What we can say about Google and 2024 Nobel Prizes

Gianluigi Filippelli

Gianluigi Filippelli

I apologize for the delayed publication of this post, but due to the problems with the security certificate that I was writing last week, I preferred to leave this article on hold, so I'm recovering it now.

The second week of october is traditionally dedicated to the official announcements of the Nobel Prizes. The first prize to be awarded is always that for Medicine, followed, in order, by those for Physics and Chemistry, which are the prizes that interest us. In particular, in 2024, the two Nobel Prizes are closely linked by a topic that has often been on everyone's dicsussions: neural networks and artificial intelligence.

So I thought it would be a good idea to dedicate an article to the winners of the Nobel Prizes of 2024, both to tell, to the extent possible, the mathematics of neural networks, and to underline the physical bases that have allowed research in the field of artificial intelligence to obtain an important boost.

First of all I would recap of the Nobel Prize winners:

2024 Nobel Prizes in Physics to John Hopfield and Geoffrey Hinton "for foundational discoveries and inventions that enable machine learning with artificial neural networks"

2024 Nobel Prizes in Chemistry to David Baker "for computational protein design" and Demis Hassabis and John Jumper "for protein structure prediction"

It all started with seven bridges

Our story begins in 1736 when Leonhard Euler solved the famous problem of the seven bridges of Konigsberg, a charming town in Prussia (now Kaliningrad in Russia). The problem posed to him was quite simple: the city was crossed by a river, in the center of which there was (and still is) an island that was connected to the two banks by a system of seven bridges. Was it possible to cross them all without passing more than once on each bridge?

The answer, negative, gave rise to graph theory, which describes a network of nodes connected to each other by one or more paths.

However, graph theory is not very effective in fully describing how a network works, but it is necessary to add a little of mathematics: thus, we arrive at the so-called network theory.

In this way, it is possible to describe each node of the network and how it is connected to the other nodes. From this "local" description we move to a "global" description using the typical mathematics of series: that is, adding each element that describes every node of the network. From a mathematical point of view we would have something like this (where I will not explain the meaning of the symbols for now):

$$\sum_{i=1}^n a_i w_{ij}$$

Thanks to this formalism it is possible to describe a large number of networks, from biological to physical ones.

A chain of spins

A very interesting model in quantum physics that is described with a formalism like previous is the Ising model, which is used to describe a chain, or generalizing a spin lattice. Spin is the quantum number that is associated with the rotation of a particle and can assume two values, +1/2 and -1/2. In its simplest version, the Ising model is described by the following summation, which describes the energy of the system:

$$H = \sum_{i,j} J_{ij} \sigma_i \sigma_j + \sum_j h_j \sigma_j$$

Without going into too much detail, \(\sigma_i\) represent the spins of the various nodes, \(J_{ij}\) the interaction that occurs between the various nodes, \(h_j\) an external magnetic field that acts on the j-th node.

In 1972, the mathematical engineer Shun'ichi Amari proposed a suitably modified Ising model to describe the functioning of a memory.

Amari, born in 1936 in Tokyo, had begun to take an interest in the mathematical aspects of information theory since he was a student, subsequently developing the branch now known as information geometry, a field that applies the techniques of differential geometry to statistics and probability.

Evidently the Japanese mathematician, by virtue of the fact that the Ising model has two values, considered it effective for describing a first initial model for a neural network: in that pioneering phase of research, in fact, there was a tendency to model neurons using two simple states: 0 for the inactive neuron, and 1 for the active neuron.

If we reinterpret the Ising model in terms of modern neural networks, we can associate the spins of the nodes of the original model with the states of the neurons, while the external magnetic field with what are called biases. In this way, the functioning of a neural network is described by the so-called propagation function, which obviously tells us how information propagates within the network itself:

$$p_j = \sum_i o_i w_{ij} + w_{0j}$$

where \(o_i\) is the output returned by the i-th node, \(w_{ij}\) the weights of the network, \(w_{0j}\) are the biases.

With Amari we have one of the first applications of the Ising model to neural networks (in Amari's specific case, an associative memory was being described). His work was followed by William Little in 1974 and the Sherrington–Kirkpatrick model in 1975. And finally the Hopfield model in 1982.

