Part-time Agile Will Work Against You

Jason Joseph Nathan

Jason Joseph Nathan

LinkedIn rarely fails to entertain.

This week’s showcase: A founder dismisses “clean tickets” as a sign of weak engineers, while another likens standups to overpriced rituals clung to out of habit.

The thing that nagged at me was the fact that each of these posts fixated on a single Agile ritual and then preached about it like gospel.

Everyone thinks it’s Agile because they’re doing their part. Fair enough.

Everyone knows if you skip (or skimp on) even one ceremony, without something solid in its place, that you’re skating on thin ice.

What I didn’t fully realize was that doing it wrong doesn’t just weaken the process, it actively makes things worse.

So that’s what this article is about. We will cover a few things I’ve observed along the way, why it matters, and how (as you’ll soon see) things can spiral into theatre.

Clean Jira Tickets is a Problem

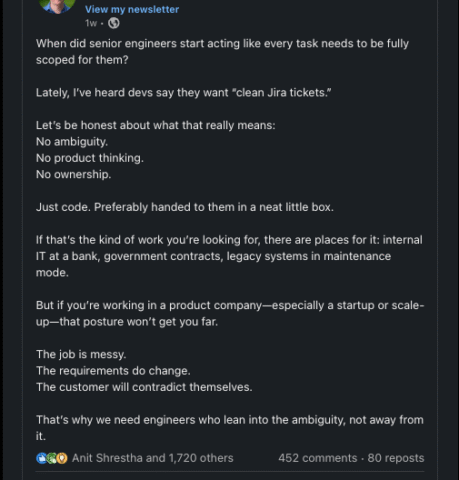

We begin with a founder who argues that the pursuit of “clean tickets” indicates an absence of product thinking.

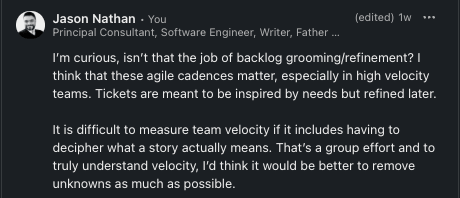

It brought to mind how I’ve managed this exact point of friction before, so I chimed in:

To be fair, not everyone missed the point. A few replies offered grounded and thoughtful responses, like Anna’s:

“When I asked for clean Jira tickets as a senior engineer, I meant a clear explanation of the problem—and the business purpose behind tasks that seem to make no sense at all.”

Precisely. Context is key here. In most cases, it’s the lack of context that leads to prolonged conversations, where team members are simply trying to understand the persona, the intent and/or the use case.

That back-and-forth costs time, and if you’re doing things right, that would get flagged in Retrospective – which is exactly how the definition of a story starts to take shape.

And that’s when clean just means structured.

Further down the thread, Dimitra put it beautifully in metaphor:

“If you ask for ‘food’ and you mean ‘meat’, but I give you ‘salad’, I’ve covered your requirement. But now I have to do it all again.”

This is the cost of ambiguity, and with it, inevitable frustration. This brings me back to my original point about velocity. What does it really mean?

Let’s unpack that.

The Mirage of Velocity

Velocity only becomes meaningful once a team has experienced Agile functioning as a complete, closed loop:

A need is clarified, refined, prioritized, built, delivered, and reflected on – end to end.

This is not an easy thing to accomplish, and many teams never actually get here – at least not in a quantifiable, measurable way.

Why? Because this takes time. It doesn’t happen in a single sprint; in most cases, it can’t.

Those early sprints are often riddled with ambiguity, but more than that, the team is still learning how to work with each other, and with everyone else involved in the product cycle.

It only ever becomes measurable when you remove as many dynamic elements from the process as you can.

Realistically, velocity is constantly distorted by forces that have nothing to do with productivity:

Team members leave mid-sprint and new hires spend weeks ramping up.

Bugs surface (or resurface) in production, demanding emergency fixes mid-sprint.

Requirements arrive late, resolved mid-sprint, while the story was already being worked on.

Work is now estimated before ambiguity is addressed, so the numbers start to spiral, ballooning tickets and planning inevitably loses precision.

Sometimes, that means that a sprint valued at 45 story points was actually worth 23 points after clarification.

This is dangerous, 45 becomes the new gold standard.

Some teams refine after completing the task, but it should’ve been solved before the sprint began.

Eventually, velocity becomes less about a measure of delivery and more a story you’d tell yourself to feel in control.

What follows is predictable:

Ceremonies are questioned and the value of grooming, retros, even stand-up is downgraded.

The undercurrent of impatience silently brews.

“We’ll figure it out as we go.”

“No need to over-process.”

“Let’s just build.”

The worst part about it is that it looks like pragmatism and you start to convince yourself that it is efficient.

More often than not, these are symptoms of burnout and the unravelling of a systemic failure in the process.

Which brings us to the second post, where Agile gets audited, albeit, somewhat angrily.

