My Experience with Studio Ghibli Style AI Art: Ethical Debates in the GPT-4o Era

Jaskaran Singh

Jaskaran SinghHow a viral AI art trend sparked global admiration — and a fierce debate over creativity, consent, and artistic integrity

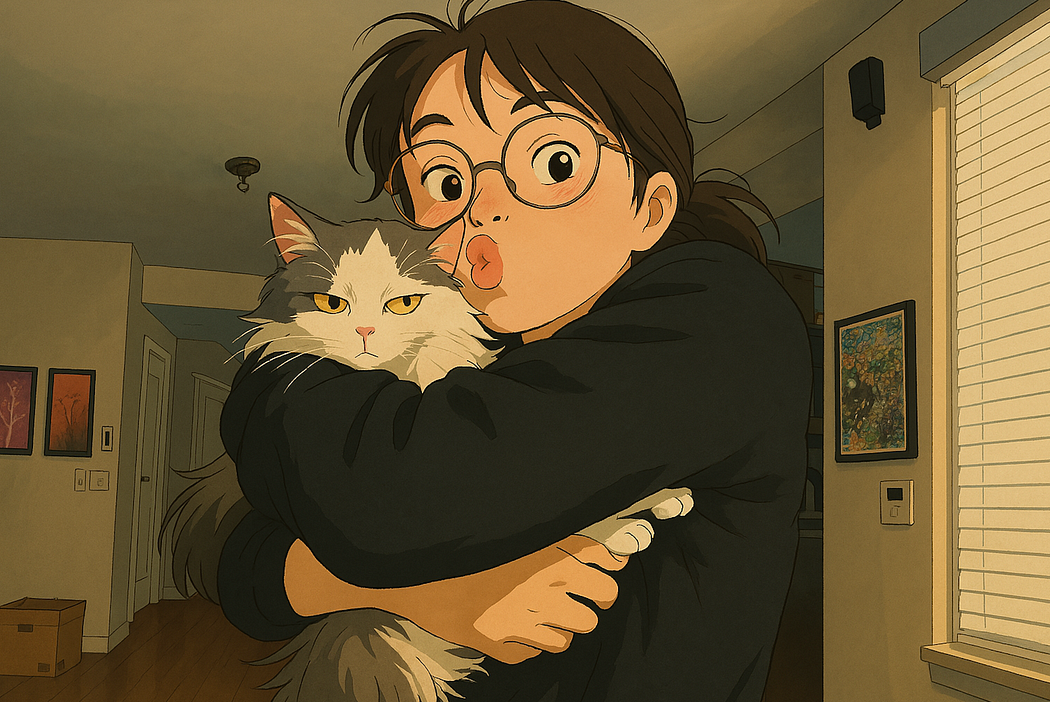

When OpenAI’s GPT-4o model debuted its multimodal capabilities in March 2025, it ushered in a new era of AI-generated art. One of the first viral sensations it sparked was the trend of “Ghiblification” — turning ordinary photos into images evocative of Studio Ghibli’s iconic animation style (Ghibli AI Art Goes Viral). As a lifelong Ghibli fan, I was thrilled to try this myself. Using GPT-4o’s image generator, I transformed photos of me and my cats into whimsical scenes that looked straight out of My Neighbor Totoro. It was emotionally special — almost surreal — to see myself imagined in such a magical hand-drawn world I’ve adored since childhood. Like many others sharing their AI-crafted Ghibli-style portraits online, I felt a rush of nostalgia and joy.

GPT-4o generated image of me and my kitten based on a real life photo in Ghibli style

Yet that joy soon mingled with unease. I began reading about how Hayao Miyazaki, Studio Ghibli’s co-founder, has been an outspoken critic of AI-generated art. In a famous interview, Miyazaki even described a gruesome AI animation as “an insult to life itself”, rejecting the idea of incorporating such technology into his work (Never-Ending Man: Hayao Miyazaki). I also learned of many artists’ concerns that AI tools might be exploiting their hard-won styles without permission. Suddenly, my fun experiment with GPT-4o felt ethically complicated. Was I participating in something that Miyazaki and others would view as a disrespectful misuse of a beloved art style? This piece delves into that very conflict — exploring the ethical and aesthetic debates surrounding AI-generated art in the wake of GPT-4o’s release, and reflecting on whether trends like Ghibli-style AI art are tainting a cherished artistic legacy or celebrating it in new ways.