Biology from the point of view of physics

John Hopfield, born on July 15, 1933 in Chicago, Illinois, graduated in physics in 1954 from Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania, and later obtained a PhD, also in physics, in 1958 from Cornell University. He specialized as a theoretical physicist in the field of quantum mechanics. In particular, he studied a particular physical system, known as an exciton, or the bond between an electron and a hole.

Like many Nobel Prize winners before him, he worked at Bell Labs, although only for a couple of years, first dealing with semiconductors, then in continuation with his doctoral thesis, and subsequently with a quantitative model, created together with Robert Shulman, which described the cooperative behavior of hemoglobin. So Hopfield began to shift his field of interest towards biophysics during Bell Labs' years.

The bulk of his work in this field was carried out at Caltech between 1980 and 1987: indeed the paper that earned him the 2024 Nobel Prize in Physics, the one in which he describes what is now known as the Hopfield model, was published in 1982.

Also in that period at Caltech he contributed to the creation of the course The Physics of Computation together with Richard Feynman and Carver Mead. In particular, Hopfield, at Feynman's explicit invitation, took care of the lessons on associative neural networks, described by his 1982 model. Inspired by this experience, Hopfield helped found the doctoral program known as Computation and Neural Systems.

It is interesting at this point to note how it was precisely the work of a biophysicist, interested in understanding the interactions between biological cells (because in practice this was Hopfield's initial inspiration), that was fundamental in giving an important boost to the development of artificial neural networks, popularly known as artificial intelligence.

The next step, however, would come shortly thereafter.

Being discrete is sometimes not useful

Hopfield's model had a small problem, which it carried with it from its initial inspiration, that of the Ising model: being a discrete model.

It was Hopfield himself who realized that his model was able to store very little information, if compared with a proper neural network, and already in 1984 he proposed an extension of his model in which the activation functions of the neurons became continuous. Starting from this extension, the activation functions are interpreted as the probability that a given neuron is active. An idea that, therefore, could only come from a quantum physicist, as Hopfield was by training.

It is at this point in our story that Geoffrey Hinton comes into play, who in a certain sense "pumped" Hopfield's model with a rather particular "amphetamine": Ludwig Boltzmann's statistical thermodynamics.

Hinton, born on December 6, 1947 in the Wimbledon district of London, during his studies combined experimental psychology, a field in which he graduated in 1970, with artificial intelligence, in which he specialized during his PhD in Edinburgh in 1978.

And it is precisely in this field that he developed in 1985, together with David Ackley and Terry Sejnowski, the Boltzmann machine which, once again, descends from the Ising model that describes the interactions between spins. The additions of the three researchers, however, evidently suggested by the physicist Sejnowski, all descend from Boltzmann thermodynamics: for example, the probabilities mentioned above explicitly depend on a term called "temperature".

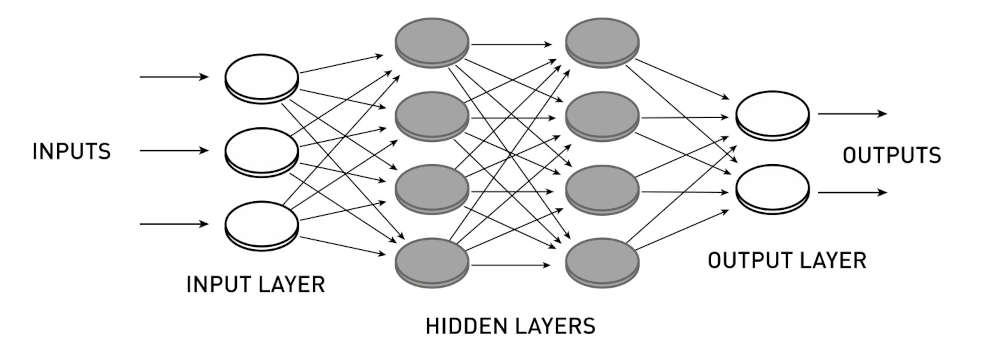

The Boltzmann machine, however, also introduced an idea that has decisively re-founded the approach to neural networks: multilayer networks. The neural network described, in fact, presents a series of hidden networks, in the sense that they are not accessible from the outside. The first hidden network, indeed, send its output to another hidden network and so on, until the last hidden network feeds it to a network that will return the result as output to the outside. The more hidden layers, the deeper its calculations will be, or using a more "colorful" language, the deeper its thinking will be. A bit like the famous Deep Thought!