The Cost of Clarifying

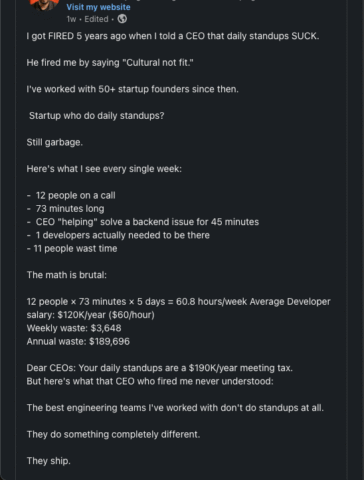

If clean tickets sparked moral panic, the daily standup got hit with a valuation.

(For brevity, this is an excerpt. The full post included a follow-up claim about high-performing teams avoiding standups entirely.)

73 mins? I… I am lost for words here.

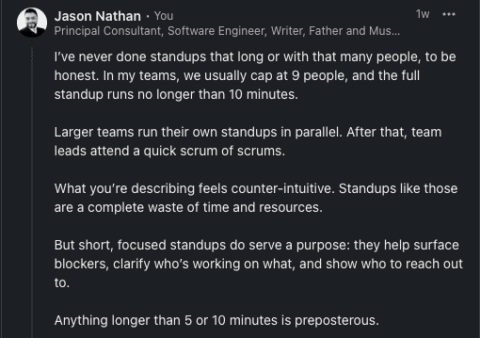

So how can the total duration of a standup, even if participants number at 12, stop at 5 or 10 minutes?

You take it offline.

Standup needs 3 things from each participant:

What you did yesterday: What you started, completed or got stuck with.

What you’re doing today: What would your perfectly productive day is going to look like.

Any impediments?: You state what, possibly who you need help with or from, but you never discuss it.

That last bit is critical because that is exactly what offline means. Standup works marvelously when you quickly remove blockers by having conversations with relevant people before your day begins.

Thatideal dayisthefocus.

Otherwise, you’re making it clear you can’t proceed with clear reasons why.

Perhaps the person you need help from isn’t around or is busy.

That’s why standup insists everyone is present.

Perhaps the requirements are ambiguous.

That’s exactly what Backlog Refinement is for and it’s something to note for Retrospective.

Either way, that transparency is context everyone needs. It’s indispensable.

Abusing it is just sacrilegious.

The Real Cost is Disconnection

There’s a psychological side to Agile that’s massively underrated. But it’s there and it matters more than most people realize.

Standup gives you trickled moments of pride when you report a completed task – and those small daily wins matter because they compound validation over time.

It’s also a platform where you’re allowed to bother the right people for the right reasons.

If you get told that what you thought was important – actually isn’t – that’s useful too.

The clarity you get in Backlog Refinement builds confidence. You know what you’re doing and why. That kind of confidence is exactly what turns someone into the “senior dev” that earlier post so casually threw under the bus.

Retrospectives matter for different reasons. They give you the opportunity to be heard and help you understand what can and can’t be worked on. In either case, that’s a critical pressure release valve every sprint cycle.

That’s what ownership looks like.

It’s the clarity to contribute with purpose.

Because it’s yours.

When Agile Aligns

I’ll end with a short story about something you can’t really explain well in a résumé, but still stands as one of the greatest personal highlights of my career.

I once conducted a Scrum Poker session with developers, loan specialists, program managers, and insurance folks, all working on a complex marketplace project for a bank.

And the coolest thing happened: Every single one of them voted the same number for story points. Over and over. Story after story.

No one said anything and I don’t think they noticed. But for me, it was one of the biggest (yet quietest) moments of alignment I’d ever experienced.

Why?

Because it worked so well, so seamlessly, they didn’t even realize what they were doing perfectly.

That’s the real win.

Quietly, flawlessly aligned.

Back in the day, apps like Kazaa and LimeWire made things feel easy. You searched, you clicked, and the download started (eventually).

There was a kind of thrill to it, even though it was very likely the file turned out to be mislabeled or corrupted.

These CLI tools might not have the glossy buttons or cartoonish logos, but for developers, tinkerers, and anyone who lives in the terminal, they’ve become indispensable. They’re faster and definitely more flexible.

In many ways, they’re more reliable than anything we had back then.

Subscribe to my newsletter

Read articles from Jason Joseph Nathan directly inside your inbox. Subscribe to the newsletter, and don't miss out.

Written by

Jason Joseph Nathan

Jason Joseph Nathan

Yo! I’m J, writer, builder, and your resident geek at Geekist. I’ve spent the last 20 years engineering high-performance software, leading cross-continental teams, and crafting products that don’t just work — they sing. JavaScript, TypeScript, Rust, WordPress, static sites — you name it, I’ve broken and rebuilt it better. Geekist is my playground for all things code, content, and clever hacks. Here, I share deeply technical guides, dev tools, publishing workflows, and creative takes on the developer journey. Expect tutorials with teeth, pipelines with punch, and the occasional spicy metaphor. When I’m not shipping code or shipping books, I’m mentoring devs, remixing beats, and laughing with my daughters and partner-in-chaos, Simo. Welcome to the smarter, stranger side of software.