GPT-4o’s Multimodal Breakthrough in 2025

GPT-4o is OpenAI’s flagship multimodal AI model, first introduced in mid-2024. Unlike earlier models, GPT-4o can understand and generate text, images, and even audio in an integrated way. In March 2025, OpenAI enabled GPT-4o’s native image generation for ChatGPT users, allowing anyone to create pictures by simply describing what they want (Introducing 4o Image Generation). This was a major leap from previous systems (like the standalone DALL-E 3) because GPT-4o could handle complex, conversational image requests with much greater fidelity. Users could upload or take a selfie and ask GPT-4o to redraw it in various styles — from photorealistic edits to stylized illustrations. OpenAI touted how one could refine an image through dialogue, making detailed adjustments on the fly. Early users were amazed by the “insane” quality of the images, noting how accurately GPT-4o translated imaginative prompts into art (‘Insane’: OpenAI introduces GPT-4o native image generation).

Crucially, GPT-4o’s image generation was capable of mimicking distinct art styles with uncanny accuracy. This included not just generic “anime” visuals, but very specific aesthetics like Minecraft block graphics, 8-bit pixel art, or — notably — the gentle watercolor look of Studio Ghibli animations. OpenAI hadn’t disclosed exactly what data was used to train these capabilities, but it’s widely suspected that the model was fed millions of images from the web, including artwork that is likely copyrighted (‘Insane’: OpenAI introduces GPT-4o native image generation). In effect, GPT-4o learned to replicate many art styles from examples — and could now apply those styles to new images at a user’s command. This technical triumph set the stage for excitement as well as controversy. On one hand, it empowered everyday people (not just skilled artists) to create stunning visuals in styles they love. On the other hand, it immediately raised red flags about intellectual property and artistic integrity, since GPT-4o could produce work indistinguishable from a human artist’s style without that artist’s involvement or consent (‘Insane’: OpenAI introduces GPT-4o native image generation).

The Viral Studio Ghibli-Style AI Art Trend

It was a livestreamed demo that truly kickstarted the Studio Ghibli-style AI art trend. During OpenAI’s official presentation, developers took a selfie and asked GPT-4o to turn it into an anime movie frame (OpenAI announces native image generation in ChatGPT and Sora). The result was striking — the photo was instantly “Ghibli-fied,” resembling the gentle, hand-drawn look of a Miyazaki film cell. This demo image went viral on social media, inspiring thousands of people to try the same. Soon my feeds were flooded with Ghibli-esque portraits: friends as wide-eyed characters standing in lush green forests, couples riding the Catbus, even pets rendered as though they were sidekicks in a Hayao Miyazaki adventure. Everyone seemed to be joining the fun, including prominent figures. OpenAI’s CEO Sam Altman even changed his profile picture to a Ghibli-style illustration of himself.

Source: https://x.com/sama

Encouraged by all the buzz, I eagerly uploaded a photo of myself and my two cats into ChatGPT’s new image generator. With a short prompt, I asked GPT-4o to imagine us in a cozy Ghibli-style scene — perhaps lounging in a sunlit meadow like in Kiki’s Delivery Service. The AI delivered: there we were, drawn with soft pastel colors and big expressive eyes, my cat perched on my shoulder as if about to speak. The image genuinely gave me chills of happiness. As someone who grew up watching Spirited Away and Totoro, seeing my own life translated into that art style was like peering into an alternate reality where I could exist in those films’ universe. I wasn’t alone in feeling this way. Many users shared similar AI-crafted images with captions about childhood dreams coming true or how magical it felt to see themselves in Ghibli form. In those moments, the Ghibli AI art trend felt like a heartfelt celebration of the studio’s work — a collective fan tribute enabled by new technology.