In any case, Hinton, during his career, also worked for a decade at Google Brain, a division of Google that deals with deep learning techniques, from which he left in a certain sense slamming the door in May 2023: in practice he criticized the direction of development that research on artificial neural networks was taking, which did not take into account any risks associated with this technology.

In a certain sense these concerns echo the statements that Hopfield himself made to the AFP agency after winning the Nobel Prize in Physics:

And as a physicist, I’m very unnerved by something which has no control, something which I don’t understand well enough so that I can understand what are the limits which one could drive that technology.

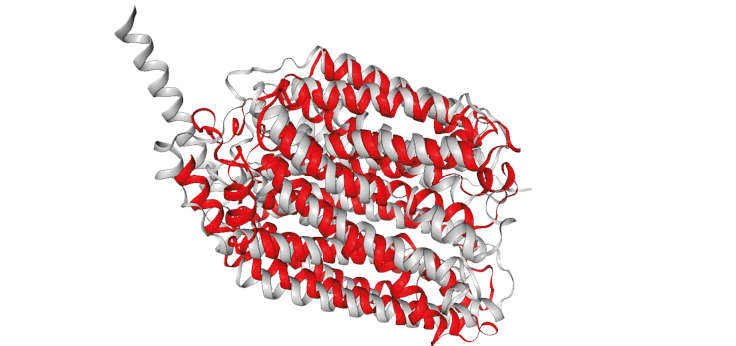

Folding proteins

Demis Hassabis, who together with John Jumper and David Baker won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for computational techniques that allow them to calculate how proteins fold on themselves, is certainly one who has no doubts about the developments of artificial intelligence.

Hassabis is, in a certain sense, a symbol of our multi-ethnic society. He was born on July 27, 1976 to a Greek-Cypriot father and a Chinese-Singaporean mother. At 4 years old he revealed himself to be a chess prodigy, reaching his maximum peak of 2300 elo FIDE points in 1990, effectively retiring from competition in 2019 with a score of 2220.

He studies at Cambridge and is interested in computer science and video games. It is no coincidence that his first jobs were precisely with companies that operate in that field: just as an example, I would mention the two simulation games Republic: The Revolution and Evil Genius.

He then returned to academic studies, obtaining a PhD in neuroscience in 2009 at UCL (University College London). From here he began a journey that led him to found, in 2010, together with Shane Legg and Mustafa Suleyman, the startup Deep Mind, specialized in machine learning, the mathematical and computer techniques for training neural networks. The company was acquired by Google in 2014, and this undoubtedly gave a great boost to Deep Mind, which revolutionized the approach to deep learning with two particularly famous software: AlphaZero and AlphaGo.

In particular, AlphaZero, which we can reductively define as a "chess engine", has become the best in this field thanks to self-training techniques: AlphaZero has played hundreds of thousands of games, completely independently, that is, without having a database of more or less famous games as a starting point. Learning, in the end, from its own mistakes, and also proposing some innovations that have now been introduced even by human chess players.

The same approach was then applied to AlphaGo, a neural network specialized in the Chinese game of Go, and then to AlphaFold, specialized in proteins folding. Which is precisely why Hassabis won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Meanwhile, in the Alpha series, Deep Mind has brought out AlphaGeometry, which aims to solve particularly hard Euclidean geometry problems. Perhaps the next goal is to obtain the Fields Medal, the most coveted mathematical award? In reality, Hassabis is too "old" to get that prize, so he will have to "settle" with the Nobel!

Subscribe to my newsletter

Read articles from Gianluigi Filippelli directly inside your inbox. Subscribe to the newsletter, and don't miss out.

Written by

Gianluigi Filippelli

Gianluigi Filippelli

Master dregree in Physics in scattering theory. PhD in Physics in group theory (ray representation in quantum mechanics). After a master in e-learning I'm Chief Editor / Deputy Editor for EduINAF, INAF magazine about outreach and astronomy education.