nodes which we created earlier.

Conclusion

The aim of this article is to provide more perspectives and insight to what linked lists are, beyond what I usually see it explained as. I wasn't being innovative. I was just experimenting with code, trying to provide more insight to those who might be considering it too abstract. However I would like to know from more senior programmers, what the drawbacks could be if used or when used in the past.

Subscribe to my newsletter

Read articles from Stephen Odogwu directly inside your inbox. Subscribe to the newsletter, and don't miss out.

Written by

Stephen Odogwu

Stephen Odogwu

My experiences range from working with frontend, backend and computer networking technologies, a strong knowledge of Linux and even some very good low-level systems understanding like writing network sockets in C. I know I am quite competent and can contribute a great deal as an entry-level or junior developer for a start.