GPT-4o generated image of Paquita the meerkat in Ghibli style

However, not everyone viewed it so innocently. Even as Ghibli-style AI art spread across the internet, criticism was mounting. Some artists and fans were uneasy, pointing out potential copyright violations in using Studio Ghibli’s distinct style without permission (OpenAI’s Studio Ghibli-inspired AI art provokes backlash across the internet). After all, these AI-generated images weren’t just “inspired” by Ghibli — they looked almost exactly like stills from actual Ghibli movies. Was that crossing an ethical line? The concern was not abstract: Studio Ghibli’s own Hayao Miyazaki had very publicly denounced AI art. Clips from a 2016 documentary resurfaced, showing Miyazaki’s visceral disgust at an AI-generated animation. “Whoever creates this stuff has no idea what pain is… I am utterly disgusted… I strongly feel that this is an insult to life itself,” he said at the time. Those words hit hard. Here I was delighting in AI-made art imitating Miyazaki’s style, while Miyazaki himself had decried such technology as antithetical to the very life and humanity in art.

Reading Miyazaki’s comments — and seeing many human artists echo similar anger — I started to feel conflicted and even guilty about my own participation in the Ghibli art meme. It dawned on me that what felt like a personal tribute could be seen by others (including the original creator) as a disrespectful appropriation. On social media, debates raged: Were these AI-generated Ghibli images a form of flattery, or a form of theft? Some critics argued that fans were unwittingly trampling on the sanctity of Ghibli’s art. In their view, using an algorithm to copy Miyazaki’s style without his blessing — and flooding the internet with “fake Ghibli” scenes — was a direct affront to the studio’s philosophy of painstaking hand-drawn creativity (Studio Ghibli vs. AI: A Spirited Debate over Artistic Integrity). I found myself caught in the middle. I cherished the Ghibli aesthetic and loved what the AI made for me, yet I couldn’t ignore the voices saying we were tainting something pure. This duality in my experience mirrors the broader conversation around AI art, which is split between awe at what the technology can do and unease about how it’s done.

Ethical Concerns: Copyright, Consent, and Artistic Integrity

Beyond the Ghibli trend, the rise of AI-generated art has triggered intense ethical debates in the art community. At the core is a question of ownership and consent: do artists have rights over the styles and imagery they popularize, and is it wrong for AI to learn from and imitate their work without permission? In the case of GPT-4o, the model’s training data likely included countless images scraped from the internet — including artwork by living artists and studios (‘Insane’: OpenAI introduces GPT-4o native image generation). OpenAI and similar companies have so far been opaque about their data sources, but experts widely assume that copyrighted illustrations and photographs were used to teach these models, since that would explain their mastery of specific styles. This means that when GPT-4o generates a “Studio Ghibli-style” image, it is almost certainly drawing on actual Ghibli frames or concept art that existed in its training set. No permission was asked or given for using those images — a fact that deeply troubles many artists and legal experts (‘Insane’: OpenAI introduces GPT-4o native image generation).

From an artist’s perspective, what GPT-4o does can feel like plagiarism at scale. Imagine spending years developing a unique art style, only to find an AI can reproduce it in seconds at someone else’s behest. As one young illustrator put it, “It’s theft… using the art that someone has spent hours of their life to make in order to spit something out in a matter of seconds.” (AI Is Causing Student Artists to Rethink Their Creative Career Plans). Many artists have voiced similar sentiments, often using hashtags like #NoToAIArt to protest AI image generators’ use of their work without compensation (‘It’s the opposite of art’: why illustrators are furious about AI).

The ethics here are murky: while an AI-generated image may not copy any one specific painting stroke-for-stroke, it mimics the essence of an artist’s labor — effectively reaping the rewards of their creativity without credit. In the case of the Ghibli-style images, Studio Ghibli’s artists spent decades refining their aesthetic. Now an algorithm can mass-produce lookalikes of that aesthetic, and people can enjoy them free — sidestepping the creative process that gave the style meaning.

The controversy extends into the realm of copyright law. Legally, art styles per se can’t be copyrighted, but specific images and characters are. AI companies argue that their models create “entirely new and unique” images that only resemble prior art, and thus do not infringe copyrights (Visual artists fight back). However, artists and even some lawmakers are not convinced. In early 2023, a group of artists (including illustrator Karla Ortiz and cartoonist Sarah Andersen) filed a class-action lawsuit against the makers of popular AI image generators, claiming these tools “violate the rights of millions of artists” by ingesting their works without consent and producing derivative works that compete with the originals (Visual artists fight back). They argue that AI companies are profiting off artists’ backs — building lucrative technology using billions of artworks taken from the web, all while the actual artists see nothing and face potential loss of work opportunities. This lawsuit, and others like Getty Images’ suit against Stable Diffusion, could set important precedents for how AI art is regulated. The outcome may determine whether future AI models will need explicit opt-ins from artists or have certain styles/filtering restricted to respect intellectual property.

