A questionable design choice in Stacks/Clarity

neumo

neumo

Fri 14 March 2025

by 100proof

TL;DR

Most Clarity contracts use a form of authentication similar to Solidity's

tx.originfor sensitive/"owner only" functions. This is a known "bad thing" in the Ethereum community.This authentication method interacts particular poorly with Clarity's (otherwise fantastic) dynamic dispatch mechanism which relies on users passing contracts as function parameters. These contract parameters must implement an interface, known as a trait.

Although Stacks has a novel protection mechanism, called post-conditions, it is inadequate protection against many phishing attacks.

The potential vulnerability has been known about and heavily debated for at least 4 years.

We have identified a popular and heavily used NFT contract that has a very plausible attack path to exploitation.

This exposes an unacceptable number of users to attack, making any "user beware" disclaimer completely insufficient.

We strongly recommend that the Stacks community re-evaluate the security implications of

tx-sender-based authentication and come up with a design that more thoroughly protects users.

Introduction

In October 2024, neumo and I found a vulnerability in the most common implementation of NFT contracts on the Stacks blockchain.

We quickly disclosed the issue to a significant number of affected protocols: all the ones that had bug bounty programs on Immunefi and also a few high profile protocols that didn't. The overwhelming response from the affected protocols, with one notable exception, was "won't fix".

Through this process we learned something. Not only were we not the first to discover the general class of vulnerability, it has been heavily debated with members of the Stacks core development team. Despite heavy debate no significant steps have been taken to mitigate the issue beyond developer education.

So far the debate has been fairly theoretical. But the instance we have found is different. Vast sums of user funds — in NFT-sized chunks — are currently at risk and there is a very plausible phishing/honey-pot attack that could be used to exploit them.

The root cause

Let's get down to business and discuss the root cause.

Most live Clarity contracts do authentication in a particular way. It has become standard practice. An example of the kind of code you might see is:

(asserts! (or (is-eq tx-sender sender) (is-eq contract-caller sender)) ERR_NOT_OWNER)

In this snippet of code sender is a parameter to the function but tx-sender and contract-caller are Clarity built-ins1.

For those who are more familiar with Solidity we can translate the expression:

(or (is-eq tx-sender sender) (is-eq contract-caller sender))

into something more familiar:

tx.origin == sender || msg.sender == sender

So, in the original Clarity code, it is merely checking whether sender is equal to either the tx-sender or contract-caller built-in.

As you might have picked up from our translation into Solidity the problem is with what tx-sender means.

According to the Stacks Documentation tx-sender returns the original sender of the current transaction2. It's just like Solidity's tx.origin. Importantly it is not msg.sender, because it does not return the entity that directly called the contract.

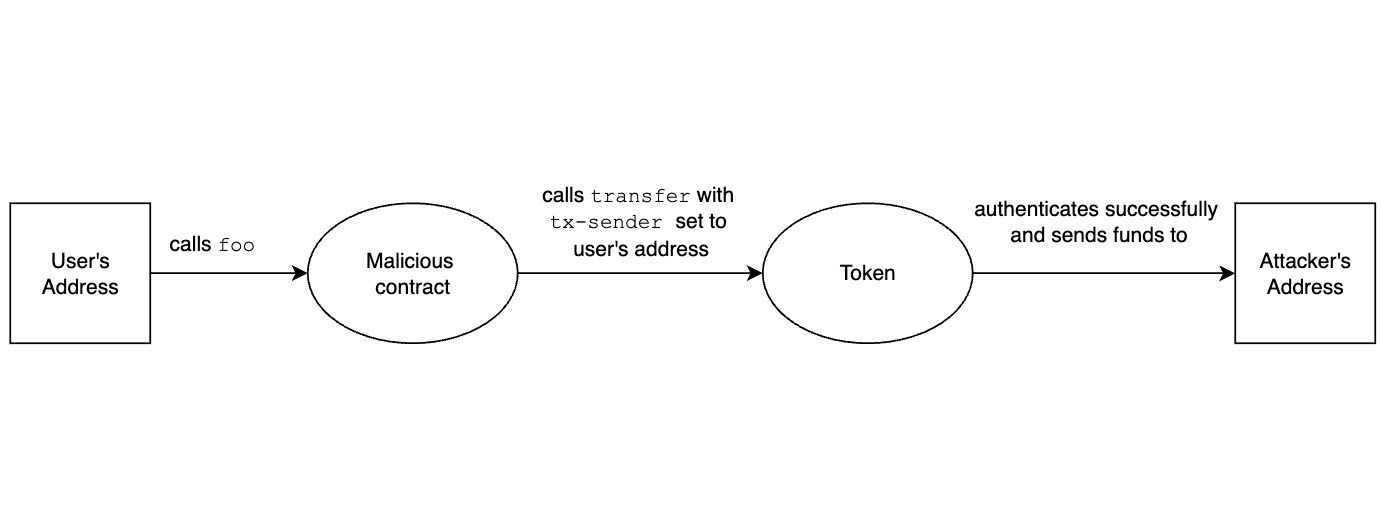

But there is a well-known problem with using the original sender of a transaction to authenticate. Say the sender is somehow tricked into calling a malicious contract M. This contract can now call into any contract that uses tx-sender for authentication and pretend to be the sender!

