Break into the Black Box of the Enterprise Data Platform - Document Stakeholders.

Christos Georgoulis

Christos Georgoulis

Introduction

In numerous blog posts, industry experts often emphasize "trust" as one of the most important success factors for a data team. And there’s a good reason they bring it up so often. For a data team to deliver value, stakeholders must trust both the team and the data itself. Without this trust, stakeholders may choose to ignore the data altogether.

Many data leaders focus on communication as a way to build trust. However, simply doing a great job technically and relying on communication skills alone might not be enough. To inspire confidence, it’s important that stakeholders don’t just rely on trust in the team itself but also on the transparency of the data infrastructure. Unfortunately, for everyone except the data team, it’s often unclear how the data is produced, where it comes from, and what is being done with it. As a result, data systems can become a "black box" for the organization.

For me, trust should be built organically — a product of the way data teams work, rather than relying on extra efforts to gain personal trust. The ideal situation is not to make people believe in you or your data but to provide a transparent data infrastructure that people can understand and trust on their own. For example, every data product built on top of a platform should have well-documented stakeholders and clear relationships with the data product itself. This approach enhances transparency and builds trust over time. In this post, we will focus on documenting those relationships independently of the tooling you are using.

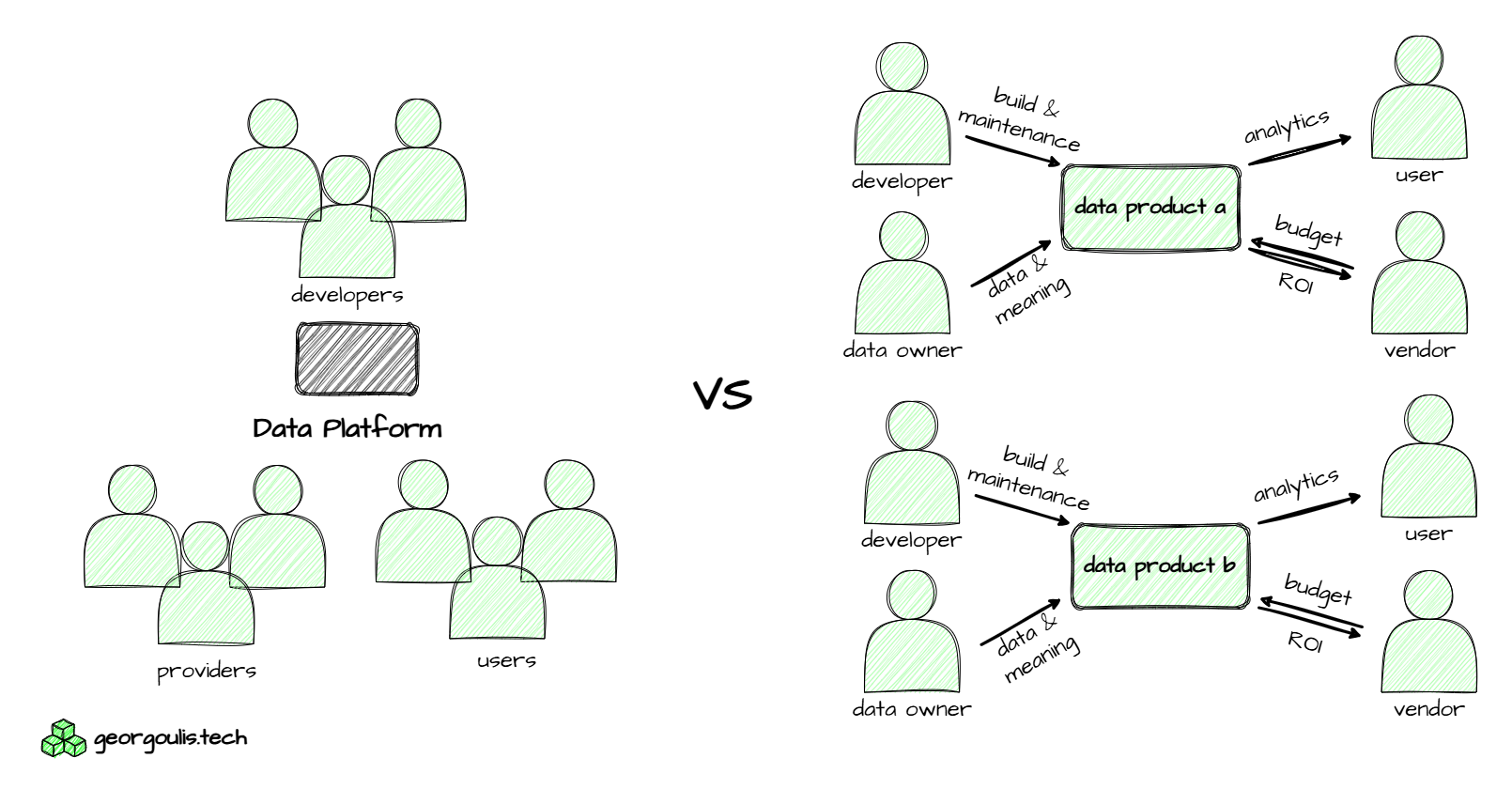

If you’re unfamiliar with the terms "data product" and "data platform," I recommend reading Data Platform vs. Data Product first.

The Roles

A data product stands at the intersection of multiple stakeholders. Some are providers, while others are customers of the data. Documenting these relationships can help make each data product more transparent.

Here are the key roles involved:

User: People who need data and analytics to do their work.

Vendor: The person or group that requested the data product to be built.

Data Owner: The individual or team responsible for the system containing the source data.

Data Entry: The person or process responsible for entering data into the system.

Data Product Developer: The person who builds and maintains the data product.

While these roles are defined in this article, keep in mind that real-life situations can often blur these distinctions. For example, the roles of vendor and user are sometimes the same person or team, or the data entry maybe done automatically from a system rather than a person.

The Example