Even outside the courtroom, there is a strong cultural pushback against the unfettered use of AI in art. In online forums and communities, some artists have likened AI-generated art to a form of “technological colonization” — where tech companies swoop in and harvest creative content from artists (often without even crediting them in datasets) to build tools that might replace those same artists. In the animation industry, which Studio Ghibli represents, there is fear that studios might use AI to automate background art or in-betweening, potentially displacing jobs. Indeed, the appeal of AI art for businesses is that it’s fast and cheap: why pay an artist for weeks of work when a machine can output a decent image in seconds? There are already examples of companies using AI art for book covers, music videos, and marketing materials in place of human illustrators (AI Is Causing Student Artists to Rethink Their Creative Career Plans).

Each such case raises ethical questions: Is it fair to use AI for this, and what does it do to the value we place on human art?

To be fair, not all artists outright reject AI. Some acknowledge that AI could be a useful tool if implemented with ethical guidelines — for example, if models respected opt-outs or paid licensing fees for training images. But virtually all artists agree on one point: they expect basic respect and consent. As one artist from the Ghibli debate noted, the issue is not an opposition to technology itself, but to “using [their] work like this” without so much as a courtesy notification (Visual artists fight back). The Ghibli-style trend highlighted this concern vividly. Fans like me generated images out of love for Miyazaki’s art, but in doing so we inadvertently disregarded the wishes of the very people who created that art. Hayao Miyazaki has made it clear he does not approve of AI imitating human artistry. So even if the law has yet to catch up, on an ethical level one could argue that we, the users, have a responsibility to honor the artists’ intent. This sentiment has led some to call for stricter regulations or at least guidelines for AI art. Ideas range from content filters (e.g. an AI refusing to produce images in certain trademarked styles) to artist compensation models (perhaps akin to how music streaming pays royalties). While no consensus exists yet, the flurry of discussion itself shows how deeply the GPT-4o-fueled trend has cut into questions of artistic integrity and rights.

An open question

The emergence of GPT-4o’s powerful image generation and the viral Ghibli-style art trend serve as a microcosm of the larger AI art debate. On one hand, this technology showcases astonishing capabilities — it delighted fans (myself included) by making the impossible possible, letting us see ourselves through the lens of our favorite animation studio. On the other hand, it underscores profound ethical and artistic concerns that society has yet to resolve. I set out simply wanting a cute Ghibli drawing of my cats and me, but ended up entangled in questions about innovation vs. infringement, and automation vs. authenticity, that have no easy answers. The experience has left me deeply reflective and admittedly torn.

I can’t deny the wonder I felt seeing my “Ghibli-fied” self — in a sense, it made me appreciate Studio Ghibli’s artistry even more, because it was their style that gave my little AI picture its emotional impact. In that way, one could argue the trend was a heartfelt celebration of Ghibli’s influence, allowing ordinary people to connect with the beauty of Miyazaki’s world in a personal way. Yet, I also can’t shake off the feeling of guilt after hearing voices like Miyazaki’s condemning this very phenomenon. I have to empathize with the artists’ perspective: if something I created were copied by a machine (or by anyone) without my consent, I would likely feel violated and saddened, no matter how flattering others thought it was.

Moving forward, the balance between respecting artists and embracing new creative tools will be crucial. As the Jobaaj article on this trend aptly put it, AI art is a “double-edged sword” — it holds incredible promise, but must be handled with care and respect (Ghibli AI Art Goes Viral). Perhaps with better policies, transparency, and dialogue between technologists and artists, we can find a middle ground where AI art can coexist with traditional art without one undermining the other. For now, I remain ambivalent. The next time a fun AI art trend comes along, I’ll likely think twice about jumping in uncritically. Yet, I’m also hopeful that these conversations are raising awareness and could lead to more ethical innovation in the field. In the end, the debate around AI-generated art isn’t just about technology or law — it’s about our relationship to art itself, and that’s why it strikes such a personal chord with so many of us, myself very much included.

Subscribe to my newsletter

Read articles from Jaskaran Singh directly inside your inbox. Subscribe to the newsletter, and don't miss out.

Written by