In Ethereum, and other EVM-based chains, this method is heavily discouraged.

In fact, this exploit vector is even mentioned in the Clarity Book in the section on keywords.

Why is this the recommended method for authentication?

Doing authentication this way might seem like an obviously bad design choice. However, we want to be fair to the core Stacks and Clarity developers. They've actually put some thought into this. As far as we can tell, there are two reasons things are done this way:

Stacks has a novel protection mechanism, called post-conditions that can protect against many attacks.

Users would lose the convenience of performing multiple actions in one transaction via a proxy contract when you use

contract-callerinstead oftx-sender. You can confirm this by examining multiple sources.

But let's discuss post-conditions since they're the strongest argument in favour of the using tx-sender for authentication. We'll try to "steel man" their position before showing that it is inadequate for many kinds of attacks.

Post-conditions

Post-conditions are a novel and powerful mechanism provided by Stacks to protect users. They add an extra level of protection that can protect users regardless of whether the smart contracts users interact with are malicious or contain bugs. Users can add post-conditions to any transaction. If the post-condition is not satisfied the entire transaction aborts. Specifically, they can check for whether:

an amount of STX was sent / not sent

an amount of a fungible token (FT) was sent / not sent

an NFT was sent / not sent

The usual comparison operators such as equality, greater-than, less-than, etc can be used to provide acceptable ranges.

Here are two examples:

A user is interacting with a swap contract and they expect to send 100 STX. Using post-conditions they can ensure that no more and no less is sent.

A user is interacting with contract where they specifically don't expect any of their STX, FTs or NFTs to be sent. They can add post-conditions to ensure none are sent.

You can learn more about post-conditions in the Stacks docs and Hiro Systems docs.

Limitations

However there are some notable limitations to what post-conditions can do.

They can only set conditions on who sends an asset and how much was sent. They don't operate on the final owner. Not only that, they cannot guard against arbitrary state changes in a contract. It is precisely this limitation that means our phishing/honey-pot attack cannot be protected by post-conditions.

Read on for further details.

What we found: vast sums at risk, in NFT-sized chunks.

And now the part of the post you've been waiting for. Just what did we find? And how much is at risk?

In short, we discovered a phishing/honey-pot attack on the most common NFT contract in the Stacks ecosystem. This kind of NFT contract allows users to list their NFTs in a decentralized marketplace. To do this they call a "list" function and must provide a commission contract as a parameter3. Under normal circumstances the commission contract is responsible for paying the seller a small commission when a buyer finally buys the NFT.

This style of contract is used in collections released by Megapont Ape Club, the Stacks Foundation's Mojo and, as far as we can tell, any collection created on Gamma.io. This is by no means a complete list as this style of contract seems to be the de facto standard for NFTs in the Stacks ecosystem.

Here's the exploit. An attacker could list an NFT with a malicious commission contract. Simply by buying this NFT, a victim will have all of their other NFTs listed for sale at a ludicrously low price by the commission contract. The attacker can then just swoop in and buy them, effectively for free.

The value at risk is precisely the sum of the market prices of all the other NFTs the victim owns.

Ready for some more detail?

We'll now go through the basic building blocks of the contract, then give an outline of the attack and, finally, explain why post-conditions cannot prevent this attack.

Building blocks

The source code presented in this section comes from Megapont Ape Club's NFT implementation but the other implementations we listed above are not substantially different, and all suffer from the same vulnerability.