To illustrate these roles, let’s look at a manufacturing organization as an example. The parties involved in this scenario include the data product developer, the Shop Floor Manager (who uses the data product), the ERP Specialist (who provides access to data), the worker on the production line (who enters the data into the ERP), and the vendor (who oversees the smooth operation of production and expects a positive ROI from the data product investment).

The User:

The user, in this case, could be a Shop Floor Manager. This individual monitors the production progress of orders throughout their day. They can tolerate a 10-minute data latency and require alerts if the production rate risks missing an on-time fulfillment deadline, with at least two hours’ notice to take corrective action.The Data Owner:

The ERP team provides access to the data required by the data product. The data owner must be aligned with the data product team regarding system downtimes and latency. Additionally, the data owner is responsible for providing metadata, defining the business logic, and ensuring that the data is correctly interpreted.The Data Entry:

The worker on the production line inputs data into the ERP system, ensuring that accurate information is recorded. While many systems automate this process (e.g., data pulled directly from machines), in cases where human interaction is involved, it’s critical that data entry steps are well-defined in Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs). This ensures the accurate translation of physical events to digital data.The Vendor:

Finally, the vendor is typically the manufacturing unit's director or a senior stakeholder. The vendor has invested in the data product and expects a return on that investment (ROI). They should have clear visibility into the data product’s costs, benefits, and the value it brings to the organization. They should also be able to answer questions like, “What are the costs of maintaining the data product?” and “How does this data product help improve operational efficiency?”

Conclusion

Trust and transparency are critical to the success of any data product or platform. By clearly defining and documenting the relationships among stakeholders, their expectations from the data product, and their liabilities regarding it, organizations can reduce the "black box" effect, allowing stakeholders to trust the system on their own. Through this transparency, data products become more effective tools for decision-making, ultimately driving value for the business.

While these practices are often emphasized for large projects, it’s equally important to establish routines that ensure consistent tracking and documentation for all data products—big or small. Building these habits into the daily workflow of data teams will ensure that transparency and trust are maintained across all products, leading to a more accountable and efficient data-driven culture within the organization.

Until next one,

Christos Georgoulis

Subscribe to my newsletter

Read articles from Christos Georgoulis directly inside your inbox. Subscribe to the newsletter, and don't miss out.

Written by