Now we'll list the source code of each important function and provide a short summary.

list-in-ustx

(define-public (list-in-ustx (id uint) (price uint) (comm <commission-trait>))

(let ((listing {price: price, commission: (contract-of comm)}))

(asserts! (is-sender-owner id) ERR-NOT-AUTHORIZED)

(map-set market id listing)

(print (merge listing {a: "list-in-ustx", id: id}))

(ok true)))

sellers call

list-in-ustxto list the NFT for salelist-in-ustxhas 3 parameters: an NFTid, apriceand a commission contractcomm. The contract must implement thecommission-traitinterfacea buyer of the NFT will need to call

buy-in-ustxusing the samecommcontract that the seller passed tolist-in-ustxlist-in-ustxchecks that the caller is authorised to list the NFT using functionis-sender-owner

is-sender-owner

(define-private (is-sender-owner (id uint))

(let ((owner (unwrap! (nft-get-owner? Megapont-Ape-Club id) false)))

(or (is-eq tx-sender owner) (is-eq contract-caller owner))))

is-sender-ownerauthenticates successfully whenever the expression(or (is-eq tx-sender owner) (is-eq contract-caller owner))evaluates totrue. As we'll see below this is a key element of the attack.

buy-in-ustx

(define-public (buy-in-ustx (id uint) (comm <commission-trait>))

(let ((owner (unwrap! (nft-get-owner? Megapont-Ape-Club id) ERR-NOT-FOUND))

(listing (unwrap! (map-get? market id) ERR-LISTING))

(price (get price listing)))

(asserts! (is-eq (contract-of comm) (get commission listing)) ERR-WRONG-COMMISSION)

(try! (stx-transfer? price tx-sender owner))

(try! (contract-call? comm pay id price))

(try! (trnsfr id owner tx-sender))

(map-delete market id)

(print {a: "buy-in-ustx", id: id})

(ok true)))

buy-in-ustxis used to buy an NFT. It takes an NFTidparameter and the same commission contract that the seller used when callinglist-in-ustxThe statement

(asserts! (is-eq (contract-of comm) (get commission listing)) ERR-WRONG-COMMISSION)ensures thatcommis the same one that the seller passed in when they calledlist-in-ustxduring execution the

commcontract is called with the following code.(try! (contract-call? comm pay id price))This calls the

payfunction of thecommcontract passing inidandpriceas parameters.

Outline of the attack

The attack is a classic phishing/honey-pot attack where a malicious actor tricks an unsuspecting victim into interacting with a malicious contract.

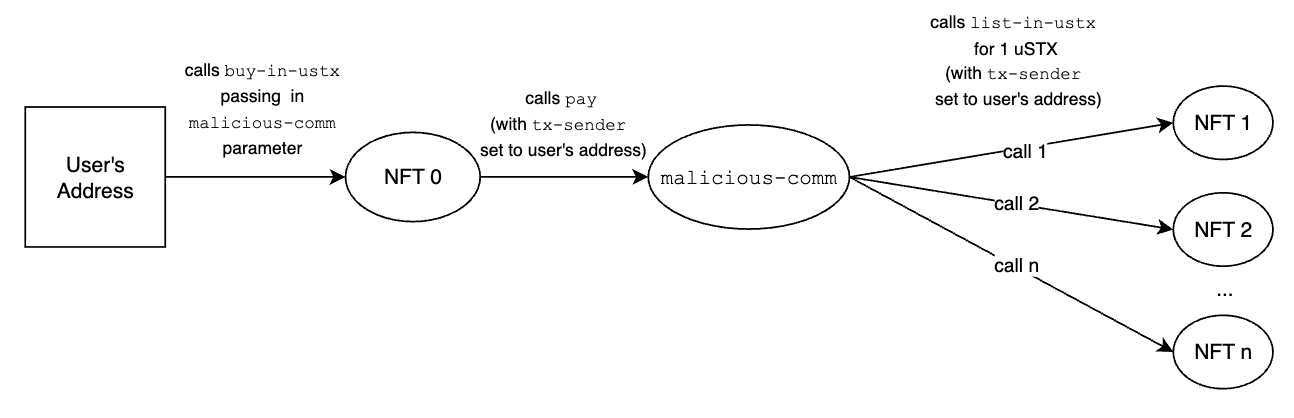

An attacker creates a malicious commission contract:

malicious-comm. The malicious code goes in thepayfunction, which normally just pays a commission to the seller of the NFT.The attacker calls

list-in-ustxpassing in theidof an NFT they own, themalicious-commcontract and apricethat is sufficiently below market price so as to be enticing (but not so low as to set off alarm bells)A victim buys the NFT by calling

buy-in-ustxand passing in the samemalicious-commcontract. We note that this is unlikely to happen for a user interacting directly with the Stacks blockchain. However, it is quite likely to occur to an unsuspecting victim that is using the web app for an NFT marketplace e.g. Gamma.ioDuring execution of

buy-in-ustx, thepayfunction of themalicious-commcontract is called. This is where the magic happens.the code scans for all the NFTS that the victim owns. They don't even have to be part of the same collection as the one they're currently buying. The NFTs merely need to have the same implementation.

for each of these NFTs it will then call

list-in-ustxpassing in itsid, a non-maliciouscommcontract and a ludicrously low salepriceof 1 uSTX (1 micro STX)this call succeeds because of the way

tx-senderworks. The call tolist-in-ustxwill callis-sender-ownerand — sincetx-senderreturns the original caller (i.e. the victim) — it will returntrueand thus the malicious call tolist-in-ustxsucceedsthe execution of

buy-in-ustxfinishes executing and the victim receives the NFT.

However, althought the victim now has a new NFT in their possession, all their other NFTs have been listed for sale at 1 uSTX.

The attacker now buys them all, essentially for free.

Why post-conditions don't help here

It is clear that post-conditions are useless against this attack. This is because post-conditions can only track whether NFTs have been sent or not. The only NFT that was sent in this transaction was the one that the victim was buying, and this was expected!

The others were merely listed for sale. They were not transferred. The only thing that changed was some state in the NFT contract. Unfortunately, post-conditions are of no help here.

Further implications

Gamma.io is still creating collections with this vulnerability

Gamma.io is one of the most popular marketplaces for NFTs in the Stacks ecosystem. Using their platform you can create your own NFT collections. It was also one of the many organisations that we informed of the vulnerability.

Unfortunately, new collections are still being created via this platform that contain the vulnerability. As an experiment we went to the Minting Now page, followed the links to the contract source code and discovered that collections created in just the last 15 days (or less!)4 still have the same vulnerability i.e. that is-sender-owner contains the Clarity expression:

(or (is-eq tx-sender owner) (is-eq contract-caller owner))

More important contracts may be at risk

This is an important point. In this post we have described an attack that causes a user who interacts with a maliciously listed NFT to lose their other NFTs. If only that was the full extent of the problem.

Any contract that uses tx-sender for authentication is at risk.

This is a sobering thought. It is theoretically possible that a protocol owner — using an account that has authority over an important contract — could be tricked into interacting with a malicious NFT and compromise the entire protocol.

Until this kind of vulnerability can be remedied we highly recommend that all important protocol addresses (such as owners, governors, admins, etc) only be used for interacting with protocol contracts and not for anything else.

History

As we said in the introduction, we were not the first to discover this issue. In this section we'll cover the history of this vulnerability in chronological order.

04 Nov 2021 - Treating Traits in Clarity

The earliest mention of tx-sender based authentication we could find was this blog post: Treating Traits in Clarity.

It discusses tx-sender used in conjunction with Clarity's as-contract built-in. Doing this changes tx-sender from the original sender to the contract itself, for the duration of the contract call. As such this blog post actually discusses a slightly different issue than the one covered in this post. However, the final section is worth quoting here:

Second, Clarity requires that traits are provided directly by the user. Traits can't be wrapped or stored. Therefore, the user is in control when using these general contracts. The burden is now on the UI to help users to understand the impact. Apps should inform the users that only vetted contracts can be passed to the general contracts or the apps should warn the user that they are using a potentially malicious contract as a trait. This leads to bigger question about governance. Who can verify contract? Who can blacklist them or who can whitelist them? How can protocol still be permissionless? How can the authenticator support users?

I am looking forward to a healthy discussion about these questions.

16 Nov 2021 - Github repo mijoco-btc/clarity-market issue #6

A short time later a Github issue was published Guarding functions with tx-sender opens up contracts and users for a simple attacks.

It succinctly describes the attack:

Guarding any public function that don't perform any STX/FT/NFT transfer/burn/mint operation with simple

tx-sendercomparison is a potential security hole. It opens up both contracts and contract users for a very simple attack.

It then suggests some mitigations:

Either guard it with

contract-calleror add 1 micro STX transfer to enforce post-conditions.

The idea of adding a 1 uSTX transfer is a little hacky, but it works (for the most part). For normal contract interactions a user is not expecting to be calling a function that requires their authentication. So they can add a post-condition to check that a very specific amount of STX is sent (often 0 STX). If they do accidentally interact with a malicious contract that calls an authentication function the extra 1 uSTX sent causes the post-condition to revert the transaction.

In a follow-up comment the issue poster clarifies this:

Functions that needs extra care are these that can be executed without an post-conditions, and if they get called with malicious intent you can lose control over your contract/protocol/funds. I'm talking about functions like

set-approval-for,set-collection-royalties,update-mint-price,set-edition-cost,transfer-administratorjust to name a few.

Here we can clearly see that the shortcomings of post-conditions were known as far back as November 2021. Not only that, a reasonable, if a little hacky, solution was proposed to protect functions that couldn't be protected with post-conditions:

If you want to allow your users to call these functions via additional contract eg. to set an approval for multiple NFT's in one TX, then I would just add 1 micro STX transfer

Unfortunately, the 1 uSTX transfer protection mechanism has not been implemented in the vulnerable NFT contracts we found.

Further, it won't work in situations where a variable amount of STX sent is expected by the user.

07 Jan 2022 - Setzeus

Two months later, security firm Setzeus provide a detailed post called Clarity, Carefully - tx-sender. They correctly identify the problem...

regardless of how many hops a transaction makes,

tx-senderwill always refer totx-sender— the originator sending the transaction. Now, let’s explore how this persistence can be hijacked for an exploit.

... and then explain a phishing scenario eerily similar to the one we presented.

18 Jul 2024 - BNS-V2 Issue #70

The next post of note is Github repo BNS-V2 Issue #70. It is worth a closer read, if only for the spirited defence of the tx-sender design decision, including an explanation of how tx-sender is useful in a situation where you want to perform multiple operations in one transaction using a proxy contract.

When you use

contract-calleras your security measure, then in case of emergency, when you have to pause/lock/secure multiple contracts, or when it is a multi-step procedure, then you have to submit multiple tx and pray that miners will include them all in a single block.With

tx-sender- you can perform multiple operations within single tx by just deploying a contract that contains all steps that you want to perform.

Clearly tx-sender provides some convenience but is it worth the security risk?

The post also re-iterates the 1 uSTX protection mechanism.

Another thing of note is that BNS actually decided to use contract-caller for authentication based on the discussion! Clearly they saw merit in doing this.

11 Sep 2024 - sBTC Issue #500

The final post we will discuss is Github repo stacks-core/sbtc issue #500. The problem is elegantly summarised as follows:

However, checks against

tx-sendercan be implicitly bypassed once there's a call into a malicious contract. To mitigate this, sBTC relies on Stacks Post-Conditions. These checks, specified outside of contract code, run indeny modeby default, meaning no asset transfers can occur except the ones explicitly allowed. However, there are notable limitations:

You can only track outgoing asset transfers from principals but not incoming asset transfers.

State changes cannot be tracked.

If a contract uses

as-contract, it changestx-senderto its own address. Post-conditions are set once, before the transaction is signed, and cannot be accessed or modified during contract execution. Accordingly, if a contract (e.g.,Foo) callsas-contractand subsequently callssbtc-token:transfer, an attacker could specify a post-condition such as[Foo spends ≥ 0 sBTC]and then drain all sBTC fromFoo.

We are also reminded of the insufficiency of post-conditions.

Avoid using

tx-senderfor any auth purposes altogether as the phishing risk is insufficiently mitigated by Post-Conditions.An EVM-style approval mechanism is recommended instead.

Conclusion

The issues with tx-sender have been known for at least 4 years and are considered a known and accepted risk.

However, the current authentication design is very much "user beware". The responsibility is squarely placed upon the user's shoulders. They must remain eternally vigilant against interacting with any smart contract that could perform a malicious action on their behalf.

We think this view is short sighted and unfair on users many of whom will not have much technical expertise. For the exploit vector we identified there are far too many users who own NFTs to reasonably assert that education alone will prevent them getting phished.

A novel 1 uSTX transfer mechanism has been suggested as a way to protect functions that cannot be protected by post-conditions. However, it has not been implemented in the NFT contracts we discussed, and new collections with this vulnerability are being still being created to this day.

Our motivation to write this post stemmed from our heartfelt belief that the attack vector we discovered is plausible and exposes users to unacceptable risk.

We sincerely hope that this post inspires further discussion and action around the issue.

About us

We found this bug while working together as Pai Mei & Gandalf.

Pai Mei & Gandalf is:

If you'd like to book us for an audit of your Clarity codebase please contact us at

pai_mei_and_gandalf X protonmail Y com

(replacing the X and Y with the obvious symbols)

1 Solidity has many built-ins as well like tx.origin, msg.sender, msg.value etc.

↩︎

2 Unless another Clarity built-in as-contract is used, in which case it will change to be the current contract. ↩︎

3 Clarity does dynamic dispatch via traits. It's a great design for two reasons. First, the fact that traits are type checked at compile time prevents dispatch to arbitrary functions, thus preventing many security vulnerabilities. More importantly — thanks to a prohibition on traits being stored in contract storage — it also neatly prevents re-entrancy attacks. This, combined with a compile time check for dependency loops ensures re-entrancy is impossible. ↩︎

4 When we wrote this the date was 12 February 2025. ↩︎

Subscribe to my newsletter

Read articles from neumo directly inside your inbox. Subscribe to the newsletter, and don't miss out.

Written by